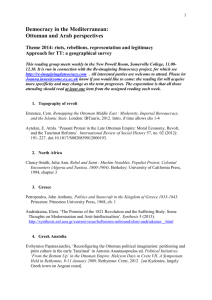

OSMANLI ARAŞTIRMALARI

advertisement