Learning as Work: Teaching and Learning Processes in Contemporary Work Organisations

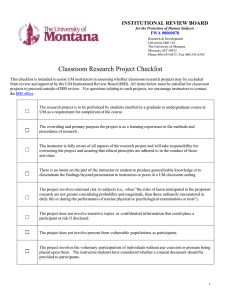

advertisement