Document 12346963

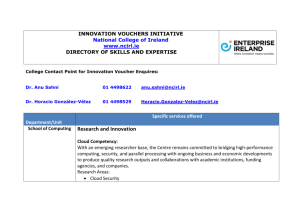

advertisement