Document 12316649

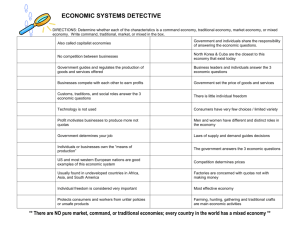

advertisement