WORKING PAPER SERIES Centre for Competitive Advantage in the Global Economy

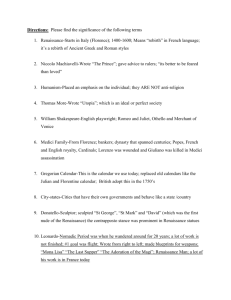

advertisement