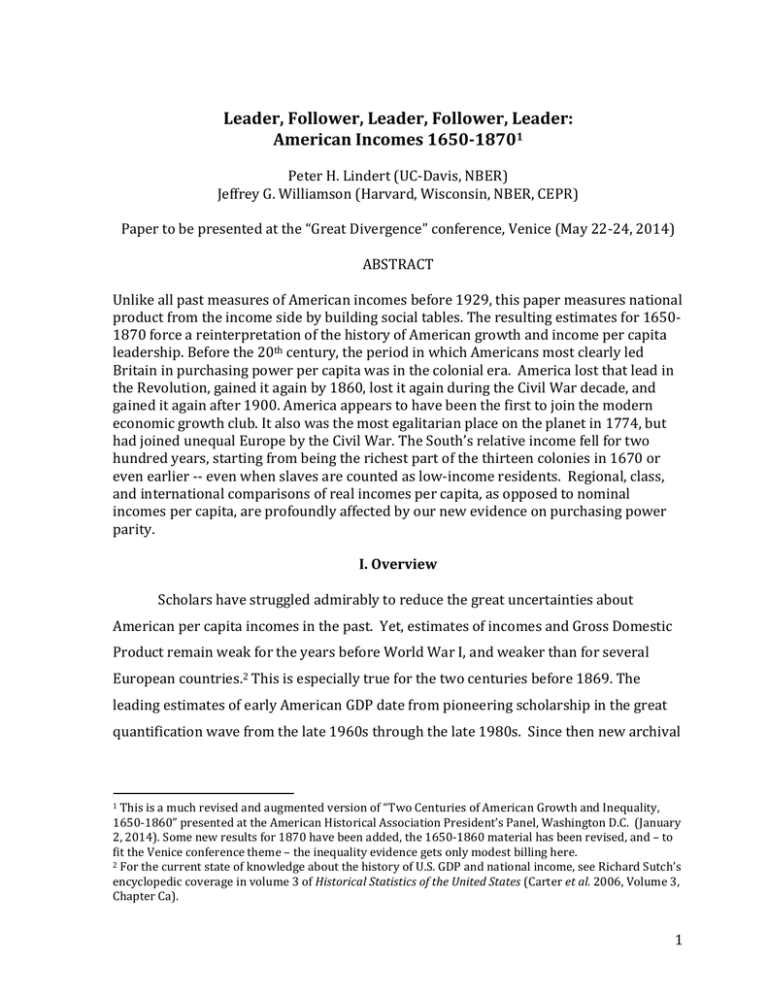

Leader, Follower, Leader, Follower, Leader: American Incomes 1650-1870

advertisement