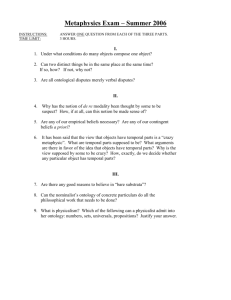

I THE MATTER OF EVENTS

advertisement