Tracking student mothers’ higher education participation and early career outcomes over

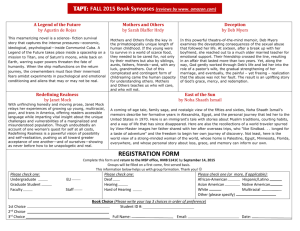

advertisement