Taking the High Road - Work, Wages and Wellbeing in the

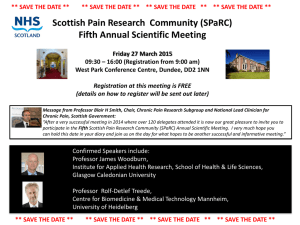

advertisement