Document 12304944

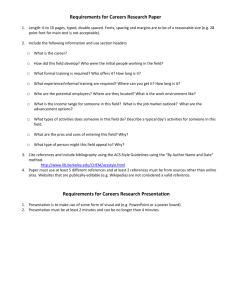

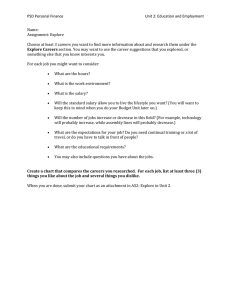

advertisement