Sabka Saath, Sabka Vikas: India and ‘competitive federalism’?

advertisement

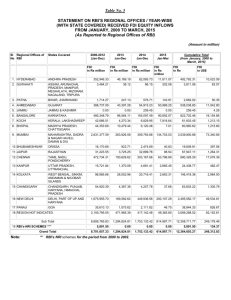

Sabka Saath, Sabka Vikas: India and ‘competitive federalism’? Meghalaya Jammu & Kashmir Mizoram Sikkim 7.23 Tripura 9.29 Andaman & Nicobar Islands 9.73 Chandigarh 10.04 Uttarakhand Assam Bihar Pudacherry Goa 13.36 14.84 16.41 17.72 21.74 Karela 22.87 Himachal Pradesh 23.95 Punjab Delhi** Haryana Telangag Tamil Nadu** West Bengal Uttar Pradesh Karnataka** Maharashtra** Odisha Pajasthan Madhya Pradesh Chhattisgarh Jharkhand Andhra Pradesh** Gujarat** 36.73 37.35 40.66 42.45 44.58 46.90 47.37 48.50 49.43 52.12 Principal-agent problem With increased state competition and decentralisation beginning in 1991, the accountability mechanisms that ensure that the Indian regional states are responsive to the nation’s wishes are now fewer and less powerful. Prime Minister Modi’s “Together with all, Development for all” is increasingly challenged by the clash of interest between the federal government and the individual states. One example is the World Bank Group’s Doing Business ‘Ease of Doing Business’ ranking of Indian states. This score benchmarks economies with respect to regulatory best practice, showing the absolute distance to the ‘frontier’ of best performance. A closer look at what ‘regulatory best practice’ entails reveals that the methodology falls straight into the competition 61.04 agenda by assuming that 62.00 minimal regulation and 62.45 taxes for business 63.09 are always best. 70.12 71.14 * Source: Asessment of State Implementation of Business Reforms, September 2015, India Department of Industrial Policy and Promotion ** These states accounted for more than 70% of FDI equity flows to India in the period Apr. 2000 to June 2012. Source: Reserve Bank of India. “Regional Inequality in Foreign Direct Investment Flows to India: The Problem and the Prospects” Bibliography/References: Anguelov, Nikolay. Dec 2015. Lowering The Marginal Corporate Tax Rate: Why The Debate? http://publicpolicycenter.org/portfolio-item/lowering-the-marginal-corporate-tax-rate-why-the-debate/ Watson, Matthew. Feb 2016. Thorstein Veblen: The Thinker Who Saw Through the Competitiveness Agenda. http://foolsgold.international/thorstein-veblen-the-thinker-who-saw-through-the-competitiveness-agenda/ 1 Gujarat government website:http://www.gujaratindia.com/business/special-economic-zones.htm ² Reserve Bank of India. “Regional Inequality in Foreign Direct Investment Flows to India: The Problem and the Prospects” 3 Another example was recently found by the European Competition Commissioner in relation to leaked information concerning special deals between Luxembourg and Starbucks and Fiat. 4 The methodology cites among others: Djankov et al. The Effect of Corporate Taxes on Investment and Entrepreneurship, American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, July 2010. In the abstract: “[greater] effective corporate tax rate have a large adverse impact on aggregate investment, FDI, and entrepreneurial activity” which this author disputes. And Botero and others, The Regulation of Labor, Quarterly Journal of Economics, June 2004 which finds “The strength of the results varies across specifications, but in general they show no benefits, and some costs, of labor regulation.” p.24 Such is the disparity of investment flows that the blue bubbles signify where investment has been magnified by a scale factor of 10. The region of Patna, home to 11% of the Indian population in Bihar and Jharkhand, received a paltry 0.061% of FDI in the period. Number of Special Ecomomic Zones (SEZs) Source: Government of India, List of Operational SEZ in India-Source-SEZ India Repeated cooperation games The tendency of state competition to race-to-the-bottom can be demonstrated through repeated games. A state government can choose to cooperate with other state governments by not engaging in the race or they can choose the route of competition. One state’s choice to compete triggers further deviation towards competition as the repeated games are influenced by the expected strategy of the other player, hence the strategy choice of the previous game, resulting in a deterministic strategy. State competition makes it increasingly difficult for them to cooperate again within the model creating a situation of Pareto-inefficient Nash equilibrium - an assumption justified by their perceived loss if one cooperates “alone”. From the games we can see the Principal-Agent problem: the sum of the payoffs, understood as the nation’s overall gains (tax revenues, economic growth, increased living standards), is not necessarily the prefered strategy for the individual players. Our game attempts to illustrate India’s development since liberalisation began in 1991: Indian legislation and policies increasingly favoured marketorientated approaches and expanded the role of private and foreign investment. States responded differently to liberalisation; some reducing labour legislation, cutting corporate tax and others continuing the pre-liberalisation strategy of national ‘cooperation’. Liberalisation was an exogenous factor in the first game, affecting the “autonomy” factor*. This was a necessary condition for the competition game to take place. What settled things depended upon the political climate*: different political majorities within the individual states are related to different state performances during the period, especially Modi’s BJP party; historical differences between regions influencing the prefered strategy of each state; the extent of lobbying by unions or companies; and other states decisions. 1. • Autonomy (balance of competence) Cooperate • Political party majorities • Lobbying (corporate and noncorporate) • Geohistorical context • Other states’ decisions 2. State A 50 50 Compete 20 20 55 k. State A Cooperate 55 10 10 50 50 Compete 15 15 45 State A 45 0 0 Cooperate Cooperate *Exogenous factors influencing state’s decisions: Compete Nagaland Putna State B Arunchal Pradesh The bubbles’ diameters are proportional to the percentage of FDI inflows to India that the regional offices received. The biggest bubble, representing the state of Maharashtra, is a depiction of the 35% of India’s total FDI there alone. Cooperate State During his tenure as Chief Minister of Gujarat, Modi convinced the head of Tata Motors to relocate operations in West Bengal, in the east of India, to Gujarat, in the west, through a personal message and an ready-to-go factory. This example reveals the rationale behind the competitiveness agenda which, unless checked, leads to government subsidy of investment. Tata Motors certainly won out of Modi’s deal, but West Bengalis lost jobs and Gujaratis bore the cost of the ready-to-go factory. Gujarat was also the first state to pass 1 the Special Economic Zone (SEZ) Act 2004. Direct tax benefits of the zones include: Business Reform Scores* exemption from commercial tax, sales tax, value added tax (VAT), entry tax, special 1.23 entry tax, luxury tax, entertainment tax, property tax, purchase tax (industry 3.41 2 dependent). At the heart of the ‘competitiveness’ agenda is the expectation 4.38 that governments unfairly distort markets in favour of corporate - but not 5.93 necessarily national - interests.³ 6.37 Special economic zones (SEZs) are treated as foreign soil by Indian authorities insofar as they are exempt from state and federal taxes. SEZs benefit from more flexible labour laws; especially industrial relations. Compete Why state competition and ‘competitive federalism’ are myths Governments that engage in ‘competition’ against each other to attract investment are playing with fire. To the extent that they cut taxes or otherwise incentivise companies they engage in a race-to-the-bottom with no foreseeable lower bound. Yet this is not in any sense promoting economic competition. Far from competing for market share through price or quality of goods and service, companies instead engage in using their political heft to extract rents from taxpayers who bear the costs of ‘profit maximisation’. As Professor Nikolay Anguelov finds, “tax competition may attract investment, but may not promote overall economic growth, offering support for value-extraction theories”. This shows a strong correlation between the number of SEZs and proportion of FDI. State B India arguably seeks to marketise the `business of government`. A feature of the change into a market based competitive federal system is the government’s revision of the Gadgil formula from 2000, which takes states` previous usage of allocated funds into consideration when devolving economic support from federal to state government. Advocates believe this would increase the efficiency of state governments’ use of resources, while the risk of losing future funding serves as an incentive for states to implement the necessary reforms in order to maximise funds. Left: the regional distribution of FDI against the number of SEZs over the 5 year period 2008-2013 Maharashtra Cooperate Modi`s promise: competitive federalism Conventional wisdom argues that a necessary condition for economic growth is encouraging investment. Theory suggests lowering corporate tax rates or other costs increases Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) and capital formation which then generates economic growth. By getting states to ‘compete’ against each other, Modi’s competitive federalist theory suggests that the states will draw investment and lead to raised living standards. FDI as a percentage of total FDI 2008-2013 Compete This poster has its origins in research undertaken by the authors for The Economics Debate 2016 between UCL, LSE and the University of Oxford. It was in preparation for the question “Will India be the next economic powerhouse” that much of the outline took shape. During the debate against Oxford there was much to and fro over the concept of ‘competitive federalism’ which seemed a particularly important theory with relevance to Indian and global economic policy making. State B “Sabka saath, sabka vikas” or “together with all, development for all” was Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s election promise to the people of India in 2014. No easy challenge: India will overtake China as the world’s most populous economy in the next 10 years yet remains comparatively poorer and underdeveloped. Modi’s development strategy must improve the living standards of over a billion people and deliver sustained economic growth. 50 50 Compete 5 5 30 30 -15 -15 kth game of n. In the first game, based on possibilities post-1991’s liberalisation, the game outcome was the compete-cooperate combination. The second game sees player A continuing with the compete strategy while player B changes strategy from cooperate to compete, because this is now the best response to the A’s chosen strategy. From then on, with each reiteration compete-compete becomes the result. Modi’s competitive agenda believes state competition will boost investment, economic growth and revenues all at once. Our game suggests this may be true in the short run. Yet over many repetitions, continued competition has one outcome: diminished returns to states, less ability to provide public goods and services to the Indian people and increasing social cost. Conclusion ‘Competitive federalism’ is not doing well by India. We do not suggest India is without need of reform, simply that alternative development strategies to Modi’s competitive federalism are available; ones which can encourage investment alongside an agenda of even distribution and growth that benefit the Indian people. India is not confronting this challenge alone. Freer movement of capital globally has meant that countries have found themselves engaging in competition races. Policymakers have already begun the path of cooperation in the EU through the planned Common Consolidated Corporate Tax Base, an example that India could follow. This framework is designed to work for both governments and investors. While investors have only a single set of rules to work with and also reap the rewards of better functioning societies, governments would no longer face aggressive tax planning by companies and also see taxable investment allocated to productive uses. About the authors: Amin Oueslati, Leise Sandeman and Elliott Christensen are first year Philosophy, Politics and Economics BSc students from Salzburg, Austria; Copenhagen, Denmark; and London, UK respectively. Each would like to thank Parama Chaudhury for her support throughout.