***WORKING PAPER*** DO NOT REFERENCE OR CIRCULATE WITHOUT PERMISSION

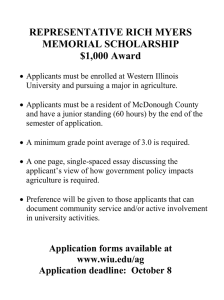

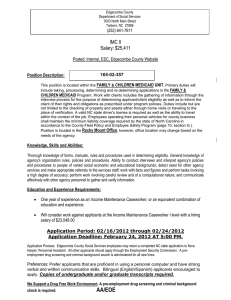

advertisement