The Development of a Teacher Salary Parcel Tax: in San Francisco

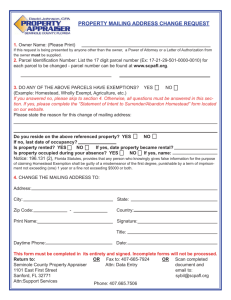

advertisement