Diversity and Economic Development: Geography Matters Nicholas Crafts

advertisement

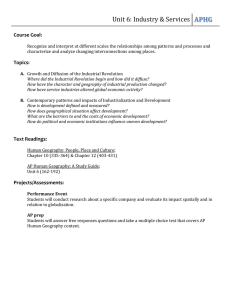

Diversity and Economic Development: Geography Matters Nicholas Crafts WEHC, Kyoto, August 7, 2015 Diversity • It’s not a neoclassical world of β and σ convergence • TFP gaps are big and technology is not universal • Different locations • Different trade specializations • Different technologies Key Questions • Who wants to produce what, where and why? • What technology is invented and used by whom? • Why might globalization promote divergence? Research Avenues • 2 promising recent developments: New Economic Geography Directed Technical Change • Ideas have run ahead of empirics; we need to put flesh on the bones • A future challenge will be to connect the two Changes in 19th-Century Economic Geography • Industrialization and de-industrialization in globalizing world • Concentration of world manufacturing production and, even more so, exports • Changes in location influenced by transport costs in the First Unbundling (Baldwin, 2012) Shares of World Industrial Production (%) 1750 1830 1880 1913 1953 2010 China India 33 30 12 4 2 15 24 18 3 1 2 2 Western USA Europe 23 0.1 34 2 61 15 57 32 26 45 24 25 Sources: Bairoch (1982) and UNIDO (2012) Shares of World GDP (%) China 1820 1870 1913 1950 1973 2010 2030 2050 33 17 9 5 5 16 28 29 India 16 12 8 4 3 6 11 16 Western Europe 23 33 33 26 26 19 13 10 Sources: Maddison (2010) and OECD (2012) USA 2 9 19 27 22 23 18 17 Historiography • Lots of explanations for 19th century continental divergence including: Imperialist exploitation (Mandel, 1975) Institutions (Acemoglu et al., 2002) Dutch Disease (Williamson, 2011) • Do NEG and DTC add anything? New Economic Geography: Key Ideas • 2nd Nature Geography matters • Agglomeration Benefits • Market Potential • Trade Costs • Globalization may imply divergence Globalization and the Inequality of Nations (Krugman & Venables, 1995) • Manufacturing goods are subject to increasing returns and are used both as final and as intermediate goods • As trade costs fall, self-reinforcing advantage of larger market leads to country-specific external economies of scale and lower costs for manufacturing in core relative to periphery • Eventually, if trade costs fall enough and/or wages in the core rise enough, manufacturing returns to (parts of) the periphery Location of Manufacturing • The ‘manufacturing belt’ in the United States is locked into place by market potential which interacts with scale and linkage effects (Klein & Crafts, 2012) • Catalonia industrializes to a much greater extent than the rest of Spain as a result of favourable market size (Roses, 2003) • Lancashire dominated the world cotton textile industry based on second nature geography (Crafts and Wolf, 2014) Market Potential and GDP 100 Years Ago • Similar impact on real GDP/person to late 20th century with elasticity of about 0.3 (Liu & Meissner, 2015) • Core Europe has much greater market potential than peripheral Asia (and Southern Europe) by the late 19th century • Changes in transport networks and shifting spatial distribution of GDP since 1820 ‘lock in’ Europe’s industrial-location advantage Market Potential (London, 1800 = 100) 1800 1870 1910 SE England 77 757 3411 NW England 61 499 1862 Kwantung 126 319 1075 Madras 80 256 1296 Source: Caruana-Galizia et al. (2015) Directed Technical Change Acemoglu (1998) (2002) • Endogenous-innovation model with bias in technical change reflecting factor endowments • Market-size and relative price effects: former dominates in 20th century but latter in 19th century? • Innovative effort based on expected profitability; innovations in ‘core’ inappropriate for ‘periphery’ and increase income gaps (Allen, 2012) The British Industrial Revolution (Allen, 2009) • “The Industrial Revolution was invented in Britain in the 18th century because it paid to invent it there” • The key is the number of potential adopters to justify fixed costs of R & D • Britain was uniquely well placed in terms of relative factor prices (wage/energy price) • Cotton textiles became a British exportable (Broadberry & Gupta, 2009) and Lancashire dominated world trade for 100 years Silver Wages, 1650-1849 (grams/day) Southern England Antwerp Strasbourg China Yanszi India 1650-99 5.6 7.1 3.1 1.4 1700-49 7.0 6.9 2.9 1.5 1750-99 8.3 6.9 3.3 1.7 1.2 1800-49 14.6 7.7 8.1 1.7 1.8 Sources: Allen (2001); Broadberry and Gupta (2006). Real Price of Energy (grams of silver/mn. BTU) 1650-99 1700-49 1750-99 1800-49 Western UK Coal 0.58 0.63 0.65 0.50 Western UK Charcoal 1.80 2.49 2.97 2.67 Antwerp Coal 6.41 7.61 6.60 5.51 5.14 7.66 12.31 13.12 10.78 Canton Puna Source: Allen (2009) Connecting NEG and DTC • This is a future challenge – no book of blueprints • Clearly there are connections: geography potentially affects market size and relative factor prices and thus the direction of technical change (cf. the Habakkuk controversy) • Successful agglomerations (cf. Lancashire) and better market access (Head & Mayer, 2006) raise wages