Coleman Campbell 1 Micah Coleman Campbell Prof. Doug Sackman – Hist 400B

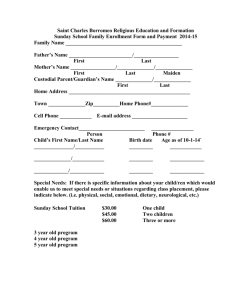

advertisement

Coleman Campbell 1 Micah Coleman Campbell Prof. Doug Sackman – Hist 400B May 13, 2011 Morality, Piety, and Muscular Christianity: Lessons in Manliness from Mid-Nineteenth Century American Sunday School Books “To be men, honest and faithful men, true to your Maker, to your own destiny, and to the land in which your lot is cast, is the noblest purpose you can form – the highest achievement you can make. This is important for you to realize at the outset. Life is in all cases and of necessity burdened with weighty responsibilities; and, happy is the youth who braces himself to meet and bear them manfully.” -David Magie, The Spring-Time of Life, 18551 David Magie is not well remembered today – nor should he be. There is little known of the Presbyterian preacher and author. Whatever his accomplishments might have been, few have been deemed worthy to be recorded in the annals of history. A couple of his books survive today, but neither contain revolutionary ideas nor masterful prose. Yet Magie's life was not without consequence; He was a part of something greater. He was one of many American Sunday School book authors of the mid-nineteenth century and these authors held incredible sway. Their books are as forgotten as their names, but in their day Sunday school books were widely read. A generation of young men grew up reading the books of Magie and his contemporaries. From these books boys learned what it meant to be a man, but more than that, they learned that becoming a man was a sacred duty – a duty their friends and family were depending on them to fulfill. Sunday school books thus placed incredible weight upon the shoulders of boys transitioning into manhood. However amidst these great expectations Sunday school books offered conflicting messages and unclear instructions on how men might meet those great expectations, undoubtedly causing more angst than relief for many men of the 1840's and 1850's. While men may have handled the tensions between the expectations put upon them and the 1 David Magie, The Spring-Time of Life, or, Advice to Youth, (New York: American Tract Society, 1855), 267, in Shaping the Values of Youth: Sunday School Books in 19th Century America, http://digital.lib.msu.edu/projects/ssb/display.cfm?TitleID=498&Format=jpg (accessed April 12, 2011) Coleman Campbell 2 conflicting methods given to them in any number of ways, a new strain within Christianity was on the horizon which would ease their concerns. Two years after Magie published The SpringTime of Life, the “Muscular Christianity” movement would begin, promising to ease the immense burden that Sunday school books had helped to put upon American men. This paper is about Muscular Christianity, but at the same time it examines evidence – Sunday school books of the 1840's and 50's – in which the term “Muscular Christianity” is completely absent. The purpose of this paper is to explore the variables that allowed and encouraged the movement's growth in America – to add another facet to its historiography. It seeks to uncover the movement's invisible roots and to re-imagine the circumstances of its inception. Historians have already explained the importance of feminization, immigration, empire, and industrialization in Muscular Christianity's growth, but even with all these variables considered, the movement's creation has not been adequately explained. American Sunday school books published just prior to the movement help complete the picture. A close examination of them and their evolution shows that Muscular Christianity's growth in America was facilitated by the tension created between the principles of divine providence and midnineteenth century expectations for men. Men were expected to provide for their family and positively contribute to society, and to do so through moral behavior which would allow men to dictate their fate. At the same time, men were instructed to have faith in God and to be subservient to his will. When God's will contradicted the upward mobility expected of men it created a conundrum for young men which was not satisfactorily resolved in Sunday school books. The Muscular Christianity movement offered a new perspective which put those concerns at ease. Muscular Christianity reoriented men's relation to God's will; The movement positioned men as agents rather than recipients of God's will. With this reassuring and empowering Coleman Campbell 3 perspective Muscular Christianity was able to spread and thrive in America. And spread and thrive it did, though not in one consistent form; Muscular Christianity was an incredibly diverse movement. That diversity and the movement's established historiography will first be addressed. The historiography, while helpful, has largely ignored Muscular Christianity's intellectual antecedents thus making research of popular literature in the decades prior to the movement all the more valuable. Researching Sunday school books of the 1840's and 50's reveals three main points about Christian masculinity of the period: First, growth into manhood was a very important matter; Second, males were taught that to be a man meant to act morally; Third, males were also taught to be pious – faithful to God and subservient to his will. The demands for both morality and piety sometimes created disconcerting contradictions Sunday school book conduct literature never fully resolved, but fiction moral tales brought into sharp relief. This contradiction and the resulting tension primed American men to embrace Muscular Christianity. Defining Muscular Christianity The Muscular Christianity movement is little known and even less understood in America today. Yet its presence was strong in its heyday, the 1880's – 1920's, and its ripples are still felt today. The movement gave birth to well known organizations such as the YMCA, Boy Scouts, and the Salvation Army which have been greatly influential in their own right, but the movement is also largely responsible for the popularization of body building and organized sport in America. It can be hard to believe now, but prior to the mid to late 19th century, sport (along with dance and theater) was looked down upon as a sinful waste of time and resources. The proponents of Muscular Christianity reshaped popular opinion to view team sports as molders of Coleman Campbell 4 upstanding moral men. Under their influence sport turned from scorned to praised and the landscape of American popular culture was dramatically changed. Even though the movement is largely forgotten, today the consequences of Muscular Christianity persist. “Muscular Christianity” is and always has been a nebulous term. For some adherents, Muscular Christianity was far more complex than “muscles + Christianity.” For others it meant precisely that. Dwight Moody, famous Chicago evangelist and YMCA missionary, was one of the first and most prominent American ministers to champion the compatibility of Christianity and sport.2 On the other hand, famous evangelist Billy Sunday, who was a successful baseball player as a young man, ironically did not give sport the same importance Moody did. But Sunday did wish to “strike the death blow at the idea that being a Christian takes a man out of the busy whirl of the world's life and activity and makes him a spineless effeminate proposition.”3 Social Gospelers, such as the Salvation Army, who sought to feed the hungry and clothe the poor, are often included within the movement;4 the Ku Klux Klan, which preached about a manly Jesus who was “robust” and “toil-marked,” may also be considered a part of the same general movement.5 Faced with this diversity, Clifford Putney, one of the few historians to write an entire book on the movement, reduces his description of the movement to “a Christian commitment to health and manliness.”6 Even at the movement's very beginning, its philosophy was ambiguous. The term wasn't even coined by one of its proponents. The first known appearance of the term was in an 1857 2 Clifford Putney, Muscular Christianity: Manhood and Sports in Protestant America, 1880-1920 (Cambridge & London: Harvard University Press, 2001), 2. 3 William McLaughlin, Billy Sunday Was His Real Name (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1955), in Michael Kimmel, Manhood in America: A Cultural History, (New York: The Free Press, 1996), 179. 4 Putney, 91. 5 Kimmel, 179. 6 Putney, 11. Coleman Campbell 5 Saturday Review review of Two Years Ago, a novel by Charles Kingsley.7 What's more, Kingsley didn't like the term, for he thought it was derogatory. However, the term was soon after applied to another book, Tom Brown's Schooldays, written by Thomas Hughes in the same year. While Hughes also did not use the term in his book, he fully embraced it, employing it explicitly in later books.8 Hughes described Muscular Christianity as “The practice and opinion of those Christians who believe that it is a part of religious duty to maintain a vigorous condition of the body, and who therefore approve of athletic sports and exercises as conductive to good health, good morals, and right feelings in religious matters.”9 This description should be noted, not only because it is one of the most clear ones, but because Hughes was not only one of the first muscular Christians, he was also one of the most influential. Tom Brown's Schooldays was an immensely popular book in England. Historian William Winn goes as far to say that the book was “probably the most important book ever to be written about Public Schools.”10 Common Explanations for the Movement's Growth Understanding that Muscular Christianity was influential is simple enough, but understanding why is more difficult. While Muscular Christianity blossomed in England soon after 1857, it took a couple of decades for it to truly catch on in America. Clifford Putney attributes this delay primarily to two differences between the countries.11 First industrialization wasn't nearly as developed in America as it was in England. Most American men were employed 7 Tony Ladd and James A. Mathisen, Muscular Christianity: Evangelical Protestants and the Development of American Sport (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books, 1999), 13-14. 8 William E. Winn, Tom Brown's Schooldays and the Development of “Muscular Christianity,” ATLA Religion Database, http://web.ebscohost.com/ehost/detail?sid=1a4bf82d-e360-4b7e-ae9a88e217cfbb81%40sessionmgr112&vid=1&hid=105&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZSZzY29wZT1zaXRl#d b=rfh&AN=ATLA0000668609 (accessed March 25, 2011), 67. 9 Merriam-Webster Dictionary, “Muscular Christianity,” http://www.websterdictionary.net/definition/Muscular%20Christianity (accessed March 25, 2011). 10 Winn, 66. 11 Putney, 23. Coleman Campbell 6 in hard agrarian labor which naturally created a more physically fit population, so there would have been less concern about an effeminate and weak manliness. Secondly, the American Civil War, which enlisted three million men and killed 620,000, temporarily silenced any questions of the manliness of American men.12 However, by the 1880's the Civil War was a fading memory and American industrialism was in full swing. “A professional or businessman, what muscles has he at all?” asked Thomas Higginson, a writer for the Atlantic Monthly, expressing the concern of many of his contemporaries that the new labor market was producing a generation of effeminate men.13 At the same time, emigration to the United States was on the rise; most scholars believe this propelled Muscular Christianity's growth, but they don't all agree how. Putney and Michael Kimmel emphasize Anglo-Saxon men's fear of immigrants and consequent desire to be the stronger, manlier race.14 Tony Ladd and James Mathisen, however, note that some social Gospelers assumed immigrants were less physically fit and so created fitness programs meant to serve this apparent need in the immigrant community.15 Finally, women's growing voice in the church and in America at large, is commonly designated as another and perhaps the most influential cause of Muscular Christianity's popularity. Ann Douglas, in her book The Feminization of American Culture, argues that in the 19th century, particularly by the end of it, American Christianity had become effeminate, upholding traditionally feminine traits such as emotion, empathy, and passivity.16 Putney imagines Muscular Christianity as an insecure reaction to this “feminization.” Men afraid of appearing effeminate, he argues, emphasized all of its opposites: action, strength, and insensitivity.17 12 PBS, “The Civil War: A Film by Ken Burns, Fact Page,” http://www.pbs.org/civilwar/war/facts.html (accessed March 25, 2011). 13 Thomas Wentworth Higginson, “Saints and Their Bodies,” Atlantic Monthly 1, 1858, in Kimmel, 177. 14 Putney, 8. Kimmel, 194. 15 Ladd and Mathisen, 43. 16 Ann Douglas, The Feminization of American Culture (New York: Avon Books, 1978). 17 Putney, 75. Coleman Campbell 7 The belief that Muscular Christianity was a movement motivated almost entirely out of insecure reactions to simultaneous trends is the established historical explanation. One gets the sense that had there been no industrial revolution, dramatic increase in immigration, and feminization of the church, Muscular Christianity would not have come about. This would be akin to saying the American Revolution happened because George III taxed without representation and passed the Quartering Act. These were certainly a part of it, but to explain the revolution's cause this way neglects the colonies' individuality and agency. It does not mention that as near autonomous entities, the colonies had created, practiced, and by 1776 expected some form of representative government. In the same way, if we focus on how other movements acted upon Christian males at the expense of how Christian masculinity was perceived and taught prior to the movement, we do not see the whole picture. In short, a change of perspective is needed, not to revoke, but to supplement existing theories on Muscular Christianity's genesis. Sunday School Books as Sources To examine the roots of Muscular Christianity, this paper turns to Sunday school books of the 1840's and 50's. Children's books can bring into focus the values of two generations simultaneously. By reading Sunday school books of the 1840's and 50's, by looking at what values those books sought to teach children, historians can surmise what values Christian adults held in the 1840's and 50's. By the same token, examining those books, what they taught, and how they taught it, may allow historians to gain some insight into what the children believed and/or why they believed what they did. And since many of these children would grow up to be some of the first muscular Christians, this is an especially useful facet. That said, Sunday school literature has its limitations. It cannot be assumed with absolute certainty that what was taught to Coleman Campbell 8 children is what they learned. Furthermore, we should not completely accept that what book authors taught is what they believed. Ann Scott MacLeod, author of A Moral Tale: Children's Fiction and American Culture, 1820 – 1860, reminds her readers that “[F]ew adults... are entirely frank or wholly realistic in what they tell children about the world.”18 Sunday school books should not be discounted as sources of evidence, but they should be read with their limits in mind. Additionally Sunday school books are a prime source because they were widely circulated and read. In 1832 there were 8,268 Sunday schools affiliated with the American Sunday School Union nationwide.19 79% of those schools reported having a library; the average library possessed 91 books.20 Few of these books have passed the test of time. Most were simple in scope and language since their stated objective was to teach more than to entertain. Nevertheless, the books were well read in their day. Professor Stephen Rachman of Michigan State University remarks that this “mass of juvenile literature is as forgotten as it was once pervasive.”21 Sunday school books, like the Muscular Christianity movement, have been mostly forgotten today, but like Muscular Christianity, Sunday school books were highly relevant in their time. ~~~ The Importance of Manhood “A youth leaving home! There is something not a little melancholy in the idea,” opens 18 Anne Scott Macleod, A Moral Tale: Children's Fiction and American Culture, 1820-1860 (Hamden, CT: Archon Books, 1975), 10. 19 Anne M. Boylan, Sunday School: The Formation of an American Institution, 1790-1880 (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1988), 31. 20 Ibid, 50. 21 Stephen Rachman, “Introduction,” Shaping the Values of Youth: Sunday School Books in 19th Century America, http://digital.lib.msu.edu/projects/ssb/?action=introessay (accessed March 25, 2011). Coleman Campbell 9 The Young Man From Home, an 1840's22 advice book by John Angell James to young Christian men.23 James notes that, “It is at home that parents and children, brothers and sisters, as long as Providence permits them to dwell together, mingle in the sweet fellowship of domestic bliss.” James, like many of his contemporaries, was immensely concerned with young boys' transition into adulthood; even as there was “something not a little melancholy” in a youth leaving home, there was something not a little momentous as well. Though as James empathized with the pain of a youth leaving home, he insisted, “[i]t is the appointment of God that man should not live in idleness, but gain his bread by the sweat of his brow; and you must be placed out in the world to get yours by honest industry.”24 The transition from boyhood to manhood was nothing less than an event of divine importance. This view was also held by Christian adults and authors the country over. “[W]riters of juvenile fiction were caught up in a preoccupation with the future,” Anne Scott MacLeod noted. “[T]hese writers believed... [d]emocracy would stand or fall by the moral qualities of its citizens, and these in turn were dependent upon the early training of the young.”25 As such, the transition into manhood was treated with the utmost seriousness by parents, preachers, and neighbors alike. The pitfalls along the road to manhood were many and if a boy were to fall in, not only they, but their family and community, would suffer. Fortunately, boys did not have to travel the road to manhood alone. Because Americans believed the Republic's future depended on properly raising the next generation of men, a large portion of Sunday school books published in this time period (1840's and 50's) were devoted to teaching Christian boys and young men how to behave. This genre may be called “conduct 22 The precise date of the book is not determined. Only that it was almost definitely published in the 1840's. 23 John Angell James, The Young Man From Home, (London: Religious Tract Society, 184-?), 5, in Shaping the Values of Youth: Sunday School Books in 19th Century America, http://digital.lib.msu.edu/projects/ssb/display.cfm?TitleID=578&Format=jpg (accessed April 12, 2011). 24 James, 6. 25 Scott MacLeod, 39,40. Coleman Campbell 10 literature.” Written as if spoken directly to the reader, conduct literature served as a sort of manual on life, instructing readers how to overcome temptations, interact with others, and carry out their everyday lives. These books, often stripped of any sort of narrative, were not entertaining, but they weren't intended to be. Manhood was a serious issue and Sunday school book authors wanted to make sure that they clearly demonstrated to boys how to properly mature. The irony and tragedy is that in some key issues Sunday school books were not clear. The books were able convey the gravity of the situation – how important boys' conduct was – but they did not make clear exactly what conduct should be followed. They simultaneously told young men to take their lives into their own hands and to submit to God's will – two often opposing actions. What it Meant to Be a Man To understand how mid-nineteenth-century men were supposed to behave, it must first be understood what it meant to be a man in the mid-nineteenth century. Unlike current popular understandings of masculinity which usually place women and femininity as its opposite, Sunday school books of the 1840's and 50's more often placed manhood in opposition to boyhood. Daniel Wise, author of The Young Man's Counsellor, wrote, “As a boy, at home, you have sailed upon the calm waters of a quiet river... Now, you are sailing through the winding channels, the rocky straits, the rapid, rushing currents, at the river's mouth, into the great sea of active life.”26 Wise makes a clear distinction between the easy and simple life living as a child at home and difficult and dangerous life living alone as a young man. The departure from home meant a 26 Daniel Wise, The Young Man's Counsellor, or, Sketches and Illustrations of the Duties and Dangers of Young Men, (New York: Carlton & Phillips, 1853), 18, in Shaping the Values of Youth: Sunday School Books in 19th Century America, http://digital.lib.msu.edu/projects/ssb/display.cfm?TitleID=488&Format=jpg (accessed April 12, 2011). Coleman Campbell 11 departure from innocence. More to the point, Wise adds, “here for the first time, you are in command of your vessel.” As it is today, manhood was closely linked with power. Adult life held many temptations and dangers, but it was expected that each man steer clear of them. Whereas boys were at the mercy of their parents' direction, men were the master's of their own fate. Furthermore, the optimistic belief that men could control their destiny (should they choose to), was not limited to any one subsection of men. Men of every class and color apparently had the same opportunity.27 In fact, the relative success each man had in controlling their destiny, was itself a measure of their manliness. David Magie concluded, “Hence it comes to pass that almost all real men... are self-made men. We see this everywhere.”28 “Self-made men” were those men who worked their way up the social ladder without the aid of a large inheritance or corrupt practices. The “self-made man,” now an iconic term in American discourse, was not always so supremely upheld, but as Kimmel writes, “By the 1840's and 1850's a veritable cult of the Self-Made Man had appeared.”29 The self-made man's popularity reflects a widespread belief that men were in control of their fate – that regardless of their circumstances they could, and should, surpass them. Therefore, those who did not achieve economic success were blamed and those who did were praised. Unlike boys, who were to be subservient to their parents, men supposedly had full control of their fate and were thus expected to exercise it. Manliness was predominately perceived in opposition to boyishness, but it was thought of in opposition to femininity as well. In the short story, “Tender-Hearted, Forgiving One Another,” the bully, Jack, sneers that Willy, the protagonist, is a “girl-baby,” calling into question both Willy's physical maturation and gender.30 The line drawn between men and women had been 27 28 29 30 This is not to say that each man had equal opportunity in reality – only in common perception. Magie, 271. Kimmel, 26. Lynde Palmer, Helps Over Hard Places: Stories for Boys, (Boston: American Tract Society, 1862), 30, in Coleman Campbell 12 growing clearer since the republic's birth and by the mid-nineteenth century men and women held distinct roles in society. Popularly known as “separate spheres,” men were expected to operate in the public sphere (politics and economics) while women were expected to operate exclusively in the private sphere (the household). Thus specific duties were given gendered connotations. Child rearing, cleaning, and cooking increasingly became womens' roles while wage earning and all things politics became fundamental aspects of a man's manliness. If the dominant theme of manlhood in opposition to boyhood was increased control and the prevailing divide between men and women was the separate spheres they inhabited in society, then men by nature of this distinction carried much responsibility. Men supposedly held the power to shape their circumstances and since it was overwhelming men who were expected to bring about material advancement and participate in society at large, the fate of American families and, indeed, the country, depended on men properly exercising their powers. Author T.S. Arthur argued, “Money should be considered as a means by which man has power to act usefully in the world and he ought to endeavor to obtain it with that end in view.”31 Arthur was hardly alone. Sunday school book authors' concern that the next generation of men live up to the great responsibilities put upon them permeates their books. For example, “I simply ask, what will that youth accomplish in the after-time of his life?” Daniel Wise asked simply, but not casually. “If he have mercantile skill, will he employ it... to gratify his lust of wealth; or to elevate and bless humanity?”32 James Hamilton asked his readers, “What are you doing? What are you contributing to the world's happiness or the church's glory? What is your business?”33 Manhood Shaping the Values of Youth: Sunday School Books in 19th Century America, http://digital.lib.msu.edu/projects/ssb/display.cfm?TitleID=451&Format=jpg (accessed April 12, 2011). 31 Timothy Shay Arthur, Advice to Young Men on Their Duties and Conduct in Life, (Boston: Phillips, Sampson, 1850), 27, in Shaping the Values of Youth: Sunday School Books in 19th Century America, http://digital.lib.msu.edu/projects/ssb/display.cfm?TitleID=567&Format=jpg (accessed April 12, 2011). 32 Wise, v. 33 James Hamilton, Life in Earnest, or, Christian Activity and Ardour, (Philadelphia: American Sunday-School Coleman Campbell 13 carried with it not only many expectations of worldly action, but also great pressure to meet them. Fortunately for young men of the mid-nineteenth century, Sunday school books authors were eager to instruct young men how to meet those expectations. Despite the free-market capitalistic conditions which they lived in, authors did not encourage young men to be aggressive, individualistic, or cunning. Rather, as David Magie put it, “The land calls for modest, quiet, sober-minded youth.”34 Had authors simply wanted to produce men who would be economically successful, they might have included the previously mentioned traits. But they were hoping to train good Christian men, which not only altered their goals, but also the methods by which they sought to attain those goals. Consistently, authors argued that the single most important quality a man must posses in order to provide for his family and society was morality. Morality The first step to piety, the means by which men might control their fate, was in fact selfcontrol. Daniel Wise warned, “Indulge your appetites, gratify your passions, neglect your intellect, foster wrong principles, cherish habits of idleness, vulgarity, dissipation, and... you will reap a plentiful crop of corruption, shame, degradation, and remorse.”35 But he was not without hope, for he continued, “if you control your appetites, subdue your passions, firmly adopt and rigidly practice right principles, from habits of purity, propriety, sobriety and diligence, your harvest will be one of honor, health, [and] happiness.”36 Here and elsewhere authors insisted that young men learn to master their impulses and restrain their darker desires. Consistently men Union, 1845), 27, in Shaping the Values of Youth: Sunday School Books in 19th Century America, http://digital.lib.msu.edu/projects/ssb/display.cfm?TitleID=489&Format=jpg (accessed April 12, 2011). 34 Magie, 276. 35 Wise, 16. 36 Wise, 17. Coleman Campbell 14 who could not control their desires were put at odds with desirable men. T.S. Arthur began his book with the assumption “that there were two classes of young men – one made up of those who feel the force of good principles... and the other composed of such men as are led mainly by their impulses... [S]ociety looks to the former as her regenerators.”37 Undoubtedly such selfmastery was partially meant to prevent sin, but within Sunday school books, more emphasis was put on the great character self-control builds. “I wish you to direct your most serious attention to the importance of character, moral and religious character,” John Angell James instructed his readers. “What is every thing else without character? How worthless is man without this!”38 The answer was so obvious it didn't need an answer; men without self-control or character were worth little to the community in which they lived. However, moral character meant more than the ability to control evil desires. It also required the regular application of positive traits. Sunday school books were littered with strongly recommended traits thought to bring about great character – integrity, frugality, intelligence, generosity were among the most common. But more than any other character trait, industry39 was upheld as key to a man's successful life. “[I]t is the man of persevering industry, who is happy in his own bosom, and who contributes to the happiness of others,” T.S. Arthur claimed.40 Daniel Wise recommended that “every young man should engrave on his heart – that industry is essential to the enjoyment of life.”41 James Hamilton had so much to say on the matter that his book's first chapter, titled “Chapter I: Industry,” is followed by a chapter with the near identical title, “Chapter II: Industry.”42 Indeed, it seems Sunday school book authors' energies for 37 Arthur, 3. 38 James, 7. 39 “Diligence” or “hard work” are interchangeable here and in the books with “industry.” Industry, however, was the word most often used to describe the same concept. 40 Arthur, 158. 41 Wise, 107. 42 Hamilton, 7 & 25. Coleman Campbell 15 writing about industry were near boundless. The emphasis on industry should not be surprising; it is a logical companion to the “selfmade man” ideal. The self-made man ideal assumes (with some variation) that economic advancement is a matter of choice – that if a man wishes to progress up the social ladder, and furthermore, if he is willing to work hard to do so, such an end is well within his grasp. Thus while industry may have intrinsic value as a moral good, it also had practical value for the young men aspiring to provide for their families and society. The same can be said of many of the other often recommended character traits within Sunday school books. A frugal man would steer clear of debt; an intelligent one would invest wisely; generous and honest men would be more likely to receive generosity and honesty in kind. With most of the moral behaviors conduct literature emphasized, young men could easily see the potential beneficial consequences. The significance of esteemed character qualities' practicality should not be dismissed. By putting character traits that bring about sensible consequences on a pedestal, Sunday school teachers gave men an almost tangible means to change their circumstances. If men wished to meet the expectations put upon them – that they provide for their family and contribute positively to society – they were told that they contained the means within themselves. They were told they had great power; the key to unlocking it was moral behavior, as the final paragraph in Arthur's Advice to Young Men illustrates: From this view every young man can see how great is the responsibility resting upon him as an individual. If he continues with right principles as his guide, - that is, if in every action he have regard to the good of the whole, as well as to his own good, - he will not only secure his own well-being, but aid in the general advancement towards a state of order. But if he disregard all the precepts of experience and reason, and follow only the impulses of his appetites and passions, he will retard the general return to true order, and secure for himself that unhappiness in the future which is the invariable consequence of all violations of natural or divine laws.43 43 Arthur, 178. Coleman Campbell 16 Piety The message given to young men that they could meet gendered expectations through exercising moral behavior was no doubt a compelling and comforting one, but it was not the only one. Christian men were taught to be more than moral; they were taught to be pious. The author44 of The Factory Boy explains the distinction: “There are two classes of duties which belong to us – first those we owe to God; and, secondly, those we owe to men... [M]orality consists only of this last kind of duties... but the first kind of duties are most important.”45 A moral man seeks to benefit other people, she argues, while religious or pious men do the same in addition to serving God. “A person may be a moralist, and not a Christian; but no one can be a Christian, and not a moralist.”46 For Sunday school book authors, this distinction was hardly superfluous. “[Y]ou may be already moral and upright, and thus be led to imagine that you are prepared to repel every attack,” but it would be a mistake to think so, John Angell James warned.47 “[M]orality may protect you, but piety will.” Sunday school book authors wrote extensively about the importance of moral character, but they certainly did not neglect to remind readers to be pious. Christian men were unsurprisingly expected to be pious and while that did not contradict desires to be moral (in fact it complimented them), it did complicate how Christian men were expected to fulfill their obligations to their families and society. At the heart of piety is faith – faith in God's existence, but more importantly in the context of this paper, faith in God's superiority and will. Sunday school book authors acknowledged men's great power within America, but there was never any confusion about their status in relation to God. “Adopt... that 44 Authorship is credited to “A Lady.” 45 A Lady, The Factory Boy, or, The Child of Providence, (Philadelphia: American Baptist Publication Society, 1839), 27, in Shaping the Values of Youth: Sunday School Books in 19th Century America, http://digital.lib.msu.edu/projects/ssb/display.cfm?TitleID=460&Format=jpg (accessed April 13, 2011). 46 A Lady, 28. 47 James, 88. Coleman Campbell 17 religion which exalts God on the throne of the universe, and lays man low in the dust at his footstool,” exhorted David Magie with humbling imagery.48 Men were clearly subservient to God and in their subservience there was an acknowledgment that they ought to be subject to God's will. “The believer is the happy captive of Jesus Christ; he has fastened on himself Immanuel's easy yoke,” said James Hamilton, offering a vivid metaphor of man's relationship with God.49 The God-human hierarchy was not an abstract issue of little importance to mid-nineteenth century men, because most believed in a God who was very involved in the day to day workings of the temporal world. The books speak of a God who is willing to and regularly alters humans' lives in order to shape their fate; this direct intervention was often called “Providence.” As servants to their Lord, it was expected that men not stray from God's designs, which was simple enough when God seemed to be blessing them with good fortune, but was a much more difficult and confusing task when God was less generous, as he was prone to be on occasion, even to morally upright men and women. “Sometimes the providence of God sees fit to afflict the virtuous,” the author of The Factory Boy admitted.50 Such unfortunate scenarios surely brought up a difficult question for mid-nineteenth century men: should men facing affliction continue to work hard to try to surpass their station in life or should they remain content with what may appear to be God's design, since fighting Providence would mean disobeying God? Should men always seek to progress or instead be satisfied with their lot? Unfortunately, Sunday school authors did not provide consistent or clear answers between texts or even within a single one. James Hamilton said, men “should seek, for the sake of the 48 49 50 Magie, 282. Hamilton, 45. A Lady, 15. Coleman Campbell 18 gospel to be first-rate in his own department,”51 but David Magie insisted, “[t]urn now to man as society requires him to be, and as he must be to fill his proper place.”52 William Newnham stated “it is a clear and fundamental law of Omniscience, that each one of his creatures is fitted for the position he has appointed it to fill; and we are not to contravene that law... we are called upon to accept it with gratitude.”53 Newnham clearly seems to have been against upwardly mobile men, but less than a page later he adds, “man should be progressive... [F]rom the cradle to the grave his powers should be developing.”54 Matters were further complicated when looking at the effects of moral behavior with Providence in mind. Men were taught that they could positively alter their fates through moral behavior, but if they also were told that God intervenes in this world, sometimes to the benefit of the wicked and to the detriment of the righteous, then how much did their actions truly matter? Should they simply have acted justly and hoped God rewarded them for it? These questions too were not sufficiently addressed or satisfactorily answered, which may have been especially disconcerting because Providence, morality, and piety were commonly intertwined in ways that were often ambiguous, but not often consistent. John Angell James conflated all these ideas in his recounting of the biblical story of Joseph: “But Providence, ever watchful over the reputation and interests of pious men, overruled all for good, and made the prison of this industrious Israelite the way to his elevation”.55 Sunday school book authors were very clear about what was expected of Christian men, but the authors delivered mixed, sometimes contradictory, messages about how to meet those expectations. They insisted men had extreme power to shape their lives and should constantly endeavor to use that power, 51 Hamilton, 34. 52 Magie, 272. 53 William Newnham, Man, in His Physical Intellectual, Social, and Moral Relations, (Philadelphia, VA: American Sunday-School Union, 1847) vii-viii, in Shaping the Values of Youth: Sunday School Books in 19th Century America, http://digital.lib.msu.edu/projects/ssb/display.cfm?TitleID=552&Format=jpg (accessed April 13, 2011). 54 Ibid, viii. 55 James, 87. Emphasis added. Coleman Campbell 19 but ultimate authority was given to God who intervened in the lives of men in ways that were not necessarily predictable or immediately understandable. Sunday school books of the 1840's and 50's thus reveal a tension of the time between expectations for men and how they were supposed to meet them. Moral Tales This tension, only hinted at in conduct literature of the 1840's and 50's, came into sharp relief in the fictional moral tales of the same period. Moral tales taught many of the same ideas and made many of the same normative claims as those found in conduct literature. The expectation that men provide for the family and contribute to society was so readily assumed that it hardly bore mention; whenever sudden misfortune stripped a family of its father, the family always descended into desperate times (at least temporarily) for women and children could not adequately provide for the family without the aid of others and/or God. Like the conduct literature, moral tales suggested that both morality and faith were the means for men to meet expectations and moral tales also painted an unclear picture of how all these elements worked together. In “The Doctor's Family,” the family is flung into poverty after the father's death, but they are eventually rescued by a generous donation of money from a stranger who the father had helped before he passed away – the moral of the story being moral behavior will be rewarded.56 However, in the story, “The Sailor,” a crew of sailors are saved from the frozen tundra only by the faith of one sailor who believed God would save them if they let loose the ship's sails (when 56 “Cousin Cicely,” The Cornucopia: A Collection of Pieces of Prose and Rhyme for the Silver Lake Stories, (Auburn, NY: Alden and Beardsley, 1855), 11-34, in Shaping the Values of Youth: Sunday School Books in 19th Century America, http://digital.lib.msu.edu/projects/ssb/display.cfm?TitleID=463&Format=jpg (accessed April 14, 2011). Coleman Campbell 20 others were sure the great winds would destroy the masts should the sails be let down).57 In the first story, a man is able to provide for his family (even in death!) by leading a moral life. In the second story, the characters only survive because one man was willing to give up all power to God. Once again – in moral tales like in conduct literature – it was unclear for young men how best to act. That said, it's somewhat remarkable that young men had any Christian moral tales to read at all. American Christians of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries sharply criticized fiction and strongly resisted publishing any of their own. “The concern with fiction lay in the sense that not only could it lead to fantasy or sensationalism,” Professor historian Stephen Rachman explained. They worried that it could also lead to a “kind of license with scripture itself, unorthodox or personal interpretations, and secular opinion.”58 However, regardless of what their parents thought, young Americans preferred the exciting tales of fiction books over the tedious instruction of conduct literature – so much so that Christians grudgingly began to publish their own fiction to teach the children proper morals. Sunday schools, whether they liked it or not, realized moral tales were what children wanted to read and so figured it was better to risk unorthodoxy than let children learn their morals from secular fiction. By the middle of the nineteenth century, moral tales was the fastest growing category of book published by Sunday school unions.59 Nonetheless, those Christians who worried that fictional stories would lead to unorthodoxy and personal interpretations may have been well justified, for moral tales taught 57 The Casket for Boys and Girls, (Concord, N.H.: Meriam & Merill, 1854), 3-22, in Shaping the Values of Youth: Sunday School Books in 19th Century America, http://digital.lib.msu.edu/projects/ssb/display.cfm?TitleID=551&Format=jpg (accessed April 14, 2011). 58 Stephen Rachman, “Moral Tales,” Shaping the Values of Youth: Sunday School Books in 19th Century America, http://digital.lib.msu.edu/projects/ssb/index.cfm?CollectionID=60 (accessed April 14, 2011). 59 Ibid. Coleman Campbell 21 lessons their authors may have never meant them to. One of the most common themes among moral tales of the period was about power-stripped men and boys. “The Capsized Boat” tells the story of two good boys who are persuaded by a larger more mischievous boy to take their father's boat out into the lake against his explicit instructions.60 However, once the three boys row into deeper waters, the two younger ones realize they made a mistake and beg to return. But the oldest boy refuses and since they are too small to force him otherwise, they are unable to avoid the eventual storm which nearly kills them. Two older men who spot the boat are able to rescue the two boys before they drown. In the “The Doctor's Family” story, the eldest son is unable to take his deceased father's place as the family's main provider because of a spinal condition which has rendered him “perfectly helpless.”61 In fact, the son is so helpless that his sister must pull him on a cart to get to town. This would have been a powerful image (literally drawn on page 27, Fig. 1) for readers because it calls to attention not only the son's weakness, but also that his sister must do hard labor for the family because the son is so ineffectual in living up to his obligations as a man. Why the theme of powerless males was so common in moral fiction is debatable. It seems likely that their powerlessness was a narrative practicality to show the necessity of God's grace and Providence. However, as much as these books taught boys to be moral and faithful, they also taught boys that men without a lot of individual self-reliant power would get trampled over. In these stories, God saves the protagonists eventually, but had the men/boys had more power within themselves initially, their problems could have been solved much sooner. If the boys in “The Capsized Boat” were stronger they could have steered their boat back to safety; if the son in “The Doctor's Family” had not been bed-ridden he might have supported the family without 60 61 Cousin Cicely, 119-146. Ibid, 22. Coleman Campbell 22 the need for others' generosity. Even as these stories taught the importance of faithfully believing in Providence, they suggested that should individual men possess enough power, they could avoid a lot of hardship that would have been suffered had they waited for God's intervention. Fig. 1 - “Julie and Walter” - Not the male ideal Thus in the years leading up to 1857 (the official birth of Muscular Christianity), Christian men were given clear ideas about what was expected of them, but unclear ideas about how they should go about meeting them. On the one hand, they were instructed to control their own destiny with moral behavior; on the other, they were told that it was God who shaped their destiny and that it would be unfaithful to try to oppose God's designs. Muscular Christianity represents an effort made to address those conflicts. While it is difficult to encapsulate the entire movement with one definition every strain within it held in common a desire for the ability to control one's circumstances whether they be inner demons, physical obstacles, societal barriers, Coleman Campbell 23 economic loss, etc. Donald Hall, editor of Muscular Christianity: Embodying the Victorian Age, identifies “a central, even defining, characteristic of Muscular Christianity: an association between physical strength, religious certainty, and the ability to shape and control the world around oneself.”62 The key word here is “ability.” All muscular Christians did not necessarily always want to control others or their circumstances; they did not always want to fight. But what they did want was the ability to, should the occasion ever necessitate that power. Muscular Christians wanted to be powerful, but not at God's expense. On the contrary, they wanted to be powerful in order to carry out his wishes. The shift in thinking can be seen within Sunday school books of the 1860's. One thing that had not changed from the 1850's to the 1860's was a high prevalence of bullies within moral tales. In “The Young Conqueror,” the protagonist, Hal, is made fun of for his pious behavior.63 In “Tender-Hearted, Forgiving One Another,” the protagonist, Willy, faces a bully who goes so far as to drown the Willy's beloved kitten.64 Their afflictions the protagonists face are not much different than those faced in many moral tales of the 1840's and 50's. However, how the conflicts are resolved changes significantly. Instead of waiting for Providence to save them from persecution, it is the protagonists who become the heroic rescuers. When Hal's bully cramps while swimming and nearly drowns, it is Hal who “almost by super human efforts”65 saves him. Shortly after Will's bully kills his kitten, Willy rushes into a burning farm in order to save his bully's dog. It is tempting to read stories such as Hal's and Willy's as attempts to wrest away some of God's authority and power, but to do so would be a mistake. In bully stories, the protagonists at 62 Donald Hall, ed., Muscular Christianity: Embodying the Victorian Age (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 7. 63 Palmer, 9-27. 64 Ibid, 28-37. 65 Ibid, 23. Coleman Campbell 24 the outset generally have very little interest in the well-being of their bully. However, there is always a moment when the protagonist is reminded, whether by a parent, friend, or scripture, that as Christians they are to act morally – more specifically to be industrious in the face of hard times and to be merciful to their enemies. It is only after this critical point of amending ways that tragedy strikes for the bully and the protagonist is called upon to save him. This pattern of persecution, forgiveness of persecutor, and then saving of persecutor establishes two key points for the narrative. The first is that even though the protagonist acts with considerable agency he does not relinquish his morals. The second and more important point is that the protagonist saves the bully because as a Christian he is compelled to; The protagonist has little to gain from saving the bully, but he does so because he believes God wants him to. The stories make clear that Hal and Willy's actions were not only God sanctioned, but as God intended. Hal, Willy, and similar protagonists were not fighting Providence; they were acting as agents of Providence – a remarkable change from the stories of just a decade prior and indicative of the way perceptions of how men might fulfill their familial and societal responsibilities was evolving. Fig. 2 - “Finding Captain Carle” - Male protagonists of the 1860's did not only save bullies. In the 1863 book, Kenny Carle's Uniform, the young man, George, finds and saves the injured Captain Kenny Carle.66 66 Kenny Carle's Uniform, (Boston: American Tract Society, 1863), 104-105, in Shaping the Values of Youth: Sunday School Books in 19th Century America, http://digital.lib.msu.edu/projects/ssb/display.cfm?TitleID=524&Format=jpg (accessed May 12, 2011). Coleman Campbell 25 Conclusion Muscular Christianity did not start from nothing. It was certainly fueled in varying degrees by contemporary events – most notably, the Women's Rights Movement, the Industrial Revolution, and the huge immigration increases over the last quarter of the century. But they are not the roots of Muscular Christianity. The term was coined in England and the movement's pioneers, Kingsley and Hughes, were both English, but the movement expanded to America because it was a logical extension of already held notions about what it meant to be a man, what the expectations for men were, and how men were supposed to meet those expectations. Studying Sunday school books of the 1840's and 50's reveals a consistency in expected ends for men and inconsistencies in expected means to achieve those ends. For men who found these contradictions problematic, Muscular Christianity provided a welcome solution. Muscular Christianity upheld moral behavior and it did not disparage Providence. American men did not have to give up fundamental parts of their faith; they just had to look at their faith differently. Under Muscular Christianity, men were not dis-empowered by Providence; they played an active part in fulfilling it. Muscular Christianity in part survived and eventually thrived in America because it helped to resolve gendered and theological tension that had been brewing for decades prior to 1857. Coleman Campbell 26 References: Primary Sources: Shaping the Values of Youth: Sunday School Books in 19th Century America. http://digital.lib.msu.edu/projects/ssb/index.cfm “A Lady.” The Factory Boy, or, The Child of Providence. Philadelphia: American Baptist Publication Society, 1839. in Shaping the Values of Youth: Sunday School Books in 19th Century America. http://digital.lib.msu.edu/projects/ssb/display.cfm?TitleID=460&Format=jpg (accessed April 13, 2011). Arthur, Timothy Shay. Advice to Young Men on Their Duties and Conduct in Life. Boston: Phillips, Sampson, 1850. in Shaping the Values of Youth: Sunday School Books in 19th Century America. http://digital.lib.msu.edu/projects/ssb/display.cfm?TitleID=567&Format=jpg (accessed April 12, 2011). Casket for Boys and Girls, The. Concord, N.H.: Meriam & Merill, 1854. in Shaping the Values of Youth: Sunday School Books in 19th Century America. http://digital.lib.msu.edu/projects/ssb/display.cfm?TitleID=551&Format=jpg (accessed April 14, 2011). “Cousin Cicely.” The Cornucopia: A Collection of Pieces of Prose and Rhyme for the Silver Lake Stories. Auburn, NY: Alden and Beardsley, 1855. in Shaping the Values of Youth: Sunday School Books in 19th Century America. http://digital.lib.msu.edu/projects/ssb/display.cfm?TitleID=463&Format=jpg (accessed April 14, 2011). Coleman Campbell 27 Hamilton, James. Life in Earnest, or, Christian Activity and Ardour. Philadelphia: American Sunday-School Union, 1845. in Shaping the Values of Youth: Sunday School Books in 19th Century America. http://digital.lib.msu.edu/projects/ssb/display.cfm?TitleID=489&Format=jpg (accessed April 12, 2011). James, John Angell. The Young Man From Home. London: Religious Tract Society, 184?. in Shaping the Values of Youth: Sunday School Books in 19th Century America. http://digital.lib.msu.edu/projects/ssb/display.cfm?TitleID=578&Format=jpg (accessed April 12, 2011). Kenny Carle's Uniform. Boston: American Tract Society, 1863. in Shaping the Values of Youth: Sunday School Books in 19th Century America. http://digital.lib.msu.edu/projects/ssb/display.cfm?TitleID=524&Format=jpg (accessed May 12, 2011). Magie, David. The Spring-Time of Life, or, Advice to Youth. New York: American Tract Society, 1855. in Shaping the Values of Youth: Sunday School Books in 19th Century America. http://digital.lib.msu.edu/projects/ssb/display.cfm?TitleID=498&Format=jpg (accessed April 12, 2011). Newnham, William. Man, in His Physical Intellectual, Social, and Moral Relations. Philadelphia, VA: American Sunday-School Union, 1847. in Shaping the Values of Youth: Sunday School Books in 19th Century America. http://digital.lib.msu.edu/projects/ssb/display.cfm?TitleID=552&Format=jpg (accessed April 13, 2011). Coleman Campbell 28 Palmer, Lynde. Helps Over Hard Places: Stories for Boys. Boston: American Tract Society, 1862. in Shaping the Values of Youth: Sunday School Books in 19th Century America. http://digital.lib.msu.edu/projects/ssb/display.cfm?TitleID=451&Format=jpg (accessed April 12, 2011). Wise, Daniel. The Young Man's Counsellor, or, Sketches and Illustrations of the Duties and Dangers of Young Men. New York: Carlton & Phillips, 1853. in Shaping the Values of Youth: Sunday School Books in 19th Century America. http://digital.lib.msu.edu/projects/ssb/display.cfm?TitleID=488&Format=jpg (accessed April 12, 2011). Secondary Sources: Boylan, Anne M. Sunday School: The Formation of an American Institution, 1790-1880. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1988. Douglas, Ann. The Feminization of American Culture. New York: Avon Books, 1978. Hall, Donald, ed., Muscular Christianity: Embodying the Victorian Age. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994. Kimmel, Michael. Manhood in America: A Cultural History. New York: The Free Press, 1996. Ladd, Tony and James A. Mathisen. Muscular Christianity: Evangelical Protestants and the Development of American Sport. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books, 1999. Putney, Clifford. Muscular Christianity: Manhood and Sports in Protestant America, 1880-1920. Cambridge & London: Harvard University Press, 2001. Rachman, Stephen. “Introduction.” Shaping the Values of Youth: Sunday School Books in Coleman Campbell 29 19th Century America. http://digital.lib.msu.edu/projects/ssb/?action=introessay. Scott Macleod, Anne. A Moral Tale: Children's Fiction and American Culture, 1820- 1860. Hamden, CT: Archon Books, 1975. Winn, William E. Tom Brown's Schooldays and the Development of “Muscular Christianity.” ATLA Religion Database. http://web.ebscohost.com/ehost/detail? sid=1a4bf82d-e360-4b7e-ae9a88e217cfbb81%40sessionmgr112&vid=1&hid=105&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3 QtbGl2ZSZzY29wZT1zaXRl#db=rfh&AN=ATLA0000668609 (accessed March 25, 2011). Tertiary Sources: Merriam-Webster Dictionary. “Muscular Christianity.” http://www.webster-dictionary.net/definition/Muscular%20Christianity PBS. “The Civil War: A Film by Ken Burns, Fact Page.” http://www.pbs.org/civilwar/war/facts.html