Being A SpeciAl AdviSer T h e U n i t

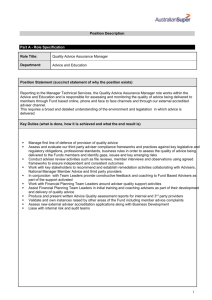

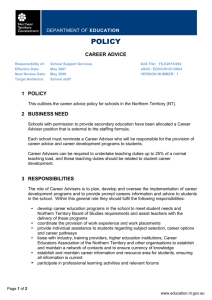

advertisement