IN EUROPEAN REGIONAL GOVERNMENT C O U N T R I E S

advertisement

REGIONAL GOVERNMENT IN EUROPEAN

COUNTRIES

Report commissioned by The Constitution Unit

University Colleqe London

John Hopkins

Faculty of Law

University of Sheffield

ABSTRACT

The following r e p o r t begins by giving brief descriptions of regional

government in six member s t a t e s of t h e E.U.. Accompanying each is a general

commentary on t h e i r history a n d development. The second section of t h e

r e p o r t focuses on t h e relevance t h e s e examples of regionalism have t o any

f u t u r e developments in t h e U.K., specifically England.

I t is my opinion, t h a t regional governments can aid democracy t h r o u g h

decentralisation of t h e central state. European regions a r e evidence of t h i s .

However, it is not clear from t h e English proposals what t h e actual purpose

of t h e region is t o be. Regions a r e a method of government, suitable for t h e

achievement of certain goals. These goals must f i r s t be clearly established

before any discussion of s t r u c t u r e o r form can t a k e place. The English

proposals seem t o have emerged from a need t o answer t h e "West Lothian

Question", raised i n relation t o Scotland. This they can never do and t h e

example of Spain, which is often given a s t h e model for s u c h a solution , in

fact emphasises its inadequacies.

English regionalism if it is established for t h e purposes of decentralisation

must t r u l y decentralise power from t h e centre. Failure t o do s o w i l l leave t h e

regions without a role and with little rationale. This was t h e case in Italy.

They must also be endowed with s i g n s c a n t financial autonomy t o allow t h e i r

meaningful operation independent of t h e state. These two criteria will allow

regions t o develop policies independently from t h e centre, more suitable t o

wishes of t h e regional electorate. I t is f a r from clear, however, whether a

Westminster government would be willing t o tolerate s u c h divergence of policy

within England. If it cannot, t h e n t h e r e seems no rationale, i n my opinion, for

t h e regional level.

Introduction

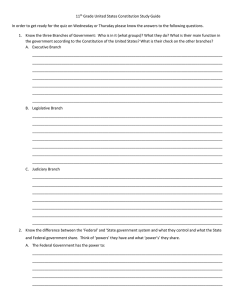

Part I

1.1

Belgium

1.2

France

1.3

Germany

1.4

Italy

1.5

Portugal

1.6

Spain

Part I1

Regional Government in Europe

-

Lessons for the U .K.

11.1

The Functional Role of European Regions

11.2

Regional Finance

11.3

Regions a s units of Democratic Renewal

11.4

The West Lothian Question

11.5

Implementation Procedure

11.6

Conclusion

INTRODUCTION

Over t h e l a s t f i f t y years, Europe has seen a burgeoning of federal or

regional systems of government, y e t t h e U.K. has remained unitary.

In fact

b y 1995, t h e U.K. is t h e only large s t a t e in t h e E.U. not to operate a regional

Debate over regional government is not new t o Britain, b u t it has

level.

generally been restricted to t h e Celtic periphery.

However, t h e Labour

Party's recent proposals have now placed t h e issue on t h e English political

agenda.

The following report examines t h e experiences of six European

regional governments in t h e light of t h e debate in t h e U.K..

There a r e two p a r t s t o t h e report.

Firstly, a brief description of the

regional s t r u c t u r e s in t h e six countries examined (Belgium, France, Germany,

Italy and Portugal).

t

These a r e each accompanied by a general commentary.

The second p a r t examines some particular i s s u e s of regional government on a

Europe wide basis.

By necessity, t h i s work is r a t h e r subjective in its choice of subject

matter.

Time has limited my analysis t o those a r e a s which I feel have '

relevance t o t h e

U.K.'s

debate.

For this reason, t h e content of

commentaries varies from country t o country.

identical s t y l e in t h e basic descriptions.

I have attempted to use an

The need for this subjective

approach is due t o t h e nature of regional government a s a subject.

who s t u d y

11

regional governments

the

a r e often

Those

asked t o comment on their

success" or failure b u t t h i s misunderstands t h e concept.

If a scholar

comparing t h e governance of Britain and France, t h e question "was Britain a

success" would be meaningless.

The variables involved make t h e operation of

t h e country

dependent on

much

more than

government.

This is also t r u e of regions.

the

s t r u c t u r e s of

national

I t is an impossible (and pointless)

t a s k t o define regional success o r failure without looking a t specific policies

i n great depth.

I am no scholar of health manaaement or education, so for

t h i s reason I r e s t r i c t myself to t h e possible benefits of regional government

i n general government terms.

t

There a r e actually eleven "regional" systems, of various t y p e s , within

t h e E.U .. These six were chosen for t h e i r similarity in size t o the U . K . .

The exceptions t o t h e l a t t e r a r e Belgium and Portugal, but their

interesting characteristics, make them worthy of mention.

PART I

The financial portions of

, ,

t h e following descriptions use standard

terminology in t h i s field, a s w e l l as some typologies used in my own work.

To aid t h e reader, these a r e clarified below.

Regional taxation r e f e r s t o taxes collected i n t h e region where the

individual region controls tax rates.

These do not include taxes collected by

t h e region or taxes shared o u t between levels if t h e centre retains control

over their r a t e and application.

Block funding includes taxation raised in t h e region or shared between

levels b u t controlled nationally.

This is because t h e region has no control

over t h e yield and must rely on changes a t t h e national level to increase or

decrease it. In practice these taxes a r e a specific t y p e of block funding, less

open

to

national

nonetheless.

interference

,c-\

.

?

than

grants,

but

nationally

controlled

a

The --latter t y---p e of-----taxes can be divided into two f u r t h e r categories. ,

-.-Ceded taxes a r e those granted t o regions within their own territories. Shared

taxes a r e those shared

between

levels and

equalisation between individual regions.

may involve

a

degree of

All figures a r e 1992 unless stated

other wise.

1-1

BELGIUM

Geoqraphic Information

No.

-

3 Regions (Brussels, Flanders, Wallonia)

3 Communities (Flemish, French, German)

(non contiguous boundaries)

Population

-

(Regions)

Population

-

(Communities)

Brussels

0.96 Million

Flanders

5.77 Million

Wallonia

3.26 MiUion

Figures not readily available and difficult to calculate

Flemish

6.25 Million (approx)

French

3.40 Million (approx)

German

Size

-

(Regions Only)

Brussels

0.07 Million

161 km2

Flanders

13,522 km'

Wallonia

16,844 km2

Structure

Deliberative Bodies

Each Region or Community possesses a parliament (or council) consisting of

between 25 and 124 members (Regional Councils vary between 75 and 118).

The Flemish Community and Flanders Region have amalgamated their s t r u c t u r e s

and their assemblies a r e now known collectively a s t h e Flemish Council. Even

in Wallonia where t h e French and Walloon Councils remain separate, t h e same

representatives sit in t h e two chambers, (although t h e Brussels members only

sit on t h e Community Council).

The Brussels representatives t o t h e Flemish

Council have t h e s t a t u s of non-voting observers on regional matters.

Executives

The executives of these bodies a r e limited under t h e Constitution t o t h e

following maximum numbers. A l l a r e elected by and from t h e relevant council.

Region/Community

Maximum Executive Size

Flemish Region/Community

11

Walloon Region

7

Brussels Region

5

French Community

4

German Community

3

Status

Belgium is a federal state and a s s u c h t h e Regions and Communities a r e equal

t o t h e national level. Together, they comprise t h e highest tier of government.

,

Inter-Governmentdl Relations

Local Government

Regions have competence over local government supervision and may exercise

s u c h power within t h e limits of the constitution.

Certain powers a r e

guaranteed and local government continues t o receive t h e bulk of its finance

from local taxation and central grants. The s t r u c t u r e may not be altered by

t h e Region but due to t h e regions' extensive legislative role, local government

can b e severely effected by regional policy decisions.

There a r e some

linguistic exceptions t o t h i s such a s the German speaking communes, which a r e

supervised directly by t h e federal authorities.

Central Government

Unlike many other federations, t h e equality of s t a t u s enjoyed by t h e Regions

.

and Communities is practical a s well a s theoretical.

Regional decrees (or ,

ordinances in Brussels) a r e equal to federal laws.

When such decisions

--- /

overlap and both have been passed legally

(which in theory should rarely

occur), t h e problem wiU go t o arbitration, a function of t h e Federal Senate.

-

_ __-

-=

-

...

-.

Second Chamber

A s with most federations t h e Belgian parliament includes second chamber- to

.-------- *--

r e p r e s e n t t h e federal units.

Of t h e total composition of seventy one, forty

-- members a r e directly elected from t h e relevant language a r e a s (25 Flemish and

15 French), twenty one a r e appointed by t h e Communities (10 Flemish, 10

French and 1 German) with a final ten being indirectly elected by t h e

senators of t h e major language groups ( 6 Flemish and 4 French).

The role of this body is mainly advisory, except in issues of linguistic

legislation, constitutional amendments, international relations and changes to

the Belgian state structure. In all other matters t h e Senate may delay, amend

and propose legislation b u t t h e final say always Lies with t h e Chamber of

Representatives.

I t s primary role lies in t h e area of resolving conflicts of

- ..--..

. .

i n t e r e s t between federal units (including t h e federation itself).

When such

conflicts arise, t h e senate must focus on compromise a s any agreement wjll

..--

- .

need t h e co-operation of a l l parties.

Reqional Institutions

There a r e no

separate

regional s t r u c t u r e s , (although some police

are

administered locally). The extent of regional legislative power means t h a t t h e

legal regime in one Region/Community can differ from t h a t in another.

I t is my understanding t h a t t h e regions operate separate civil services b u t

I have been unable to confirm this.

Functional Powers

Culture & Educabon

Social Functions

Economic Functions

Economic development

Education (c)

Health (c)

I

Conservation

Sport ( c )

Environmental

Language Policy (c)

(not nuclear or rates)

Protection

(limited in ~ e r m a n )

Employment

Water

Libraries (c)

Agriculture

Help for disabled (c)

Museums (c)

Spatial planning

Child care &

Regional culture and

protection (c)

languaue ( c )

Public works

,?

r-

Energy

-

1

I

Transport

(not rail or air)

(c)

-

Community function

A l l competences a r e legislative though in many areas the federation retains a

supervisory role in co-ordination s t r u c t u r e s across Belgium.

These a r e

restricted t o an absolute minimum and include school leaving ages and

minimum degree standards. In general t h e Regions undertake economic p o k y

while t h e Communities deal with "personal" matters. The federation remains

responsible f o r a r e a s in which a national approach is deemed desirable. These

include Defence, Police; 1Monetary a n d Fiscal policy,

Security.

R a i l transport and Social

I..

International relations is divided between t h e Regions/Communities

and t h e Federation according t o domestic functions.

Financial Resources

others ~ 1 . m

Hcrrowlng C14.

sllecr

rIC Grants

FeulonaI Taxes

Ceded Tax=

~4.6%)

C1.m

(9 .a%)

Fund (my

Regional Taxes

-

Environmental Taxes

Ceded Taxes

-

Gambling and betting tax

(Regional unless

Tax on gambling machines

stated other wise)

Tax on licensed premises

C 67

Inheritance tax

Real estate tax

Property sales tax

Road tax

T.V. & Radio licences (Communities)

An optional regional surcharge may be added to these taxes.

'

-

I ncorne Tax C16.5

sorrwlna C1.9161

Others C 2 0 . 5 % )

V.A.T.

Ceded Taxes

C 2.4961

L

Community Finance (French)

Block Funds

-

Income tax (Regions and communities)

V.A.T. (Communities only)

(shared taxes)

A basic equalisation mechanism (included in t h e income tax share) works

between Regions and t h e Federation dependent on their tax base.

The

Communities have no such scheme a s their V.A.T. share is awarded per capita.

Specific Funds

-

Minimal

specific

funds

for

employment

programmes.

Corn mentar Y

The development of t h e Belgian regional system is rooted in t h e

language divisions t h a t divide t h e country.

A s a unitary state. Belgium was

always an unlikely entity, straddling the ancient language divide of Europe

a s it does.

For centuries, t h e romance and germanic languages have met

along a border which dissects modern Belgium. When the Belgian state was

established in 1830, principally by French speakers in Brussels, this cultural

fact was ignored and a unitary s t a t e was established. The language divisions ,,

within t h e country were f u r t h e r exacerbated by the addition of several

German speaking areas after t h e first world war. From t h i s period onwards,

existing tensions within t h e country steadily intensified. First, t h e extension

of suffrage gave t h e majority Flemish control over the national parliament,

which they used to end discrimination against their language and establish a

language border in 1963.

However, t h e Walloons (French speakers of t h e

south) now felt their economic interests were being ignored by t h e Flemish.

Wallonia, a s one of t h e f i r s t areas of Europe to industrialise, faced serious

economic problems by t h e 1960's. Flanders, in contrast had been largely

agricultural until much later allowing it to expand into newer industries, less

susceptible to t h e recessions of t h e 1970's and 80's (Thomas, 1990). Quite

naturally, t h e Flemish a r e very liberal in economic views while t h e Walloons

traditionally favour left-wing proto-Keynesian policies.

The result of these problems were t h e riots and disturbances of t h e

1970's. Some predicted a very dark f u t u r e for Belgium b u t happily these

doomsday predictions were wrong. That they proved inaccurate is d u e largely ,

t o t h e innovative and complex system of regionalism t h a t now exists in t h e

country.

There a r e a few important points t h a t should be noted in relation to t h e

Belgian conundrum.

Firstly, t h e vast majority of Belgians (of all cultural

groups) do not favour t h e independence of their region.

There is a

widespread (and justifiable) view t h a t s m a l l "independent" s t a t e s of Wallonia

and Flanders would be vulnerable to domination by France and t h e

Netherlands respectively.

The Belgian regions have t h u s more t o lose by

splitting entirely, than they have t o gain.

Secondly, t h e devolutionist

aspirations of t h e individual regions differ markedly.

Despite their majority

in t h e Belgian parliament, t h e Flemish continue t o fear language domination,

due to t h e s t r e n g t h of t h e French language a s a whole.

The Flemish

complaint has t h u s been based on cultural issues. The Walloons, despite their

1

minority s t a t u s do not fear language discrimination but instead call for

economic policies in their region

which differ fundamentalk from those

expressed by the Flemish. Their claims were t h u s based on economic matters.

Finally, t h e German speakers wished a degree of control over their own

affairs, principally in cultural matters.

The claims from all t h r e e language

groups prompted one Belgian Prime Minister t o describe Belgium a s "a happy

country composed of t h r e e oppressed minorities" (Swan, 1988).

To answer

. these varied wishes and t h e problem of Brussels a unique system of dual

regionalism was devised.

The t h r e e Regions and t h r e e Communities comprise, with t h e federal

level, t h e highest level of government in Belgium.

Unique t o t h e Belgian

federation, t h e regional units a r e not contiguous and in some cases have

authority over overlapping

territories.

. -

This occurs because t h e Communities

and Regions a r e responsible for different a r e a s of policy and in theory a t

least their constituencies a r e di££erent.

Regions a r e territorially based

authorities while t h e Community represents t h e individuals who a r e part of it.

A t least i n legal terms neither unit is superior t o t h e other. The Communities

were established ,'1970 t o implement t h e policy of "cultural autonomy"

(Alen A

"& Ergec R, 1990, p10) mostly t o appease t h e Flemish majorities' fears.

, ,,

The

concept of "cultural autonomy" was subsequently extendedL-to "community

autonomy"

a s these units became responsible f o r "personalised"

issues.

Broadly speaking this comprises large areas of social policy such a s Health

and Education a s well a s more "minor" policies, s u c h a s s p o r t and heritage.

The Flemish speakers, French speakers and German speakers make up ,

these t h r e e Communities.

In practice t h e two largest Communities cover

Flanders and Wallonia respectively.

Brussels is divided between t h e French

and Flemish while t h e German Community covers a small area in t h e east of

t h e Walloon region.

f

The regions, also established in 1970, were introduced mainly to satisfy

t h e interests of t h e Walloon minority.

The Walloons (though not t h e French

speakers of Brussels) feared t h e policies of t h e majority Flemish government

discriminated against their traditional industries and wished to pursue their

own strategy.

To satisfy this demand, t h e Regions were assigned authority

over large

areas of economic

_ _ _ .. --. policy, though not monetary and fiscal matters.

The distinction between Community and Region has lessened over time.

I

Flanders and t h e Flemish Community have amalgamated and French Community

and Walloon Regional Councillors, a r e the same individuals (delegates from

Brussels sitting in t h e French Council).

There can be little doubt t h a t t h e regional s t r u c t u r e in Belgium has

achieved its immediate aim.

J

The fact t h a t t h e.'x still is a Belgium is evidence

I

1

of this. There a r e enough links between t h e varied Belgian peoples (the royal

family, a common social security system and t h e football team t o name b u t

t

A good map of this s t r u c t u r e is included in

el mar ti no's chapter.

t h r e e ) t o e n s u r e t h a t t h e state w i l l continue.

The regions, in t u r n , have

given a feeling of security t o t h e "oppressed minorities" t h a t allows the

frustrations t h a t threatened t h e peaceful co-existence of t h e people in this

a r e a of Europe t o be vented t h r o u g h t h e decentralised s t r u c t u r e .

There is

certainly a feeling among some Belgians t h a t they avoided a potential Bosnia.

For this, t h e new s t a t e s t r u c t u r e must take credit.

However, t h e ability of

t h e regions t o actually deliver policies different from t h e previous unitary

s t a t e is not quite a s clear.

The WaUoons hoped t h a t t h e creation of t h e economic regions would

allow them to a d d r e s s their economic difficulties more effectively. In practice,

t h e Socialist dominated Walloon region finally abandoned its policies of state

intervention in 1985.

These had been followed contrary t o t h e national

government's wishes. The national centre-right government was certainly the

winner in t h i s battle.

However, was t h e failure of Wallonia's proto-Keynesian

policy d u e to t h e policy itself o r t h e regional s t r u c t u r e it operated within?

Covell has argued t h a t t h e latter certainly played a part. Her view has been

t h a t t h e t y p e of economic devolution granted t o t h e Regions meant the ,

Regional government was always unlikely t o succeed in operating such a

markedly different policy from t h e centre. This was due to a lack of financial

resources which prohibited a co-ordinated

policy on any

workable scale,

combined with t h e fragmentation of control between t h e Regional and national

levels (Covell, M, 1986, p274).

Since then, t h e economic policy pursued by

t h e Regions and t h e Federal level has been strikingly similar.

T h i s trend is

something Covell has also noted in t h e Canadian federal system.

Since her

s t u d y in 1986, t h e final two phases of Belgian federalisation have been

completed and wider economic powers (notably in t h e major "national" sectors

originally reserved by t h e centre) a r e now available t o t h e regions.

Whether

t h i s now makes them capable of pursuing a policy contrary t o t h e national

one, is a moot point but a s t h e regional tier collectively accounts f o r around_

. of total government expenditure (excluding loan repayments etc.) such a

half

case could be argued.

The by word of Belgian federalism is co-operation. More than any other

regionalised state, t h e regional t i e r s must negotiate with t h e federal level and

vice versa (Deelen, 1994). This is due principally to t h e equal s t a t u s of laws

passed by t h e d a e r e n t tiers of government and t h e impossibility of dividina

competences between regions so they do not overlap. One example in Belgium,

is t h e continuing role of t h e national level in

regulating

immigration.

-

Although this field would seem t o be of no interest to t h e regions, t h e fact

t h a t Community competences include t h e integration of such people into

Belgian society, means they w i l l foot a proportion of t h e bill caused by t h e

national decision.

The importance of co-operation is emphasised in t h e

situation a s r e g a r d s t h e European Union.

When t h e Council of Ministers meets, t h e Belgian delegation is likely t o

consist of - representatives

of more than one level. When a policy area is

-- . . _ _

. __ _ _

exclusively regional, t h e delegation w i l l comprise regional representatives only,

______-1.1-1-

If t h e issue under discussion is shared

with t h e chief delegate alternating.

ministers will sit with t h e Federal

- - - - - -... -- -minister. In these cases, t h e chief delegate w i l l depend onirole each level

-- 6.

plays. If t h e Federal government t a k e s t h e primary role (eg. transport) t h e n

between levels, t h e Regional/Community

-

.

--

..r.-,IY-

*-d%-_IL

I

this minister w i l l take t h e position. Importantly, despite these musical chairs,

t h e position presented, w i l l still be "Belgian",

advance.

agreed by t h e ministers in

Again, the Belgian system although allowing strong regional

influence forces co-operation on t h e parties concerned.

The result of t h i s

reliance could be a lack of accountability t o t h e regional electorate.

prospect is examined in more detail below, in relation to Germany.

1-22

FRANCE

Geoqraphic Information

No.

-

22 R6gions

(including Corsica)

Population

Size

-

-

Average

2.35 Million

Smallest

0.74 Million

Largest

10.66 Million

Average

24,000 k m2

Smallest

8,280 k m2

Largest

45,348 k m2

(Corsica)

(Ile de France)

(~lsace)

(Rhone-Alpes)

This

I

-

Structure

Deliberative Bodies

-Two Chambers.

One directly elected primary chamber of between 31 and 1 9 7

seats. T h i s chamber is styled t h e " ~ e g i o n dCouncil" except in Corsica where

it is given t h e title of "Assembly".

A second, Economic and Social Chamber,

>

-

-- - - ----

acts in an advisory capacity, in tandem with t h e directly elected assembly.

This is appointed from trade union, professional and employer oruanisations.

Executive

Officially, t h e President elected from t h e Council, is t h e only executive.

In

practice, the bureau of t h e President, consisting of a number of councillors

acts a s a Regional "cabinet".

The vice-presidents of t h i s bureau a r e allocated

specific responsibilities.

Status

Created under ordinary statute.

a form of local government.

No constitutional protection.

-

The region is

-

Inter-Govern mental Relations

-.

~ o c a lGovernment

Regional government is not superior t o other forms of local government.

has no involvement in their structure, supervision or finance.

It

Although t h e

regions a r e not superior, regional policy in land use and economic planning

will restrict DGparternent options. Financial support for Dgpartemental projects

may be withheld if t h e regional priorities a r e not addressed.

Central Govt.

Central government does not exercise an a priori tutelle. Restrictions on

regional policy

a r e limited to

breaches of

law.

These can delay t h e

implementation of a regional decision but t h e final arbiter is the administrative

court. The Regional Prefect remains t h e national representative in t h e region.

They operate t h e post facto tutelle as well a s r u n n i n g most deconcentrated

s t a t e services.

National Policy Involvement

Regions have no official i n p u t into national policy

Resional Institutions

Civil Service

-

Regional officers belong t o t h e "territorial service".

T h i s service covers all those civil s e r v a n t s working

f o r local government.

Members of t h e territorial

service may transfer t o t h e s t a t e service and viceversa.

Functional Powers

Regions have no legislative power but may d i r e c t policy (within varying

constraints) on t h e following matters.

Few regional functions a r e carried out

without t h e involvement of other t i e r s of authority.

Economic

Social

Culture & Education

Regional economic

plan

Spatial planning

(approval of local

plans)

Secondary education

infrastructure

Economic aid

Regional parks

Professional

education

Regional railways

Regional transport

schemes

Regional airports

1

Universities

I

I

I

1

Inland waterways

Research

1

I

I

I

)I

'

I

II

11

I

I

I

I

Tourism

Regions also possess a general

competence t o act, unless another level

- of government has exclusive competence.

The broad interpretation of t h i s

concept h a s allowed Regions t o operate in a r e a s not originally envisac~edb y

t h e central state. The s t a t e h a s recognised some of t h e s e activities in s t a t u t e

(e.g. universities).

1

Financial Resources

Regional Taxes

-

Car registration fee

Property tax

Land tax

Business tax

Residence tax

Regional

-

Surcharges

Borrowing

House sale registration tax

Driving Licences

-

No borrowing restrictions

except on loans above

certain level (outlined in national s t a t u t e )

,

-

Block Funds

V.A.T. reimbursement (for tax incurred by regional

authority )

Grant for

cost

of

decentralised

services

(index

linked)

Specific Funds

-

Professional education Grant

Educational i n f r a s t r u c t u r e g r a n t

Commentary

The development of regiondlism i n France has a long and t o r t u r e d

history. Since t h e revolution, t h e concept of a decentralised France has been

debated between those of t h e Jacobin (centralist) and Girondin (decentralised)

b u t it is only in t h e last fifteen years t h a t t h e l a t t e r view has prevailed.

Nevertheless, during t h i s brief period t h e pace of change has been quite

remarkable, considering t h e traditional opposition t o s u c h concepts amongst

t h e French elites.

Since t h e formation of t h e French s t a t e in t h e sixteenth century, its

r u l e r s have wished for a high degree of control over t h e area within t h e i r

This applied a s much t o t h e ancien regime a s it did t o t h e republican

realm.

The only difference was t h a t t h e latter were immeasurably

era.

successful.

more

The highly centrdlised s t a t e envisaged by t h e Jacobins, was

f u r t h e r enhanced by Napoleon who created t h e Prefectural system, much

copied

by

centralist

regimes

in

other

countries.

This

handed

the

administration of local affairs handed over t o an official, appointed by Paris,

who presided over an artificial c o n s t r u c t , ( t h e Dgpartement).

This had a s

little in common with t h e previous loyalties of t h e populace a s possible.

In

France, t h e legend s u g g e s t s t h a t boundaries were drawn on t h e principle t h a t

t h e Prefect should be able t o ride from his seat of administration to t h e

Dgpartemental boundary and back in a single day (though in some areas, one

s u s p e c t s his horse would have died of exhaustion).

The highly centralised s t r u c t u r e of sub-national government i n France

continued relatively unchanged for t h e best p a r t of two centuries.

This had

much t o do with t h e success of t h e national authorities in imposing their

c u l t u r e on t h e population of France (around half the population did not s p e a k

,

French a t t h e time of t h e revolution), a model again duplicated across the

globe.

Yet despite their best efforts, regional sentiments remained, most

notably in Corsica, Breton and t h e regions of Occitania.

By t h e t u r n of the

c e n t u r y movements defending regional culture and languages were achieving

greater popularity (Beer, 1980).

I t was economic changes in t h e 1960's t h a t laid t h e foundations for the

subsequent reforms. Regional leaders began t o organise into lobb yinu bodies

incorporating

businessmen,

representatives.

trade

unionists,

politicians

and

other

In response t o this, t h e government created centrally

appointed advisory bodies (C.O.D.E.R.), primarily a s a method of controlling

t h e s e "forces vivres" movement (Keating, 1983). This was followed i n 1972, by

indirectly appointed Regional Councils in 1972 a n d a Regional Prefect to

ad minister certain functions now handled regionally.

Most notably t h e new

Regional Prefect completed t h e regional portion of t h e national plan.

In all

cases, t h e "democratic" element in t h e regions acted only i n a n advisory

capacity.

The growth of regional movements throughout France a n d t h e worsening ,

violence in Corsica encouraged t h e left

- t o incorporate democratic regions as

p a r t of their programme for government.

The lack of control over the

existing regional bodies and t h e feeling t h a t their economic- planning

had been

incompetent led t o widespread s u p p o r t f o r t h e i r democratisation. By creating

t h e regions, t h e central government had recognised t h a t s u c h a level should

exist b u t they had no plausible excuse f o r t h e lack of reaional accountability.

When these regional bodies encouraged economic developments opposed by the

local populace (such a s t h e commercialisation of areas of t h e Mediterranean

coast) t h e resentment and perceived need for democratic control was increased

(Keating & Hainsworth, 1983). The insensitivity of t h e central government to

certain regional issues also helped - t h e mood for reform

Corsican rail network)

.

(eg. closing the

Indeed Boisvert has suggested t h a t s u c h blunders

committed by t h e centre a r e inevitable in a centralised regime today, leading

inexorably t o calls for greater local and regional autonomy (Boisvert, 1988).

The left capitalised on these views and incorporated many regional movements

into t h e new P.S..

The success of t h i s new party in 1981 e n s u r e d t h a t

France's history of centralised government would change.

The plans of t h e French Socialists encompassed a broad programme of

decentralisation t h e most radical of which was t h e creation of a tier of

democratic regions with special s t a t u s f o r Corsica. A t t h e h e a r t of t h e project

was t h e creation of democratic Regional Councils a s t h e representative bodies

This body would gain control over a r e a s of government

of t h e region.

previously handled nationally or b y national appointees a n d not by local

governments.

The

sectors transferred

to

the

regions

(and

to

local

governments) were intended t o be self standing "sectors" o r easily definable

a r e a s of them.

For instance, education was t o be divided between all levels.

The maintenance and construction of schools was to be handled by local

governments, while t h e national tier was responsible f o r curriculum, staff

salaries and universities.

Within local government Communes

were given

control of primary, D g p a r t e m e n ts, secondary and Regions, lyckes.

However,

although t h i s division was relatively strzigrht.forward in education, in other

a r e a s t h e divisions proved more dif5cult to define.

In parallel

drastically.

with

t h e s e reforms, t h e

role of t h e

p r e f e c t changed

Firstly, t h e concept of t h e tuteLle was removed from all levels of

local government.

This had previously given t h e Prefect t h e ability t o veto

local decisions on policy grounds.

In t h e Region, t h e Prefect was replaced by

t h e elected Regional President (of t h e Council) a s t h e executive body.

The

Regional Prefects' new role was t o head t h e nationally r u n services in t h e

Region and a c t a s a post-facto constitutional watchdog over t h e decisions of

t h e Council a n d its organs.

Implementation of t h i s reform was remarkably swift, considering its

controversial and radical nature, b u t this was a deliberate policy of t h e

programme's architect, Gaston Defferre.

H e reasoned t h a t t h e formidable

opponents t o t h e reforms should not be given time t o r e - s r o u p a f t e r their

defeat in t h e general election.

Furthermore, t h e r e were enough opponents

within his own r a n k s t o cause trouble, should t h e 0pportunit.y arise.

opposition came from t h e "notables".

Most

These political magnates hold power

t h o u g h t h e cumrrl des mandates system used in t h e French Republic.

This

J

allows one person to simultaneously hold several senior elected posts from

local t o European level.

These powerful individuals could lose power in a n y

decentralisation package especially if t h e DGpartement (their power base) lost

out t o t h e new Regions. Their influence originated from t h e i r ability to fight

f o r local i s s u e s in t h e national arena.

If t h e local/regional councils could

achieve this, their influence would diminish.

To buy off t h e bulk of these

opponents, t h e reform of t h e cumul system was watered down (Schmidt, 1990).

Many other areas of t h e policy saw compromises and t h e final legislation

left many regionalist disappointed with t h e outcome (Kofman, 1985). This was

nevertheless, t h e b e s t Defferre felt he could achieve.

Further criticisms

surrounded some of t h e technical aspects of t h e laws. Their speedy passage

saw minor flaws enshrined in t h e law a s well a s controversy over t h e exact

division of powers. Again, Defferre had realised t h i s and specifically made the

laws vague a n d a

---

mere framework, which could be altered later.

The

important i s s u e f o r Deffere was t o pass t h e basic legislation t o s e t up t h e

regions ( t h e most controversial p a r t of his proposals). In this he succeeded

where countless previous attempts had failed.

Ironically, t h e actual establishment of t h e Regional Councils took until

1985

a s t h e Socialists kept delaying t h e election date.

--.I ,._.

because t h e i r mid-term

This was primarily

unpopularity was likely lead to a poor result in t h e

regional elections.

In fact it was disastrous, with only two of t h e twenty one

mainland regions

returning

P.S.

majorities.

The previously

vocif~rous

opponents of t h e regional reforms now claimed they were being implemented

too slowly. The only significant regio2al reform t h e right actually introd~~cec!,

when t h e y r e t u r n e d t o power, was t o give t h e Commi5sa'res de la R P - ~ u b l i c

( t h e Socialists' new title for Prefect) their old title back (Keating, 1983).

In practice, t h e operation of French Regions has differed somewhat from

original intentions.

The major economic rationale for t h e region had been

their involvement i n t h e national economic planning. The abandonment of t h i s

programme was potentially a serious problem for t h e new reqions.

In fact, i t

merely led t o a shift of emphasis, away from direct investment and towards

encouragement of public/private infrastructural projects, t h e encouragement

of inward investment and loan guarantees for t h e improvement of businesses.

The ability of t h e regions t o undertake t h i s role, relies largely on their

independence of finance.

Since around 80% of regional f u n d s a r e f r e e to be

s p e n t according t o regional priorities this i s not a problem.

However, a s

regions account f o r l e s s than 2% of government spending, their financial

muscle is Limited t o s a y t h e least.

This means t h e reuions must fulfil a co-

ordinatinq role, u s i n ~st.3t.e ;ind lrlcal aovelrnment finance a s well a s n r i v a t p

e n t e r p r i s e t o e n s u r e t h e development of t h e reaion.

One evamrle of this lies

in their role i n constructing regional t r a n s ~ n r t networks, based larcr~lv

around t h e networks of S.N.C.F., which t h e regions harle allthoritv over (with

t h e exception of t r u n k routes).

The reqion has uiven a natural focus for t h e

development of local i n f r a s t r u c t u r e s beyond t h e

without needing national organisation.

regions' role in France.

Dgpartemental level, vet

This latter example is indicative of t h e

A s Michel Rocard said in 1982;

I1

Dans la domaine economiql~e,l a 1-4aion exerce. en principe une funrtion

d e pilote" (Le Monde. 1982)

Overall, t h e regions a r e widely regarded a s a success in Frznce, despite

- - .--

t h e i r financial irrelevance.

Opinion polls suggest t h a t most French wish t h e

regions t o exercise more power and regard them a s t h e qovernment of t h e

Why have French regions received t h i s popularity?

f u t u r e ( ~ r e h l e r ,1992).

Firstly, their role

in education is perceived a s a success, almost without

-_-.C_."l.--

exception.

Despite inheriting a neglected education i n f r a s t r u c t u r e in danger

of collapse under increasing s t u d e n t numbers, t h e regions

revitalise it t h r o u g h innovative investment and tax rises.

were able to

I n t h e latter case

t h e population of most regional electorates, whatever their political complexion

were

willing

t o accept

such

educational s t r u c t u r e .

increases, a s long a s t h e y

The obvious link between t h e

maintenance of t h e lycges may have helped t h i s process.

were for t h e

regions and t h e

F u r t h e r success has

been seen in their a p p a r e n t t.h r --..i f t . With t h e exception of t h e i r much criticised

investment in new assembly buildinus, (ironically, to increase t h e i r profile) t h e ,

regions have been efficient in t h e i r use of public f l ~ n d s . Fureaucracies a r e

small and direct running of projects is r a r e . Instead, reaional initiatives a r e

commonly

undertaken

through

joint

boards,

chaired

by

the

reaional

representatives b u t representing local government and private business.

1-3

--

G -E

.R MA

.- N Y

.-

No.

-

1 6 Lander

Population

-

Average

4.9

Million

Lo west.

0.7

Million (Bremen)

Highest

16.7

Averaae

212.312 km-

Size

-

Smallest

Lar crest.

Million (N. Rhine- Westphalia)

1

404 k m ? (Bremen!

9

70,552 k m - f B a l f e ~ i ? \

Structure

--Deliberative

Bodies

/:.

Each Lander 1s f r e e t o decide on i t s own system of parliamentarv a n v e r n m ~ n t . :

a s outlined in their constitution.

In practice, all opted f o r a sinale chamber

assembly, with t h e exception of Bavaria which has a bi-earnera! system.

-Executive

This is also outlined in t h e respective regional constitutions, b u t cabinets

generally comprise between nine

a n d fifteen ministers. The cabinet is directly

.....

responsible t o t h e regional parliament.

A s p a r t of a federal system, t h e Lander a r e p a r t of t h e highest t i e r o f ,

government.. This equality is partly theoretical, however, a s t h e principle of

Bundesrecht bricht Landesrecht u n d e r p i n s t h e constitution

o v e r r i d e s Land law).

( ~ e d e - a 1 lab7

The distribution of potrers is intended t o keec s u c h

conflicts t o a minimum.

I_nerTGo-vernm.eq&l

Relations

Local government is entirely u n d e r t h e control of regional government.

t h i s reason

its s t r u c t u r e varies extensively

between

Lander.

For

National

governments' involvement in Local government affairs is severely restricted.

Central

Government

-----. ..There is no institutionalised

government.

central

government

control

over

regional

National Policy I n v o l v e m g ~ t

The second chamber of t h e German parliament ( ~ u n d e s r a t )is appointed

.

entirely -by

t h e regional governments.

.-

This body plays an important role in

German policy making, including a veto o v e r s t a t u t e s affecting L a n d e r r i u h t s .

Redondl I n s t i t u t i o n s

Regional Banks

-

Each L Z n d e r h a s a regional hank. Representatives of

each sit on t h e board of t h e B u n d e s b a n k .

Regional Civil

-

Each region 0 p e r a t . e ~its own civil s e r v i c e .

-

The role of government r e p r e s e n t a t i v e s i n Germany

Service

Government

Ofices

is merely t o a c t a s a conduit between t h e national

a n d regional levels.

There a r e no national field

services, with t h e exception of t h e Post Office and

t h e Deutsche Bahn.

Police

-

Each region possesses an independent police force

(Bavaria also controls its own b o r d e r police).

is no national force.

Lesal System

-

-

.,

There

.

T h e extensirre n a t u r e of recrional cclmpetences e n s u r e s

differences of lecral regime b e t w ~ e nr e a i o n s .

Legal S t r u c t u r e

-

The c o u r t s t r u c t u r e is entirely r e a i o n a l k e d . with a

final

tier

of

appeal

constitutional

and

courts

operating a t t h e federal level.

Powers

Unlike other regional systems, t h e r e is no definitive list of regional functions.

The constitution gives regions

powers, not specifically allocated t o

federation ( t h e famous subsidiarity clause).

education, c u l t u r a l affairs a n d

local

the

In practice t h i s means police,

government

a r e exclusive

reqional

competences.

In

all o t h e r

a r e a s , t h e L a n d e r a r e responsible f o r

administration of national policy (only limited b y leqal restrictions).

the

I n most

a r e a s of domestic policy t h e r e f o r e a c u l t u r e of co-operation is n e c e s s a r y .

Financial Resources

1

I

1

German Regional Finance (1991)

Regional taxes

-

Local sovernment taxes which a r c r u e t o t h e citv

s t a t e s only.

Ceded taxes

-

P r o p e r t y tax

I n h e r i t a n c e tax

Vehicle tax

Beer tax

Shared taxes

-

Income tax (50%)

Corporation tax (50%)

V.A.T. (35%)

Professional tax (7.5%\

Funds f o r Eastern Lander

Specific f u n d s

-

Restricted f u n d s f o r capital investment

Grants f o r i n f r a - s t r u c t u r a l improvement in Eastern

Lander

Borrowing

-

There

are

no

national

restrictions

on

regional

borrowing

Commentary

The p r e s e n t German s t r u c t u r e d a t e s from t h e post-war constitution of

1948, however German regionalism h a s a much longer history.

Since its

inception i n 1864 a n d with t h e exception of t h e period 1933 t o 1948, Germany

has always o p e r a t e d a regionalised s t r u c t u r e .

Nevertheless, t h e c0nstit~l.t-ion

of 1948 saw many differences on t h o s e t h a t had qone before. Primary amongst ,

t h e s e differences was t h e dismemberment of P r u s s i a into several smaller s t a t e s

a n d t h e creation of regional u n i t s with limited regional identities.

exceptions t o t h i s were Bremen, Hamburg a n d Bavaria.

The

Surprisinqly, t h e

creation of t h e s e artificial regions led t o a wide discrepancy i n size a n d

population.

The constitution did give mechanisms for t h e reform of t h e

territorial divisions, b u t a p a r t from a few minor a d j u s t m e n t s t h e boundaries

have remained c o n s t a n t . The constitutional amendment of 1976 which removed

t h e B u n d r s d u t y t o initiate reform of L a n d e r boundaries in t h e Light of

economic realities a n d replaced it with a voluntary ability .to do s o effectively

removed t h e i s s u e from t h e political agenda.

I t is now almost inconceivable

t h a t t h e regional boundaries will be reformed.

The permanence of t h e p r e s e n t s t a t e of affairs is quite remarkable in

considering t.he situation in t h e 1950s. Opinjon ~011si.n t.hi.5 n ~ r - i o d fou17d a

distinct lack of s u p p o r t for t h e federal s t a t e s (Co!s. 1 9 7 5 ) .

However, since

t h i s time, popular s u p p o r t has r i s e n steadilv a n 6 t h n n r s . s ~ n t _S V S ~ S T has

become firmly established in t h e minds of t h e electorate.

T h e allies' purpose in encouranina t h e new C e r m a r !

strl.lct.l.ire

was t o

divide sovereignty between c e n t r e a n d reqion t o e n s u r e no sinqle aovernment

could accumulate enough power t o r e p e a t t h e e v e n t s of 1933. This Averican

concept was not entirely forced upon t h e German delegation at t h e London

conference a n d in most a r e a s , t h e Basic Law reflected t h e preferences of t h e

regional presidents themselves (Johnson. 1990).

I n f a c t t h e German federal system h a s not

led t .o a- clean division of

--legislative authority between levels.

-A s with all o t h e r attempts at. federalism.

- .

t h e overlappinu of functions h a s led t o t h e blurrinq of t h e boundaries

between regional

a n d national

authority.

In

Germany, t h e position

exacerbated by t h e question of "concurrent

powers".

.

. __-----

is

These extensive Dowers,

listed u n d e r Article 74 of t h e Basic Law allow t h e L a n d e r to legislate until t h e

B u n d exercises its r i g h t t o do so.

However, t h e German constitutional c o u r t

h a s been unwilling t o involve itself in t h i s a r e a , instead seeina this a s a

political decision.

Furthermore, once t h e B u n d h a s "occupied t h e field" t h e

L a n d e r a r e excluded from f u r t h e r participation (Blair, 1981).

This leaves

regional legislative powers primarily in t h e a r e a s of education,

.

police. and local

-government.

The weak legislative position of German regions is often overlooked a n d

is often assumed t h a t t h e i r impressive s t a t u s comes from t h i s s o u r c e . A s we

have seen, however, t h i s is not t h e case. Regional power in Germany is based

upon two other a r e a s of authority.

-

Firstly, t h e extensive executive

power.

-,--

afforded t o t h e L a n d e r a n d secondly t h e i r authority in t h e B u n d e s r a t o r

German Senate.

Under German constitutional law, t h e national government is forbidden

from operating field s e r v i c e s in all b u t a few specific areas, namely:

Foreign affairs

Federal finance a d ministration

Federal Railways

Federal Post Office

Armed Forces (Article 87, Basic Law)

In all other a r e a s , t h e L a n d e r exercise executive authority. The ability

of

t h e national

government

to

supervise this

authority

is

limited. - - h y

constitutional restrictions. In most cases, t h e s u p e r v i s o r y provisions must he

made by law and receive t h e consent of t h e B u n d e s r a t . In practice t h e r e f o r e ,

t h e regions must collectively a g r e e t o them. I n most areas. t h e federal s t a t u t e

l a y s o u t t h e policy (often after B u n d e s r a t approval) which t h e reqions must

t h e n implement according t o law.

t h e regional executives.

The methods of implementation a r e left t o

,

Executive autonomy, could b e a v e r y weak freedom f o r t h e German

regions were it n o t f o r t h e i r protection t h r o u g h t h e ~ u n d e s r a t . This b o d y ,

comprising r e p r e s e n t a t i v e s of t h e German L a n d e r h a s taken on a n importance

p e r h a p s not envisaged by t h e framers of t h e Basic Law.

B u n d e s r a t must qive its consent t o laws which

of t h e reaions.

Under t h i s , t h e

I

f f e c t t h e interest.? o r d l ~ t i e s

The Sander- i n t e r p r e t e d t h e concept of i n t e r e s t broadly.

In

a s e r i e s of cases, t h e Federal Constitution31 Court azve its hlessincr t.n t h i s

approach a n d t h u s e n s u r e d a L a n d e r veto o v e r many a r e a s of policv.

It h a s

been t h i s power t h a t h a s allowed t h e recrions t o retain power i n t h n fapa nf

many centralising p r o c e s s e s (Blair, 1981, p71).

I,L.. :

One f u r t h e r a s p e c t of t h i s veto power h a s been t h e entrenchment of cooperative federalism.

This s e e s decisions t a k e n increasing'b y LBnder a c t i n g

t o t h e B u n d , a s t h e basis f o r

collectively a n d p r e s e n t i n g a "position"

-

.

This means regional opinions a r e likely t o g e t compromised in

negotiations.

t h e "national" L a n d e r position, leading t o a reduction in regional autonomy,

a n d a n increase i n t h e power of regional elites. This problem h a s been raised

by Bulmer who n o t e s t h e lack of accountability c a u s e d b y t h i s i n c r e a s e i n coMore famously, Scharpf's discussion of

operative p r o c e d u r e s (Bulmer, 1990).

a n d continued operation of joint cot h i s t r e n d pointed t o t h e inefficiency

-- .

operative bodies e v e n when t a s k h a s been completed a s t h e administrative

mechanisms had become e n t r e n c h e d . P e r h a p s most worrying of all, t h e L a n d e r

parliaments have

become increasing

irrelevant

.

.

t o these

inter-executive

......

discussions, often being placed with a £zit accomnli (Scharnf. 1992).

Despite, Germany's f e d e r a l n a t u r e a n d its obvious differences with t h e

4'

U . K . , some of its experiences a r e relevant t o t h e d e b a t e in Enu!=lnd,

Regional

devolution has b r o u g h t new problems of accountability and democracy. These

a r e not insurmountable, b u t must be recognised if a successful s t r u c t u r e is

to be achieved. Any system which involves more t h a n one level of qovernment

(and t h i s includes t h e U . K . t o d a y ) w i l l by definition involve inter-level

bar gaining.

The

parliamentary/councS

importantly, openness.

important

point.

involvement

is

in

the

to

accept

process

this

and

and

ensure

perhaps

most

I t is t h e lack of t h e s e mechanisms which h a v e led t o

t h e democratic difficulties facing Germany today. Nevertheless, one should not

g e t carried away i n criticism of t h e German struct.ure.

seems t o

have delivered

a n economic

miracle.

The

I t is popular a n d

power of

reqional

governments t o a d d r e s s reaional i s s u e s is s u b s t a n t i a l and i n ~ o n t . r a s tw i t h

France or Italy has a p p a r e n t l v m3de

3

differen~e.

No.

-

20 regioni

(15 o r d i n a r y r e g i o n s )

( 5 special r e g i o n s )

Population

-

Average

Lowest

Size

-

2,887,381

115,996

Highest

5,853.902

Average

15,063 kmL

Smallest

3,262 km!

Largest

25,708 k m 2

Valle d'Aost-a

Czm~3ni?!

Structure

Deliberative Bodies

A single r e g i o n d council (of between 30 t o 80 members) is t h e lesislative body

of t h e region.

Executive

-.--- -- . ..A Giunta is elected from t h e regional counril i2 each reqion.

Sizes a r e

outlined i n t h e reqional s t a t u t e s according to nnpulation.

-S

-.-t.-a..t--u-s..

Italian regions a r e inferior t o t h e national level, b u t t h 5 regions do enjoy a

d e g r e e of constitutional protection.

Special Regions each have an individual

constitutiorlally protected, s t a t u t e which outlines t h e i r powers and operation.

Ordinary r e g i o n s also have s e p a r a t e c o n s t i t u ~ o n a ldocuments, althouqh t h e i r

powers a r e identical a n d t h e i r constitutions a r e founded in o r d i n a r y law.

I n t e r -Govern mental Relations

A l l local government (provincial and corn munal) comes u n d e r t h e supervision

of t h e regional a u t h o r i t i e s t h r o u g h t h e Regional Control omm mission.

comprises e x p e r t s appointed b y t h e regional council.

This

A s t h e commission only

a s s e s s e s t h e xlegality of a c t s , t h e members a r e predominantly j u r i s t s a n d civil

-

servants.

Central government no l o n a e r o n e r a t e s an a priori tutelle Qver tho Tt?lian

regions.

I n s t e a d . t h e s t a t e a ~ p o i n t e d reaional cnm mjs.s.inner

regional council t o r e c o ~ s i d e ra orrc.sosal.

The commiscinner

n : ? ~ 2 . ~ 1 a~

t5er! ! ~ b m i t

s u c h a proposal t o t h e constit1rtional court., s h o u l d he Or :he

seil! feel it. is

illegal. If it r a i s e s a potential conflict of i n t e r e s t (with another region or t h e

,

c e n t r a l government) it may be submitted t o parliament b u t t h i s process h a s

n e v e r been used.

Influence on_National Policy

Although t h e second chamber of t h e Italian Parliament

was intended t o

r e p r e s e n t territorial cleavages, its direct election makes it part- of t h e national

political scheme a n d of little importance t o t h e regions.

national policy

Presidents.

is i n s t e a d

directed t h r o u q h

the

Regional influence on

Conference of

F.egional

This body is of5cially recognisec? b y t h e government and is

especially importance

when t r e a t i e s or Eur0pe.n.

leuislat_i.r?n affectinu t h e

regions a r e i.inder discuscion.

More formalised l i n k s exist betweon t h Presidents

~

of t.hs snsci?! r e -!or.

and

t h e c e n t r a l a o v e r ~ r n e n t , T h e v b a v ~t h e r-iqht t o speak i n c a b i n . ~ tv5pn i z ~ ~ o s

of importance t o t h e i r reqions a r p d i s r ~ ? s . s e d .T

vote i n s u c h meetinas.

~ Firiliqn

P

P r e s i r ? = n + m a v even

In practice. t h i s privileqe is rare!:?

enforced.

Ott.~?r

formal powers include t h e r i u h t of all reuions t o place bills before t h e national

parliament.

In practice, however, s u c h approaches a r e r a r e l y fruit.ful.

Regional Institutions

-

civil Service

A s e ~ a r a t ecivil service o n e r a t e s i n each of t h e t w p n t l t

reqions.

Pav a n d conditions a r e see nationallv hilt a r e net

connected

with t h e s t a t e clvil s e r v i c e .

Staff

mot.ilitv

between national a n d regional s e r v i c e s is possible and

manaaed centrally.

Government

-

A Regional Commissioner sits i n each region.

H i s main role

is t o oversee t h e operation of t h e regional authority and

Offices

a c t a s Liaison between them a n d c e n t r a l government.

-

Police

There a r e no resional police f o r c e s , b u t local police a r e

u n d e r t h e a u t h o r i t y of t h e region.

-

Legal

Structure

The lecral s t r u c t u r e is u n i f o r ~throl!qhout Italy. with t h e

~ x c e p t i n ncf Sicily, where a s e p q r a t e hiuh

ccllrt.

o~erates.

Powers

I(

I(

Economic

Economic planning

Ij

II

Employment

]

Spatial planning

Environmental

protection

Social assistance

Tourism

ji

Transport

/

I

Education (Sicily)

,

Regional languages

(special regions only) I!

I

iI

i

I1

!

I

i

i

I

i

powers

passed a t t h e national level.

which a r e limited

ii

ii

II

The o r d i n a r y regions enjoy no exclusive legislative a v t h o r i t y .

exercise "concurrent"

I/

I

I

.i

11

II

I!

I

(

I

I

i/

Museums 6 Libraries

I

I

I n d u s t r y & commerce

Culture & Education

1

Health

I

Electricity

II

II

1

1

1

I

I

11 Agriculture

Ii

(

Social

1

Public works

II

I

Iii

II

ii

11

ii

I!

Instead t.hev

b y framework

legislation

In addition, some leaislation outside t h e s e areas

is passed b y t h e national parliament. t o which t h e reqions a r e empowered t o

a d d t h e i r own specific amendments.

Special regions h a v e exc11lsive leaislative auth0rit.y i n all f h e a r e a s Listed

__

---_.

above (with t h e excention nf inl=lnr! waterwavs and electricitv). C.;nsti+-utional

wrangling has r e s t r i c t e d t h e Speci.el r e a i o n s i n t h e exercise of t h e i r a!ithol-itv.

Loans C 9 . 5 M

I

I

Italian "Ordinary" Region Finance (1987)

Financial

Resources

----- -. -.Regional Taxes Ceded Taxes

Circulation tax (electricity & gas)

- Motor vehicle tax

Tax on s t a t e concessions

Tax of' regional concessions

Tax on u s e of public land

Health s e r v i c e contrihutions

Block f u n d s

- Block a r a n t from central aovernment

29

Specfic funds

-

Finance dllocated t o pay f o r specific services e g . transport.

a n d health.

1

I

I

1

1

II

I

I

I

I

x)

Loans C 5 .

Spec I f I c Funds C 3 5 .2%J

Taxes

t Block G r a n t s ( 5 5 . 1 % )

Italian Special Region Finance (1987)

Cpmwntary

..

The development of regional government in t h e Italian s t a t e d a t e s from

t h e establishment of t h e second republic, a f t e r World War Two. Prior t o t h i s ,

Italy had been ruled by a unitary s t r u c t u r e based on t h e constitution of

Piedmont. This was despite s t r o n g regional identities within t h e Italy, caused

in p a r t by its late establishment.

I t must not be forgott& t h a t until 1870,

Italy was nothing more t h a n a geographical expression.

The "unification"

which was achieved a t t h i s d a t e was really t h e expansion of Piedmontese

power throughout t h e peninsular and those who favoured a federal o r region

s t r u c t u r e f o r t h e new s t a t e were unsuccessful.

B y 1945, a t t i t u d e s had changed.

I t was generally accepted, as in

Germany, t h a t decentralisation would protect t h e fledgling republic from a

repeat of 1921.

An important p a r t of t h i s division of sovereignty was to be

t h e institution of a regional level.

In f a c t reaional government was already

i1

i n existence in much of t h e c o u n t r y . The resistance, who were administering

t h e country, organised themselves regionally.

state,

peripheral

areas

such

as

governments independently of Rome.

Sicily

More seriously for the unitary

and

Sardinia

were

operating

The s t r e n g t h of regional identities in

t h e s e areas meant some feared t h e y would opt for secession.

I n response t o this situation, t h e new constitution allowed for t h e

immediate establishment of "special regions" in those peripheral areas where

regional identities were particularly strong. In 1 9 4 8 individual statutes were

negotiated between t h e Italian s t a t e and Sicily, Sardinia, Valle dlAosta and

Trentino-Alto Adige (althouqh-

Sicily had already been granted a special

.

status

s t a t u t e in 1946). In 1963 Fruili Venezia Giulia was also g r a ~ t e d special

---

and i n 1 9 7 1 , Trentino-Alto ~ d i g ewas divided into two autonomous provinces.

i

The two autonomous provinces undertake most resional res~onsibilities.

The wider development of reqions t h r o u s h o u t t h e country was not to

occur until t h e *1970's.

---

The delay was caused primarily by t h e opposition of

those political parties in power t o any dilution of their authority. During t h e

negotiations for t h e

post-war

constitution, t h e Christian Democrats

had ,

championed t h e regional cause, while t h e left had been much more sceptical.

However, t h e unexpected victory of t h e centre-right in t h e first 'elections

changed their stance.

Unwilling t o decentralise po wer from the central

institutions which they controlled, t h e government constantly postponed

implementing t h e legislation necessary for the "ordinary regions1' to become

'

reality (Evans, 1977). Furthermore t h e success of t h e left in local elections

made t h e right even less Likely t o devolve power to Communist controlled

regions, in a "red belt" a c r o s s t h e country.

U n s u p r i s i n f f l ~t,h e left's (and

particularly t h e Com munists') initial. scepticism chansed t o s u ~ ~ o when

r t they

realised their exclusion a t t h e national level had become entrenched b u t their

power in individual reaions remained verv s t r o n a .

Ev t h e 1970's t h chance

~

to exercise power a t a resional level looked v e r v enticina ( Z a r i s k i . I Q87, ~ 1 0 5 1 .

The sta1emat.e was broken b y t h e "o~c?ni.ncrto t.he left1' of t4e 1960's.

This

brief

experiment in

consensus

politics

led

to

t h e long

overdue

establishment of "ordinary regions" in 1 9 7 0 , although t h e extensive reforms

of seven years later changed t h e i r operation markedly.

t

The decision to

The German speaking Tyrolese argued, with some justification t h a t t h e

artificially constructed region (with an Italian majority) did not protect

their interests and was being used t o continue a policv of discrimination

towards them.

.

'

establish a regional s t r u c t u r e produced

"Messianic"

hones amonqst many

Italians (Leonardi, Nanetti and Putnam, 1981, p103) b u t t h e s e were not t o be

fulfilled.

Those a r g u i n g for regional government highlighted t h e need for

/

decentralisation in an over centralised bureaucratic. t h e regional diversity

/i

within t h e country and t h e need for t h e democratisation of many services.

In practice, t h e national government saw regionalisation having only one

purpose, t o democratise t h e planning process.

This led t o t h e granting of

minimal regional authority in most areas and led one commentator to liken them

to "giant municipdlities", though endowed with legislative powers (Giannini,

1984). The lack of authority granted t o regions was f u r t h e r affected by t h e

failure of local government reform to accompany t h e regional legislation.

This

.

--

led t o an inevitable overlapping of functions and rivalries between all levels

of local government, looking t o maximise t h e i r powers (Cassesse and Torchia.

The modern svstem of Italian regions was finally

in 1977.

----_ established

-._ _.

. In t h i s year, t h e Presidential 616 gave a large swathe of powers to t h e

.add

i'

regions, allowing them, a t least. in theory, t o undertake policy outwith t h e ,

control of t h e centre. This differentiates them from t h e local ffovernment

units which a r e not seen a s units of policy

administration.

making, b u t r a t h e r

local

The a r e a s granted to regions a r e listed above but t h e ability

of regions t o actually undertake policy in t h e s e a r e a s is still open t o debate.

Ordinary Regions a r e subject t o framework laws which can be very s t r i c t i n

t h e leeway t h e y g r a n t t o t h e regional level.

/

This has led ,ko Sanantonio t o

conclude t h a t t h e regions suffer from a distinct lack of autonomy.

In t h e

area of health he a r g u e s t h a t t h e national ministry, t h r o u g h these framework

powers, has actually "increased and regained" powers theoretically lost to

regional o r local levels (Sanantonio, 1987). This analysis would be supported

by Hine who described Italian regionalisdion as, "merely ...t h e devolution of

t h e ad ministration of central1y -deter mined policies" (Hine, 1993).

The legislative restrictions of t h e ItaLian reniorls a r e compounded hs.

their

financial

weakness.

Althollffh they

anzcount for

~ r o ~ l n 20%

d

qf

government expenditure, very Little of this 1s f r e e for reqions

- -. t o spend ( E n a e l

& Ginderachter, 1993).

In 1987. nearlv 82% of ordinary recrional e ~ ~ e n d i t i ~ r - e

was allocated t o specific areas b y t h e central uovernment.

Althouah 1 1 . ~ p 9 ~ i a ! "

regions were in a much better situation, relyinq on specified a r a n t s for ~ q l v

39% of expenditure, voluntary nature of t h e h v ~ o t h e c a t e d a r a n t s means

regions must follow national policies o r risk serious financial difficulties

(Cassese & Torckia. 1993). Much depends

on these qrants.

The

OF

t h e restrictions t h e centre places

f

opposing

vieci

h.as

been

expressed

hv

L e o r ~ r d i . whr? has

consistentlv a r g u e d th=rt t h o Italian reuiqns have heen a dvnamic force in

Italian economics. H i s work on Emilia-Romaana a r a u e s t h a t innovatjve r@crion?l

policies in t h e s p h e r e s of economics and environment in particular have been

responsible for t h e success of t h e region (Leonardi & Nanetb, 1991).

With s u c h divergent opinions on t h e Italian regions it is di££iclilt

to

come t o any s y n t h e s i s on their overall operation. There a r e nevertheless some

comments t h a t can be made.

Firstly, few doubt t h a t t h e Italian state has

t r e a t e d the regions a s i r r i t a n t s r a t h e r than democratic partners.

The s t a t e

h a s attempted t o l i m i t t h e role of regions by several means, notably financial

b u t also by bypassing them and granting powers t o local authorities directly.

This prima-facie s u p p o r t for local democracy obscures t h e centre's ulterior

motive which recognises t h a t local governments a r e less able t o resist q r a n t s

i n aid p r e s s u r e s t h a n a r e t h e regions.

The r e s u l t was t i g h t e r control of

policy rather t h a n decentralisation. The centre's attempts t o restrict reaional ,

action has meant that. regions have relied on ingenuity t o achieve any po1i.c~

autonomy.

T h i s h a s been aided b y t h e powers devolved t o t h e reuions in

1977, which althoush believed t o be irrelevant a t t h e time, have t u r n e d out

t o be of vital importance. (notably professional education and spakia! plannj.nq)

(Cassesse and Torchia, 1993: Leonardi, Nanetti & Putnam, 1981). Overdl, any

regional "success" has been achieved in suite of t h e central aovernment not

because of it.

P O R-T

-- U G A L

No.

-

2 Autonomous F.eqions

Population

-

A znres

236.709

Mzidei1-3

353,045

1991 saw t h e reform of t h e It.alian reainnal finance scheme. The new

scheme g r a n t s Health Service contributions t o t h e reqion. In ~ r a - t i c e

this c h a n a e s little except for e n s u r i n a more stable finance than when

regions relv on government g r a n t s .

-

Size

2,334 krn2

Azores

759 km2

Madeira

Madeira possesses a sinale, directlv elected. leaislative council.

The A z o r s c

has a bi-camera1 system, with t h e second chamber r e p r e s e n t i n q individu?!

islands.

This a d v i s o r y chamber ( f u r t h e r powers can be delegated to it) i s

appointed by t h e island executives, although elected councillors may also

a t t e n d a s non-voting observers.

Executive

Officially, executive authority lies i n t h e Minister of t h e Republic, a central

government appointee.

In practice, t h e Regional President, elected from t h e ,

regional parliament u n d e r t a k e s t h i s role.

H e o r s h e appoints t h e regional

cabinet a n d r u n s most executive functions.

St a tus

.-

The Portuguese regions are guaranteed b y t h e naticnal constitution but re~*!-!

inferior t o t h e national level.

which cannot b e altered

Each possess a seosrate constit_uti~r.s!st.at.ute

~rithoilt t h e conse~-it of t h e individual reaional

government.

1nter:Gove-r_n-mental

Relations

Local

Government

--. .- - .- -. ..-.- - -. . -..

-

Local government is supervised b y t h e regional t i e r .

Basic legislatior! on

finance and orqanisation is dealt with nationallv.

Central Government.

T h e r e is no c e n t r a l aovernment r o n t r o l , h!.it the Minister of t h e Republic mav

delay regional legislation.

To o v e r t u r n s u c h a decision r e q u i r e s a n overall

b..

majority of the' regional assembly .

Natlo-nal Pglic y_ Influence

T h e r e is no institutionalised mechanism f o r t h e elected reaional r e p r e s e n t a t i v e s

t o influence t h e nat-ional sovernment..

Nevertheless. the Ministers (sf t h e

Republic a r e Cabinet Ministers a n d a r e eunectsd t o r e ~ r e s e n treaiona! oninior:

a n d i n t e r e s t s i n Cabinet d i s c u s s i a ~

s.

Regional Civil

-

Each region h a s a n i n d e ~ e n d a n tcivil service.

Mlrlimum