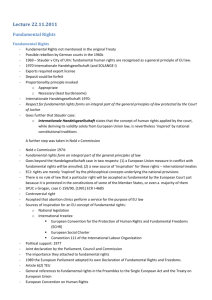

Whitehall and the Human Rights Act 1998

advertisement