Document 12262527

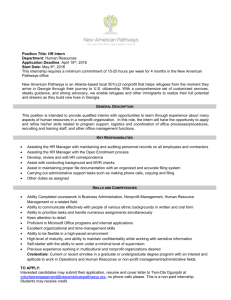

advertisement