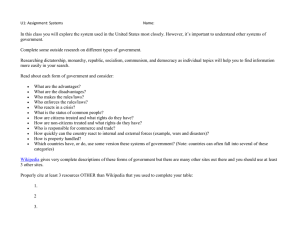

of Non-citizens The Rights

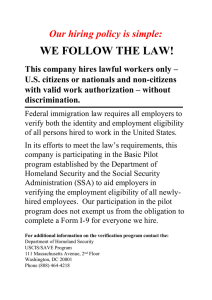

advertisement