ENGL 346 ENGL 231, 234, 245, 371 (Jane Eyre), 365

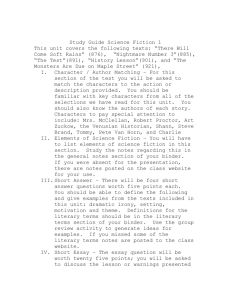

advertisement

The following courses fulfill the LCI (Literatures, Cultures, Identities) requirement: ENGL 346 (Jane Eyre), 365 The following courses fulfill the pre-1800 requirement: ENGL 231, 234, 245, 371 English 327 and 328 require a permission code for enrollment. Please see Laura Krughoff for ENGL 327 and William Kupinse for ENGL 328. English 212: The Craft of Literature: The Fire of Imagination Beverly Conner This course provides an introduction for non-majors to the craft of writing fiction and poetry. It asks the crucial question of how do writers bring the imagination to the page, and what is their motivation? In other words, we will consider the artistic choices writers make to create an aesthetic literary experience, a fictional world. What is the role of courage in exploring the imagination? Where do fact and fiction intersect? We will read and critique fiction and poetry, using texts as our foundation, asking where the fire ignites, when the comet appears? Because the course is designed for non-majors, no previous experience in creative writing or literary analysis is required, but expect to do both. English 212B: The Craft of Literature: Comics as History Alison Walker This fine arts course introduces scholarly methodologies and theories used to critically engage with comic books and graphic novels as pop culture artifacts. This class specifically opens up the medium’s complexity and encourages students to critique and analyze diverse material exploring how comic books and graphic novels represent history and the past. Because the field of Comic Studies is, by definition, cross-disciplinary, our class reaches across the humanities to investigate issues of history, art, literature, and culture. Ultimately, we will examine how comics function as a medium as well as what these comic books reveal about the ways that we represent the past. ENG 212: The Craft of Literature Allen Jones This course provides an introduction for non-majors to the craft of literature, engaging both critical and creative faculties. Studying and practicing methods of aesthetic and formal analysis of literary texts, students will consider the artistic choices writers make to create an imaginative experience. Students will also have the opportunity to participate in the creative process. English 220: Introduction to English Studies Alison Tracy Hale English 220 is the required “gateway” or introductory course to the English major. Whether you consider yourself a cultural critic, literary scholar, or creative writer, this is the course that provides you with hands-on work in the college-level “discipline” of English Studies. We’ll focus on developing the essential tools—practical and intellectual—that will allow you to thrive in your future courses and well beyond. Expect to read a lot (poems, short stories, a Shakespeare play)--and write a lot (analytical papers, exercises, and at least a little creative work). In addition to the practical dimensions of the course, we’ll spend some time thinking, talking, and writing about what it means to study English, and to attend carefully to language and form, in an era characterized by an obsession with “new media” and preoccupied with text messages, tweets, and Instagram. We’ll read and hone your skills on works that are “classic” and traditional, and apply them to contemporary texts, including, perhaps, Claudia Rankine’s formally experimental Citizen—which meditates on the racial aggressions of 21st-century America—and Alena Graedon’s The Word Exchange (2014), a “bibliothriller” that pits technology against the enduring power of the written word. English 220: Introduction to English Studies Darcy Irvin English 220 is an introductory course designed to prepare you for the survey and upper division special topics classes. Rather than focus on literature from a specific period or genre, we'll instead read a wide variety of texts in order to help us understand literature as a field of study. What constitutes a work of literature? Who decides which texts are "literary"? What does literature do? What kinds of reading practices do we employ in order to study literary texts? Through class discussion, argumentative essays, and creative assignments you will become acquainted with the reading and writing skills we use in literary analysis and interpretation. Authors in this course may include Italo Calvino, Margaret Atwood, Roberto Bolaño, Emily Dickinson, Agha Shahid Ali, Djuna Barnes, Haruki Murakami, and James Baldwin. English 227: Introduction to Fiction Writing Suzanne Warren When asked for advice on starting a band, Blondie singer Debbie Harry replied, "Learn to play your instruments, then get sexy." This class is all about mastering the basics before you can get sexy: the mechanics of plot, character, point of view, timeline, setting, and tone. We learn them by reading a lot, including stories by Junot Díaz, Flannery O'Connor, and Sherman Alexie, and writing a lot: flash fictions, reading reflections, short stories, exercises. Coursework includes 3-4 short stories, 1-2 flash fictions, a writing notebook, workshops, and reading, reading, reading. English 227: Introduction to Fiction Writing Ann Putnam In this course you will write two 5-6 page stories, one Short Short and one Deep Revision, in addition to keeping a writer’s log and reading lots of short stories. You will have many opportunities to participate in panels, small group workshops, large group workshops, as well as many in-class writing sessions. Each day when you come to class you will know exactly what to expect, but you will also be surprised. So you'll need to be here every day--ready to do things you've never done before, remember things you've never remembered before, ready to write about things you didn't know you knew. All you need is a brave and willing heart. English 231: British Literature and Culture: Medieval to Renaissance John Wesley Covering almost ten centuries, this course will introduce you to the literature written in Britain from the Anglo-Saxon invasion to the aftermath of the English Civil War, from the earliest texts written in the English language to the drama of William Shakespeare and the epic poetry of John Milton. The emphasis throughout will be on developing skills for textual analysis while at the same gaining a critical appreciation for the relationship between literature and its historical or cultural contexts. In our case, this will mean touching on the cultural transformations of Britain from the Christianization of its early Germanic invaders to the religious and political revolutions of the seventeenth century, noting especially the causes and consequences of the Protestant Reformation. The course itself is divided into three sections, each of which focuses on a particular theme (I. Heroes and Monsters, II. Voice and Incarnation, and III. Inner Lives). The provisional reading list for Fall 2015 includes: Beowulf, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, Canterbury Tales (selections), The Second Shepherd’s Play, The Faerie Queene (selections), Doctor Faustus, Twelfth Night, Paradise Lost (selections), and selected lyric poetry (Sidney, Shakespeare, Donne). English 233: British Literature III Darcy Irvin This survey course covers British Literature from the beginning of Queen Victoria's reign in 1837 up through the present. Together, we will examine a wide range of literature from the last two centuries, from novels and short stories, to poetry, drama, and prose. Beginning with the nineteenth century, we will pay close attention to how the Industrial Revolution radically shaped emerging political, cultural, and social views. From new ideas about the role of women or human evolution, to emerging technologies and industrial production, how did Victorians grapple with a rapidly changing, modern world? And how did they represent that world, the British Empire, and themselves, in the literature they produced? Turning our attention to the twentieth century, we will continue to press on issues of modernity. Reacting to the perceived conventionality of the Victorians, how did writers before, during, and after the two World Wars respond to the massive political and social upheavals they faced? And how are contemporary writers today continuing to embrace modernity as it emerges in new forms? Authors in this course may include Dickens, Gaskell, Conrad, Wilde, Yeats, Joyce, Woolf, Achebe, and Smith. English 234: American Literature and Culture: Colonial to Early National Alison Tracy Hale This course introduces you to essential texts and contexts for American (U.S.) literature from its origins in European travel writing and Native American oral traditions through colonization, revolution, and the social, political, and economic transformations of the end of the 18 th Century. Focused on the shifting notions of community and the different bases for inclusion and exclusion, the course takes a comparative look at the ways in which populations interacted across the space now known as the United States, and emphasizes the ways in which those interactions produced new forms of identity and community—often at the expense of previous models or the exclusion of certain peoples. Expect to read “classic” texts of early America (Bradstreet, Rowlandson, Franklin, Paine) and some that are less familiar and that come from communities and perspectives outside of the Anglo-American canonical tradition. Course requirements include short writing assignments, a 5-6 page paper, midterm, and final exam. This course counts toward the department’s pre-1800 requirement. English 235: American Literature and Culture: The Long 19th Century Tiffany MacBain A Department of English "Works, Cultures, Traditions" course, ENGL235 offers an overview of American literature of the long 19th century. Representing a variety of perspectives, the texts under study engage imaginatively and critically with developments in American politics, letters, and culture. The result is a literature that is "distinctly American" in its subject matter and approach. Areas of study include Native- and Anglo-American relations; the U.S.-Mexico borderlands; slavery, abolitionism, and Reconstruction; the frontier myth; and the immigrant experience. English 245: Shakespeare: From Script to Stage Denise Despres In June of 1997, the new Globe Theater opened on the bank of the Thames; today, hundreds of playgoers from every nation attend historically reconstructed productions of the plays of William Shakespeare. The early-modern Globe, as modern audiences discover, was minimalist: while stage properties might include a few sumptuous costumes (bought second hand), there was no scenery and few props, for audiences depended upon the poet’s language to create and sustain theatrical illusion. Playwrights were first and foremost poets. Thus, students who think of William Shakespeare as the superlative writer prominently featured in British Literature courses have not been misled, since Shakespeare’s poetry and dramatic scripts were presented for reading as early as the compilation of the First Folio of 1623. For centuries, Shakespeare’s plays were read aloud by devotees who did not necessarily patronize the theater, despite the fact that the extant folio pages of his “scripts” are just that—play scripts that were written down only to benefit the players. The affection most of us feel for particular characters or stories in Shakespeare’s dramatic canon are most likely a result of the experience of a powerful performance. Individual productions and stellar performances, however, are rooted in careful readings and interpretations of Shakespeare’s scripts, whose language reflects the social and cultural concerns current in late Elizabethan England. If Shakespeare is now a world author whose works seem to transcend class, race, and national boundaries, he is so because the writers and artists who translate his plays, like theatrical dramaturges, begin with scripts and figure out how to make them accessible. English 327: Advanced Fiction Writing Laura Krughoff In this advanced fiction workshop, we will consider what it means for a writer to develop a body of work. While we will continue to practice and hone the fundamental skills and techniques used in narrative prose, the expectation in this course will be that you are ready to produce complete works of short fiction and are beginning to explore your own voice, aesthetic, subjects, and themes as a writer. To this end, our work will be two-fold: we will read selections from seven collections of short fiction to examine how important contemporary American short story writers pursue particular themes, return to and re-examine various topics, and develop a recognizable style or aesthetic. You will simultaneously produce a total of six works of original fiction, and the semester will culminate in a portfolio that curates your best work augmented by an artist’s statement that illuminates why you have chosen the stories you have and what the portfolio reveals about your own body of work. This course is, obviously, reading and writing intensive. A great deal is going to be asked of you. It is my hope that by dint of the hard work you will put in over this semester, each one of you will grow as a reader and a writer, as a thinker and a critic, and, most importantly, as an artist with a vision. English 346: Jane Eyre and Its Afterlives Priti Joshi Since it first appeared in 1847, Charlotte Brontë's Jane Eyre has spawned considerable controversy and numerous revisions in which it has reappeared in a variety of guises and disguises. Examining texts that draw on aspects of the “Jane Eyre plot” – upward mobility; the governess, madwoman, or orphan; colonial careers; the marriage plot – this course is organized so you have the opportunity to do what students are rarely asked to do, but what literary scholars routinely engage in: reading a text multiple times in light of new knowledge and ideas. We will begin by studying Brontë's Jane Eyre as a text that initiated a discussion about women's disempowerment and status. Locating this novel in its complex historical moment – rapid industrial changes, revolutionary ideas, working-class demands, the abolition of the slave trade & slave uprisings in the British colonies, new ideas of race, and an expanding empire – we will study the relation of Jane Eyre's nascent feminism to other radical movements of its day and consider its appropriation as well as displacement of these movements. Alongside the novel and this historical context, we will also consider contemporary feminist critical responses to Jane Eyre. In the second part of the course, we will read a variety of “rewritings” of Jane Eyre – from the 19th c as well as the 20th; from Britain, the US, and elsewhere; from colonial and postcolonial perspectives; from print and visual media – each of which highlights something the original suppressed or neglected. In sum, we will examine both Jane Eyre's continuing popularity as a trope for women's lives and rebellion, as well as the various ways the novel and myth have been critiqued and transformed. In addition to Jane Eyre, our texts will be selected from the following list of books and films: M. E. Braddon’s Lady Audley's Secret, George Gissing’s The Odd Women, A.C. Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories, Henry James’ The Turn of the Screw, May Sinclair’s The Three Sisters, Daphne duMaurier’s Rebecca, E. M. Forster’s A Passage to India, Jean Rhys’ Wide Sargasso Sea, Jamaica Kincaid’s Lucy, Jeanette Winterson’s Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit, Balasubramanyam’s In Beautiful Disguises, Yvonne Vera’s Butterfly Burning, My Fair Lady, Pretty Woman, I Walked With a Zombie. Requirements: two creative papers – one cleaving to Brontë’s novel, the other an “afterlife” story; weekly Moodle postings, two short (7 pages) analytic papers. English 365: Gender and Sexualities: Desire and the Queering of Domestic Fiction Laura Krughoff The novel has long been theorized as a peculiarly domestic literary form. It is, among other things, the genre of home and hearth, of family, of courtship, romance, and matrimony. Simultaneously, domestic fiction has been figured as a sphere not separate from but constituent of political economy. The novel contains, reflects, and perhaps manages, between its covers, the social and political anxieties and desires at play in its age. If this is the case, what happens when the domestic sphere of fiction is queered? We will consider who or what the queer self seems to be and the blurry boundary between fact and fiction in Audrey Lorde’s Zami: A New Spelling of My Name, investigate the status, both personal and political, of queer relationships in Christopher Isherwood’s A Single Man and Larry Kramer’s Faggots, and consider what happens to the category of queer when gender disappears in Jeanette Winterson’s Written on the Body. Our goal will be to understand each novel not just as a work of art but as an act of representation that illuminates what kinds of queer lives are imaginable, contrasting James Baldwin’s Giovanni’s Room with LaShonda Katrice Barnett’s just released Jam on the Vine and Gertrude Stein’s The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas with Monique Truong’s reimagining of these characters in The Book of Salt. We will ask not just what the form of fiction can tell us about queer lives but also what queer characters, relationships, lives and desire do to the form of the novel. English 371: History of the English Language John Wesley The course examines the development of the English language from its roots in Indo-European to the present day. It aims to give students the knowledge needed to approach pre-modern texts with confidence, to develop sensitivity to the ways language functions and changes, and to explore the current state of the language. Students will learn the rudiments of Old English and Middle English, and sample literary texts from those periods. We will study the sounds, structure and vocabulary of English, and give particular emphasis to the way language change reflects and participates in cultural change. Please note: This course is unlike other English courses, and in fact more closely resembles courses in history, foreign language, anthropology, and linguistics. Students should expect to be evaluated by their participation, closed-book test performances, and a final research paper. English 373: Writing and Culture Mita Mahato In this course, we will attempt to understand the enigmatic and shifting term “culture” and what it means to experience or apprehend culture by examining how a variety of writers, artists, and theorists express themselves when producing or confronted by a series of different cultural artifacts and tools/media for expression. Although our examination of culture will allow us to appreciate a number of distinct texts, we will also become sensitive to the complex and nuanced overlap between literature, journalism, critical theory, illustration, photography, and film (to name a few cultural mediators). In approaching culture through these different mediators and media, our main objective will be to explore the pitfalls and benefits of integrating these diverse rhetorics of culture into our own writing. Because this course requires us to experience culture in a hands-on way, you will be required to attend class-related activities, including museum visits and film viewings, on your own time. English 381: Major Authors: Ernest Hemingway Ann Putnam On July 21, 1899, Ernest Miller Hemingway was born in Oak Park, Illinois. One hundred years later, at the Centennial Celebration at the Kennedy Library in Boston, he was compared to Tolstoy and Shakespeare on the one hand—and one of a number of “great, second-rate” writers on the other. Though easily acknowledged as a writer who changed the course of American Literature, there is probably no writer in modern American history who has been more misinterpreted, hated and loved than Ernest Hemingway. Hemingway is a writer who elicits strong feelings from just about everyone. Everybody knows who “Papa” is—or thinks they do. What we hope to discover this semester is the only Hemingway that truly matters, and that is the Hemingway we discover on the page. To that end, we will read many of his greatest short stories, the expatriate novel, The Sun Also Rises, A Farewell to Arms, The Old Man and Sea, and two posthumous works, A Moveable Feast and The Garden of Eden. The class will use a seminar/discussion format, will include two short papers, one longer paper, and one review of a critical study or biography, along with a reading log you’ll keep all semester. There will be no formal exams. You will also have the opportunity to be a discussion leader, panel member, and participate in a group presentation of either Green Hills of Africa, For Whom the Bell Tolls, Death in the Afternoon, or Islands in the Stream. English 431: American Frontiers Tiffany MacBain This course examines literature primarily from the 19th century (and also earlier) to trace the development of national ideologies and mythologies indebted to experiences and imaginings of the North American frontier. Rather than limit ourselves to popular representations of a mid19th-c space west of the Mississippi, we cross temporal, spatial, and cultural borders to achieve a fuller understanding of the literary frontier. We consider the ways in which texts that articulate a variety of experiences connect with and complicate each other. Primary texts include pre-contact oral narratives, western exploration narratives, captivity narratives, pioneer narratives, and frontier fiction. In the second half of the semester students pursue an independent research project to produce a substantive piece of scholarship about frontier literature. To accomplish this goal, students interrogate their interest in a topic to produce a specific research question and a sense of its significance. They then create a research agenda and locate and evaluate primary and critical sources to craft an original argument. The second half of ENGL431 adopts the format of a writing workshop and so relies heavily upon peer-review, critically constructive feedback, and ongoing revision. English 443: Senior Experience Seminar on Rhetoric and Literacy: Authorship Julie Christoph To repeat Foucault's famous question, "What is an author?" The seemingly simple definition of authorship (the fact of having written a text) gets increasingly complicated on closer inspection. Is every writer an author, or are only the "good" ones authors? Where do the boundaries of authorship start and end? Are ghostwriters authors? Are plagiarists authors? If readers play a role in the creation of a text's meaning, then are readers authors? If authorship is important, then how are we to read anonymous texts? Understanding contemporary authorship necessitates exploration into scholarship in literature, rhetoric, law, and philosophy. Together as a class, we will build a shared knowledge base by reading some of the foundational and emerging theories of authorship from these fields, and we will consider these theories in light of literary as well as workaday writing, paying attention to how changing laws and social practices shift the meaning of authorship—and the value of individual texts. As the semester progresses, students will seek to apply and explore questions from the critical scholarship, choosing primary texts that are relevant to their own individual research projects. Humanities 290: Introduction to Cinema Studies Mita Mahato In this course, students develop the skills necessary to communicate intelligently about the artistic medium of film. Students consider key terminology related to visuals, editing, and sound; apply those concepts to a wide variety of examples from the advent of film to the present; consider critical approaches to the medium; and, potentially, produce creative projects that build on formal and critical concepts. In the past, films screened have included Touch of Evil, Vertigo, Mulholland Drive, and Julien Donkey Boy. In addition to regular class sessions, film screenings are required. This course satisfies the Fine Arts approaches core requirement. Humanities 367: Word and Image Denise Despres If we look at images in manuscripts carefully, we will see that they did not represent the word or illustrate it but functioned textually themselves, inviting a complementary process of reading and remembering. This complexity continued to characterize the medieval reading process long after stationers shops (professional manuscript makers for the public) in urban areas displaced the monastic scriptoria, meeting the increasing demand for manuscripts to be used by the literate laity (nonclergy), who could commission compilations of devotional and poetic works with pictures, if the patron was sufficiently wealthy. Contemporary readers of medieval poetry immediately notice the effects of this medieval privileging of seeing as reading, and reading as an illuminative process. Literary works are necessarily economical; images, in patterns through repetition or in complex association as in allegory, convey meaning. Often the images that are most prominent, however, are rooted simultaneously in the religious and material culture the narrative explores; we have to reconstruct these contexts to read beyond the poem’s literal surface to interpretation. Our “print culture” habits work against the “virtual” dreamlike nature of medieval composition, in which “words” were to be heard aloud and “images” visualized, accessing the moral faculty of memory. Often, images take precedence in making meaning on the folio page, dominating words. So, we have to immerse ourselves in the material books of manuscript culture and their images; avail ourselves of scholarship that helps us forge meaning; and imagine our way back to a slower, more visual and aural reading process. To do this, we’ll use facsimiles, digital manuscripts, Image repositories like ArtStor, and the Internet!