Document 12222819

advertisement

:"';:!~.

FIGu"RE

1

2;

SHORT-TEFM M"D 101\"(

P,u"NREAl Rr.""TtJ'RNSON

EQUiTIESAROul'-.'DTHE

,\lORLD'

3 2000-02

20

..

1-

c:

10

~..

~U

Or

-,-I

Q

:. .,

...

u:

~u

u

tJ)

~

~u

:':J

os

=

::

..-,

<

8 1990-99

m1900-2~O2

1

-10

1-20

.,-..)

131:

lj...r Fra Spa Jap Swi Ire Den Net UK Wld Can US Saf Swe A\.IS

"TheCOU1\tr}'

n:ln\es li.~cedin :lbbreviatedrorm along the horizonb! a."ds;Ire(from left to right)Belgium.lt:1!y, Germ~ny, Franc~,

Sp:lin.J:lpan, SwitZerland,lrl:land, Denmark, T1\eNetherlands, The United Kingdom, the ~orld(the weighted a"ernge or the

16 indi\iuu,\1 c()\mtrie.~),c...nad:l,The Unit~ St:lte:l, South Africa, S",'eden,and Au.~trnlia,

Soun:t';EoDin1Son,P. Marsh, und M. S~unton, Triumpb oflbe OptimistS:101 Yea,. ofGloballntleStmem Retun1S(.~ewJer.<e)"

Pr'J)cetonL:niversity Press. 2002) and Global.//lt~tnlent Retunu Year/;ook (.~N }'}'ffiO/London BusinessSchool,2003).

risk. Investors demanded ~ larger reward for equity were quite high. The 1990srepresenteda golden age

market risk exposure. Stock plices fell for three for stocks, and golden ages;by,deflllition, recur 0111)'

successive years from 2000-2002. With markets infrequently.

To understand the risk premium-:-wlLich is the

falling, ll1vest,Pfsstarted to project lower rett1ffis for

the future. Yet it is wrong to overreactto recent stock principal objective of this article-v,'e need to exam111arketperfol"lnanCein projecting future r~quired ine periods that'are much longer tl1ana few year$ o!,"

returns, Just because equities had delivered poor. even a decade. Stock markets are volatile, with

returns since 2000 did not mean that there had been significant variation in year-to-yearreturns. In order

a s~bstantial change in the long-ternl expected to make inferences,we need a long time series that

incorporates bad tin1es as well as good. Figure 1

equity premium.

.

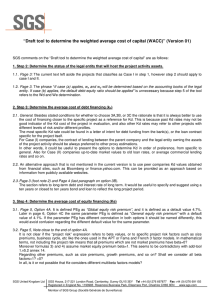

Figure 1 compares U.S. real equity returns to shows real equity returns over the 103-year period

those in 15 otl1er countries and.a world index. 111e 1900-2002 (and which we describe in more detail

figure shows ~nnualized real equity returns over later); these data provide insight into the perspective

2000-2002,and in all 16 countries, equities suffered that longer periods of histO1Yca~ bring. Clearly.

negative returns. In contrast, governnlent securities these 103-year returns are ~uch lower than the.

(not shown in Figure 1) generallyperformed well, so returns during the 1990s, but they also contrast

favorably witl1 the' disappointing returns over 2000that equities markedly underperfolmed both bonds' 2002.

and bills in all 16 countries over2000-2002. Estin1ating the expected lisk premium from tl1eperformance

of equities relative to bills or bonds over this period PRIOR ESTIMATES OF THF. RISK PRFMIUM

",'ould clearly be nonsense. Investors cannot have

To be fair, financial economists generally mearequired or expected a negative return for assuming

:sk. Instead, this was sihlply a very disappointing sure the equity premium over quite long periods.

...riodfor equities. Yet .itwould be equally mislead- Standard practice, however, draws heavily on the

.!g to estimate future risk premiums from data for United States,with most te}.'tbooks citing only t11e

1990-1999. Figure 1 shows that over this. period, U.S. experience. By far the most widely cited U.S.

equity returns (except in Japan and South Africa) source prior to the end of the technology bubble was

\

i

i

1i

.

~

i

~

jI

!

i

}

.~.:~.

",'..=

Stock markets are volatile; with significant variation in year-to-year returns. ..

In order to make inferences, we need a long time series that mc9rporates bad times

as well asgood.

1. See Ibbol.-on Associates, $rod.:s, Bonds, Sills alld hrJIallon Yea/wok

<C'\iQgo: Ihbotson Associates,2000).

2. B3fclays Capit:l!, EqIIity-Gilt Sfl/'f.Y(1999); and Credit SuisseF'u.stBostQn,

"B Eqult)'-Gilf $tltd.V(1999).

lle U.K. evidence turned out to be based on a retrospeCtivelyconstrUCt~d

lose composition. up to 1955, W3Stainted by survivor bias and n3n.,,\V

co. "'~.

29

:

FIGURE 2

ESn.:\U.TEDARIlliMEnc

MEA.! RISK PREl\-mJMS

RElATToJETO BILLS,

~-~~~--

~

&..

!:it:

1998 A1\TD

2001

C,E~

~

.\I..

7.1%

tJ~

-u

\I

co

~August 2001

6

5.5%

~~

--

~ Late1998

_8.5%~

4

8~

,.

",'

05

'C

~

3.4%

2

0

Ibbotson

Key Finance

(1926..;.97)

'Jextbooks

Welch 30-Year Welch 30-Year

Premium

Premium

Welch r-Xear

Premium

publicity. Our own estimateS of a 7.7% mean premium over the longer period from 1900:-2000 was NEW EVIDENCE

1.2Q/olower than the Ibbotson estimate of 8.90/0for

The wide dispersion of estimates,together with

1926-1997. In Avgust 2001, Welch updated his

the dramatic decline in the "expert" consensus

earlie,survey, receiving responses from 510 finance

and economics professors.9 He found that the re- premium between 1998 and 2001, reinforces the

,ondentS to the follow-up questionnaire had re- need to better understand.the historical record. Our

.sed their estimates downward by an average of researchhelps fill the gap by providing" a 103-year

1.6%. They now estimated an equity prelruum averag- history of risk premiums for markets in 16 countries.

ing 5.5% over a 30-yearhorizon, arid 3.4% over a one- The evidence on long-run risk premiums presented

in this article is derived from a unique new database

yearh6rizonCsee Figure 2). Those who had partidpated

in dle earlier survey and those who were taking part comprising annual returns on stocks, bonds, bills,

for the fU"sttln,e estiIriated the same mean pren1iurns. inflation, and currencies for 16 countries over the

..'

Although respondentS to th~ earlier suf\"ey had indi- period 1900-2Q02.The countries include t.l"}eUnited

cated that, on average, a bear market would raise their States and Canada~the United Kingdom, seven

eqtliry premium forecast, Welch repo!1S that "this is in markets from what is now the Euro. currency area,

contrast With the observed fIndings: it appears as if the three other European markets, two Asia-Pacific

recent bear market correlates With lower equity pre- markets, and one African market. Together, these

mium forecastS, not higher equity premitlffi forecasts." countries made up 94% of the free float marlcet

Stili, predi<:llons uf the lc'ng-tt.l!l1 ey :';:~J'1':'-"1." capitalization of all world equities at the beginning

~OO3,and ~"e estimate that they const~tutedover

mium should not be so sensitive to short-term stock ~.~"

90%

by value at the start of our period in 1900}O

m2.rket flucttlations. The changing consensus might

To

compile this database, we assembled the

reflectnew approaches to estimating the premium or

best

quality

indexes and returns data available for

new facts about long-term stock market perforeach

national

market from previous stUdies and

mance, such as evidence that other countries have

other

Sources.lI

Many early equity indexes measur~

typically had historicai premitlms tl'.at were lower

just capital gains. and ignore dividends, thereby

than in the United States.

introducing a serious downward bias. Similarly,

8. E. Di=on, P. Marsh, and M. Stau:1ton.MiiIe7,nfu", Book0: 101 Yea~ t)f

G/oba/ln:.estmel1tReltLrn.t(.a.B~A!.1RO,'1.ondon

Busin~s School, 2001).

9. L Welch, "The Equity Premium ConsensusForeast Re..isited,.\Vorking

~per, Yale School of Management,SepteLnber2001.

10. The Din\SOn-M:lrsh-St:lunton

orson Associates, Chicago, IL

Global R~t\V"I1Sdat:! module is ::va.ilab1efrom

11. Details of our d"t2 SQurceslor a1116C'ountriestogcther wIth full citations

are prov;det! In E. Din.-on, P. M,..~h, ar.d M. S~u!1ton, TrilLmph oftbe Optimist$:

101 l'ea.7 of Global /nLoe.rtme-nl.'1etums

(New Jcrsey: oPrjr,cetonUniversity Press,

2002) a:-.d Global Inuerlment .Relurns Yearbook(ABN ~~\!RO/l.ondon Busines.~

ScllOOl,2003). Wl1=n: possible, we used datafrom pecr-fe\iewed ac.d~mIc papers,

although some StUdieswere previously unpublished. To~:'l the full period from

,-.,-

::;;:.';~.

.' :.

"'.:'

.~,

.,::'. .

Our databaseis more comprehensive and accuratethan pr~ottS x:es~c::l"l;

~4 s.p~

a longer period. We can now set the U.S. risk premium data"alongsiqecomparable

lO3-year risk premiums for 1? other countries; and make international comparisons

that help put the.U.S. experience in perspective.

TABLE!

EQUITY RISKPP,E."'lIUt.1S'

AROUND 1HE WORLD

1900-2002

~-

~:i'"~!:"i';"~~~:;;o.i";~

r!:Auscr~,a;.",;.'1"~'~:'=:;I;.'

"""""'...",.,

"6"'~~~~

--

-'9.1;".~x~'-:;"';"~,.;);~~"!)I~,,,1J

;",""':'-;~'[i';_.,

'~~.~='~-~.'-"'~-"-""~.

~,~~

Belgium

6~ O':';:":-:~;::"~f:;;:?':

,;"£',:w";;,(

"6'::;'.::'~~',o;'~:

~':";!;~'~1'~~'}f"

2.2

--"'-"!o-~-

-~

Ff~:t!"~.':"~~-'!1'*~~~-;:~~':'~~-

~

Denmark

2.2

Germany

3.9

~Italy"

.-f..?'

"".=-=

~

4.3

United

~!v~1'j1.

2..8

~~..,

;!.,

'f!,*.!!fi...~

States

:81

~

3.2

~.

35.5

1 ..

,7,;:;.r~

5.7

16.0

9.0

.-'7.6'

8 ...;2{!:~'~

..;.,.,'",'.;:.

2.7

"""~"4~-"'-

28.8

.~,

30.2

6.4

22.6

~~N="'~~"'-""

3.8

5.9

21.9

"'-~-..4:"""'..;.-~~.'I;\.~;.,.,-_.~",~,.

4.9

21.5

1.9

4.8

-"'..,,-.:= i'!:'~

18.8

.1.4

~- ~ ~;';D1:-"""

7.2

~~~.-.~

.,

~

~;.~~';&.~~

.:=~~

World

~~

5.3

','

5' "!~~'~~~~;.'!-

::J~;:[§:;;F£~~~~i~.t5;J!.:j;J~~~l.!?';.9:'!;;;..£:+1.~t,:;,l~~~;}'

Spain

~

9.4

1.5

.-.w-,'

-~~?~""~-~"'"""""'-""""""""""""""""""""-'

~w.~~'t;.fb~~~'

Switzerland

m!1:~

!~

19.6

"..~,-

20.2

':~9!;3,:!.~t;~~2Q;J).~~~

r1l

"~~-"~~

~~'i"~'

?"";'"

5:4~~~~~~.<}'~ *.:;.~~~

' '="*"...£~';(~~...aJ:.='S"",~~w

= ,=-~3: ; -=...

'...

,i~,~~'

~...",,"=..f

The Netherlands

~~~""~"'-"';;'~~~~~

3.9

.~::::

---iO.3"""32.5~

6.3

~lari'1~-

..:~:'~,:.~.;~,...:..'$~-;",~'-:",:~':i.,~~;"?i,r.,;~,;:

3.8

0":.~':.~'!'

~;,~.}

"""'.-'--."'

4.4

23.1

2.1

16

"'"~

8 .~~}~ O~ ~:~~7

5'-5':;:r..~.Zt:-

i;i&~~~3~.';;;t~~.:.?!~:::;:~.;-,,;:.::5;~~l'..

'1t1"'"'?;;'~

'&~'\.!;"'.~b',J'","\lJ.""~,',,~,J.,,,.,

~"'""-~

-=~

4.4

.'-

19.8

~.

~,..~.~~

.',;

~22

-~...".

5.7

3.8

2.9

~--'to

\l-;,;m,~ 'E~

4.4

20.3'

~~

6.4

17.5

--, ~~"..;,;20.3

;("""a""~

"~i":r&,3;.r;r~:..~,

PlI

,...=~,

16.5

'"

~~;"'~~:iP"(!;~:G

..'~~~"""~;':.'U:!'-"i.'!'

~

3.8

"""_._~:'-~"_r,~

4.9

,

15.0

---~-~~--'The equity risk pr~mium is measur~d here os1 + c:quiry rate of r~tUrndi\ided by 1 + fi.,k.free retUrn, minus 1. Tne stat!!'tics

reported in this table are based on 1033nnual observations for eachcounuy, except Gem~nr which exclud!:S1922-23. when

bill and bondholders experienced retUrnsof -1~

due to h)"perinfl3tion.111erow labcl~d 'Average" is:l simpl~. un~'eight~d

averageof me statistics for d1e 16 indi\idu:ll countries, The row m3rked "\VorJd' is for d1eWorld indcx (~eeteXt).

Source:E. Dimson, P. Marsh, andM. St;tunton, Triulnpb of/be Optimists:101 YeanofGloballnueslme71t Rctun-.s(NewJerse)':

Princeton Univ=ity Press,2002). and GlooollnL'eS1men/Rettirns Yea,"book(ABN W.RO/London BusinessSchool. 200~).

many earlybond indexes record just yields, ignoring GDP.13The left half of Table 1 shows equity premiprjce movements. Unlike most previous long-term ums measuredrelative to the ret1Jrnon Treasurybills

studies of global marketS,however, our investment or the nearest equivalent short-term instrument; the

returns include reinvested gross income as well as right half shows pren1iumscalculated using the same

capital gains. Our databaseis thus more comprehen- equity returns, but relative to the return on 10ng-tem1

sive and accurate than previous researchand spans government bonds. Since the world index is coma longer period.12Furthennore, we Can now set the puted here from the perspective of a U.S. (dollar)

U.S. risk premium data alongside comparable 103- investor, the world equity risk premium relative to

year risk premiums for 15 other countries, and make bills is calculated with reference to the U.S. risk-free

L'1temationalcomparisons that help' put the U.S. (Treasury bill) rate. The world equity premium

relative to bonds is calculated relative to a GpPexperience in perspective.

Table 1 shows the l1istorical equity risk premi- weighted, 16-country,common-currency (here taken

ums for the 16 countries over the 103-year period as u.S. dollars) world bond index.

In each half of the table we show three mea1900-2002.We also display equity premiums ~or01,1f

world equity index; which is a 16-country,common- sures. T'nese are the annualized risk premium, or

currency (here taken as U.S. dollars) equity index geometric mean, over the entil.e 103 yearsj tl1e

with each country weighted by its beginning-of- aritl1ffietic mean of the 103 one-year pren1iul"IlSjand

period market capitalization or (in earlier years) its the standard deviation of the 103one-ye~ premiun1S.

".

, .31

.

'~OtUME 15 NUl-reER 4 .FAtJ

?M~

.J "

FIGUBE3

\'I70RLD\\'1DE-~"'~"UALIZED

EQu1N RISK PP.E1\.{Iu-:.1S

19~2002

;~~I

,

~

.."..

8

e

7

.E

e

~

{

.:f.

\II

~tJ

~

C

\J

.~

u

:~;t.

~\J

',,'1

...

,.:1

','

',;~,

Swi Den Spa Bel. Ire .Fra Net WId UK Can Ita .US Swe Sa! Jap Ger Aus

Getmanye.'tcludes

1922-23.

.

SOurce:Dimson, Iol-arsh,

and S:a.unton.Triumpb oflb;e Optimi$ts:201 Yea~ ofGloball/llIestmel1tReruMU"(pr'.ncetonUni\'~r.i~'

Press."2002)and Global hn~tnl4'll Relllnu YearbOokCA.BNAMRo,tor\don Busir\cssSchool,2003).

While the United States and the United .Kingdom mium. The equity premium for the United Kingdom

have indeed performed well, ~hereis no indication is closer to the worldwide average. While U.S. and

'"'at they are hugely out of line compared .to od1er U.K. equities have perfoffi1ed well, both countlies

r~etS.

are tQward the middle of the distribution of world-'

Over the entire 103-year period, the annual- wide equity premiums.

ized Cgeon1etric)equity risk premium, relative to

Commentators have suggested that survi\~or

bills, was 5.3% for the United States and 4.2% for bias may have led to unrepresentative equity premithe United Kingdom. Averaged across all 16 Ut11S

for the United Statesand the United ~gdom.

countries, the;.risk pren1ium relative to bills was \~i1e legitimate, these concerns are sbme",;hat

4.5%,while the risk premium on the world equity overstated. Ratheri the critical factors are the period

index was 4.4%. Relative to long bonds, the story over which d1e risk premium is estilnated, together

is siInilar. ~he annualized U.S. equity rislc pre., with the quality of the index series. Investors have

mium relative to bonds was 4.4%, and the corre- therefore probably not been greatly misled by a

sponding figure for the United Kingdom was focus on the U.S. and U.K. experiences.

3.8%. Across all 16 countl"ies, the risk premium

The 103-yearhistorical estimates of equity prerelati\'e to bonds averaged 3.8%,and for the world n1iumsreported here are lower than was previously

index it was also 3.8%..14

tl10ught and other studies suggest.Nonetheless, the

.111e annualized equity risk premiums are plot- historical record may' still overstate 'expectations.

ted in Figure 3, In this figure~countries are ranked First, even if we have been successful in avoiding

by the equity premium relative to bonds, displayed survivor bias within each index, we still focus on

as bars. The line-plot presentSeach country's risk markets that survived, omitting countries s\.\ch as

premium relative to bills. It can be seen that .t11e Poland, Russia,or.China.whose compound rate of

United States does indeed have a .historical risk return was -100%. Alth9ugh tl1ese markets ~;ere

premium above the world avel-age,but it is by no relatively small in 1900,15their on1ission probably

means t.'fle countly with the largest recorded pre- leads 'to an overestimate of the worldwide risk~

14. Table 1 s1'()~'sthat the :1nnuallzed~'Orld equit}' risk premium relative 10

" ~':lS-1,4%,comp:lred with 5.3% for the United Sutes. Part of this difference,

"ever,r--fleas tl1e strcngth of me dollar over the period 1900-2002.The ".orld

preniium is romputed here from tl,e ~'orld equity Ind~x expr=ed in dolbrs,

.., order to reflect tl1e perspeCti'"e or a U,S,-based global invesror. Since u1e

currencies of moSt other count.-i~sdeprec'.ateda~

the dollar ovo:r U1e20th

.-

century, u\is lo""ers our esw\l:lte of lhe ~'orld equit)' risk premium re!:\th-e to the

(~'eishled) av=ge of the l~-currtncy-ba.scd esUm31esfor indi..idu~l counrrl.:s.

15. SeeR. Rajanand 1. 7.\n~les. "The Cre3tP.t\'er~: The P01itia offin3nc:i,,1

De\'elopm"'1~ in the 20111CentUry," WorId.'lg ~pcr No. 8178. (C:lmbridgc }.LA.:

N3tional Burc~u of Econon"licRes~rr:h, 2001). lnd our book. cited e3r1ier.

32

,'\

premium.16Second, our pren1iums are measured

Iclati\'e to bills and bonds, which in a number of

rountries )ielded markedly negati,..e real returns.

'":e these "risk-free~ returns likely fell below

;tor expectations, the corresponding equity

pLl:miumsare probably overstated.17

Although there is certainly room for debate,we

(to not consider market survivorship to be the most

important SO1.1rCe

of bias when inferring expected

premiums frorl) the historical record. There are

cogent reasons-for sugge~ting that irivestors expecteda low~r premium than they actUallyreceived:

However, tl'!1shas more to do with a failure to fully

~l1ticipate:

improvemeI)ts in businessand investment

conditions during the second half of the last century,

~n iSS1.1e

that \\-e will ret\.lm to later.

v ARJAnON IN RISK PREMIUMS OVER TIl\ffi

The historical

equity premiums

", 3 are the annualized

or geometric

.", separate one-year

:~~.The b"!,rs m Figure

premiums

that vary a great deai.

4 show the year-by-year

premi-

:: ;'tln1S on U,S. equities

~~':'~'~':as,

:-45% L111931,

~~~

shown in Figure

n~eans of 103

relative

when

to bills}8

equities

earned

The

lowest

-44%

and

~~~:~,~i6. We S3)'omitting noi\;sul"i'ing markets .prob:lbly' gives rise toc"eres"

~--':"I!.:~~~ rl.~kprer:liul\1$bec:luse of Ih~ possibUil}. 1l1.'1t

some de£:lulting c:ountries

;.~~rns of "l~ on bonds, ,,'bile o:quftiesret:lin someresidual..~lue, For such

~"\es"~e ~ post equil}" premium would be positive,

.

?~~e aS~:I sa}. low risk"r~~r:ltes .prob:lbl}'- gjv~ rise to cvetSUto:drisk

..-'

Treasury bills 1.1%; the highest was 57% in 1933,

~'hen eq~ities earned 57.6%and bills 0.30;'0.

Over the

103-year period spanned by Figure 4, the mean

annual excess return was 7.2%, while the standard

deviation was 19.8% (see Table 1). On average,

therefore, U.S. investors received a positive, and

quite large, reward for expoSlue to equity market

risk.

Because the range of excess returns encountered on a year-to-yearbasisis very broad, however,

it can be misleading to label them "risk premiums."

As already noted, investors cannot have expected,

let alone required,. a negative risk prenlium from

investing in equities, otherwise they would simply

have avoided them. All of the negative and many of

the velY low: premiums plotted in Figul:e Ii mtlst

therefore refleCt: unpleasant sl1rprise~. Nor could

investors have required premiums as high as the 570;/0

achieved in 1933. Suchnumbers are iri1plausible as

a reql1ired re"l;\'ardfor risk, and the pJgh realizations

must therefore. reflect pleasant surprises.As a restut,

many writers choose not to refer to historical excess

returns as "risk pren1iums."To avoid confusion, we

refer to the expected or "prospective" risk prelmllffi

when we are looking to the future. When we

J8. Our U.S. equity ro:turns6[2 :\re descn"b.:din E. DL.","on,P. ~!:lr:;h, and ~I.

Stallman, Trillnlpb oftbe OptilnistS:201 YearsofG!oballnl,£'".tmenr Retu11u(Ne""

Jersey: Princcl0n University Pre$S,2002). From J9OC-192;. we use the tquit)'

rerurns tepoctcd in]. Wilson and c.]o:\cs. .An .'.ru1I}'Sis

ofth~ s..~ ;00 tnde.,,3nd

Co"';es's E.~ensions: P,;ce lnde.oces

a..,d St~k RetUrns, 1870-1999; /o/llTlnl of

S'I$/1=S,VoL 75 (2002). pp.505-533; flOln 19215-1970,we llSe the CP-SPOplt3\i2at;otl-"'-eighredindex; and frotl11971 onward, ""t employ tho:\Vilshire;()OOu1dcx.

FIGURES

}.:;)jUSTME!\'TS TO

HISTORICAL AR1TH.l\1EnC

ME.A..~

EQtlITY R1SK

PREMfi.,T?l1S

RELATI'v"E TO

BILLS, 1900-2002

~

\

!

Sorlrr:e:E. Dimson, P. Marsh,andM. Staunton..Triumph aJlhe OpNmisrs:101 Yea/os

aJGlabell1IIt'estmentReturns (NewJerse:

Princeton University PreSs,2002) and Globallnllestmellt ReJlLrnsYearbook(AnN AMRO! London Business School. 2003).

measurethe excessreturn overa period in the past,we racy .It equals approximately orie-tentll of th.eannual

generallyrefer to it as the "historical" risk premium. standard deviation of returns reported in Table 1.

Because one-year excess returns are so vari- The standard error for the United Statesis 1.90/0,

and

able, we need to examine longer periods in the hope tl1erange runs from 1.7%(Australia and Canada)to

that good and bad luck might cancel out. A common 3.5% (Germany). This means that while th~ U.S.

:hoice of time frame is a decade. Figure 4 therefore aritlunetic mean premium (relative to biJ,ls)hasa best

also shows Llle U.S. equity risk premium measured estin1ateof7 :2%(from Table 1), we can be only tWoover a sequence of rolling ten-year periods, super~ thirds confident that the true mean lies within one

Lrnposedon .theannual returns since 1900.This line- standard error of this estln1ate,nainely within tl1e

plot shows that there is clearly less volatility in the range 7.2% j; 1.9%,or 5.3%to 9.1%. Similarly, there

is a 19-out-of-20 probability that the true mean lies

ten-year m~9-.$ures.

Evenover ten-year periods, however, historical within tWo standard errors-that is, 7.2% j; 3:8%, or

e>:cessreturns were sometimes negative, most re- 3.4% to 11.00/0.

cently in tl1e 1970s and early 1980s. Figure 4 also

revealsseveral casesof double-digit ten-year premi- FROM THE PAST TO THE FUfURE

ums. Clearly, a decade is still too short a period for

good and bad luck to cancel out, or for drawing

To estimate the equity risk premiuffi; to use in

inferencesabout investor expectations.Indeed, even discounting future cashflows, we need the expected

with a full centu.ryof data, market flUCtl1ationshave future risk prelniuffi, which is the arithmetic 111ean

an U11pact.

Taking the United Kingdom as an illustl"a- of the possible premiums that may occur. Suppose

lion, we find tl1atthe arithmetic mean annual excess futl\re returns are drawn from .the same distribution

return for the flfSt half of the 20th century was only as those that occuLTedin the past. In this case,the

3.1%,compared to 8.6% from 1950 to dat~. As over expected risk premium is the aritl1ffietic mean (or

a single year, all we are reporting is the excessreturn simple average)of the one-yearhist,orical.premiums.

In Figure 5; the gray bars show the historical

that was realized over a period in the past.

arithmetic mean premium relative to bills for each

country. The U.S. equity pren1ium is 7.2%, ",.hile

Im.precise Estimates

the world equity risk premium is 5.7%. Tl"le

We have seen that very long series of stock .arithmetic mean premiums are noticeably higher

market data are needed for estimating risk pren1i- than the geometric mean premiums (sho\\'n by

\ms. But even with 103.yearsof data, the potential the colored bars) because whenever there is

.naccuracy in historical risk premiums 1s still fairly any variability in annual premiums, the 2rithhigh. Trle standard er:roris a measure of tl1isinaccu- me tic mean will exceed the geometric mean (or

""~,.,., ~~.-- 34.-.

~...

;t:.

i""

The 103-year h1storical estimates of equity premiums ;eported here are lower than

was previously thought and other studies suggeSt. Nonetheless, the historical record

may still overs.tate expectations.

~::

annualiz.ed) risk premium,19 The .diff~rence is countries, such as japan, Italy, France, and espelargest (~nboth absolute terms an? relative to the ciall)' Getrr..2.n)',2.r~ quite l?rge,

;

geometrIc mean) for the countnes that experienced the greatest volatility of returns over the Last

lllSTORY

century (see Table 1).

When returns are lognormally distributed, the

But since history may have tL'lrned O\.1tto be

arithmetic mean return will exceed the geometric unexpectedly kind to (or harsh on) stock market

mean retttm 'by half the variance. The historical investors, there are cogent arguments for going

arithme:ticmeans.plotted in Figure 5 are obviously beyond raw historical estimates.First,the whole idea

affect~dby the historical variances.The latt,er,how- of using the achieved risk premil\m to forecast the

e\'er, can be poor predictors of future volatility. This future req\.1iredrisk pren1iumdepends on having a

.

~'ill be 'especially true for countries witll very high long enough period to iron out good and bad ll\cklevels oNlistorical volatility, where some sources of yet as we noted earlier, our estimatesare imprecise

extreme volatility (such asthose arisirig from hyper- even with 103 years of data. Second, the expected

inflation and tile world wars) are unl~ely to recur. equity risk premium could for good reasol1Svary

We therefore need estinlatesof'expected future risk over time. Third, we must take account .of the fact

premiumsthat are conditional on current predictions that stock market outcomes are influenced by many

factors, some of which (like removal of trade and

of market volatility.

In looking to the future. let us assume for the investment barriers) may be nonrecurring, which

moment that investors in each country exp'ect tile implies projections for the flltl\re premium that differ

same annualized (geometric mean) risk premium from the past.

A comparison of equity returnsbetween the first

."at they have received in the past. We can then

-;mate the expected fu~\re arithmetic mean pre- and second halves of our 103-yearperiod makes the

m for each country by replacing the historical point. Over the fIrst half of the 20th centttry, tile

al!ference between the geometric and arithmetic arithrI:1eticaverage annual real return on the world

means with a qifference based on a contemporary, equity index was 5.1%, whereas over tile period

1950-2002 it was 8.4%. Fo\.'lrteenof the 16 colmtries

rather than the historical, risk estimate.

Historic~lly...theU.S.andU.K, marketsboth had had lower mean premiums in the flIst half-century ,20

volatility level~)6f 200/0.If we take this figure as our with Australia and SouthAfrica being the only excep- .

contemporary risk estimate. and assume that all tions. The 16-country(unweighted) mean annual real

countries with historic~ volatilities in excess of this returnon equitiesin the firsthalf of the 20thcenturywas.. .

over the next 53 years.

will have a future volatility of 20%, we can then 5.1%,versus 9.0:>/0

The larger equity returns earned dllring the

estimate the expected future. arithmetic mean premlUI:llfor each country. The resulting esrunatesare second hali of th~ 20thcentur)" are attribl1table to at.

shown by the line-plot in Figure 5,Note that we have least fOllr factors. First, there was rapid technological

left the historical estimatesunchanged for countries change, unprecedented growtl1 in productivity and

efficiency, and enhancements to the q\.lality. of

with historical volatilities of 20% or below.

For those wishing to forecast future arith- managementand corporate governance.As Europe,

metic mean risk premiums by extrapolating from " North Anlerica, and the.Asia-Pacuicregion emerged

the long-run historical annualized premiunlS, the froln the turmoil of World \Var II, expectations for

adjusted premiums shown by the line-plot in improvement were limited to whit colud be imagFigure 5 are superior to the raw historical arith- ined. Reality alnlost certainly exceeded in,restor

metic means. Using historical volatility estimates. expectations. Corporate cashflows grew faster than

trte figures for the United States and the world investors anticipated, and this higher grov.rthis now

if1.d~.xremain unchanged at 7.2% and 5.7%, re- known to the market and reflected in higher stock

spe'ctively. However, Figure 5 shows that the prices. Second, transaction and monitoring costSfell

rlo~'nward adjustments needed for several other,~ over the course of the century, and this underpinned

19. For e=ple,

the aritlunetlc me"n of rwo eqU:1U1Iikel~' reNnu 01 +25%

and-2(7!111s (+25 -20)/2 -2~o

whiJc t!leir geomettic mean Is zero since (I + 25/

REVISmNG

100) x (1 -201100) -1

-o.

20. Becauseye.r-tOo)'e2r StOCk

retUrr.s :1'1:very vu\atilr: (jee Table 1), tl1ese

differences are Statlstlcally signifior.t at the 95% Il:Vel fCJconly three of these 14

countries. In eCOnOm1Clerms,howl:\"cr, the differences ..-e clearly I~Tge.

35

.:~;f.,}

~.

.

,,":

:i~~"

F.XPECTED

IUSK PREftllUMS

rating of stock prices.

To convert a pure historical estin1ateof .theris~

.ren1ium into a fOl"""ard-looki11gprojection, we

wotud like to reverse~engineeithe factors that drove 1

up stock markets over tl1e last103years. In principle, 1

we need to identify the influence of factors such as ,

.those described. above-:-cash flow ll11provements,

cost reductip.ns,interest rate shocks. and improved

diversification opportunities. To illustrate the latter,

consider d-le dramatic change since 1900 in the

.valuation basis for equity markets. The price/dividend ratio (die reciprocal of the dividend, yield) at

tl1e startof 1900 '¥'v.as

23 in both the United Statesand

tl1eUhited Kingdom; but by the start of 2002, the U.S.

ratio had risen to 64 and the U.K. ratio to 32.

Undoubtedly. this change is in part a reflection of

expected future growtli in earnings and thus real

dividends, so we could in principle decompose

tile impact of this valt13tion change into two

elements: one that reflects changes in required

..

~

~

1:

j

.

:,~

., .;

1;-".

"'.~~1

:2.h

When making future projections, there is a strong case. particularly given the

increasingly integrated nature of inte~ationa1-eapiW

markets, for taking .aglobal

rather than a coun~-by-country

approach to determinirlg the prospective

,

equity risk premium.

.-

basedprojections reviewed earlier, whichever coun- CONCLUSION

tr)" one focuses on.

Fullher adjustmentSshould almost certainly be

The equity risk premium is the difference

madeto historical risk premiums to reflect long-term between the return on risk'"Y

stocksand the return on

cl1angesin capital market condii.io~. Since, in most safe bonds or billsj it is central to corporate finance

colmtri~S,corporate cash flo"Vv"s

historically exceeded and investment. and it is often described as the most

investorexpectations,a further downward adjustment L."1lponant

number in fmance. Yet it is not clear how

to t11eequity lisk premium is in order. A plausible, big the equity premium has bee~ in the past or how

for\vard-looking risk premium for the world's major large it is today.

m,\rketswould probably be on the order of 3% on a

This article presents new e\idence on th~

geometricmean basis. while the correspondirlgarith- histolical risk prenlium for 16 countries over 103

metic rtiean risk premium would be around 5%}6

years. Ollr estinlates are lower than frequently

A Iiteral interpretation of country-by-country quoted historical averages such as the Ibbotson

llistorical averages might suggest that France has a Associates Yearbook figures for the United States,

higher eq\.\ity risk premium,. while Denmark's is and the earlier Barclays Capitaland CSFBstl\dies for

lower. But while there are cellainly differences in the United Kingdom.27The differences arise from

risk betWeenmarkets, they are tmlikely to account bias in previous index construction for the United

for cross-sectional differences in historical premi- Kingdom and, for both countries; from Ot\rt\se of a

ums. Indeed, much of the cross-COt\ntryvariation in longer tinle frame (1900-2002)that incorporates the

historicaleqtury premiuln5 is at~butable to country- earlier pan of tlle 20th centuryaswell as the opening

.c;pecifichistorical eventS that are un1ike~yto recur. years of the new millennium.. Our global foC\.\salso

\Y/henmaking future projections, there is a strong results in rather lower risk pl"emit\ffiSthan hitherto

-;e, particularly given the increasingly integrated assumed. Prior \1ews have been heavily influenced

.lre of international capital markets, for taking a by the experience of the United States,yet we fmd

global ratherthana counuy-by-country approach to that the U.S. risk pren"lil1mis somewhat higher than

the average for the other 15 countries.

determining the prospective eqLuty risk premium.

The historical eqluty premium is often preHowever, just as there must be some true

differencesacross cotmtries in their riskiness, tl1ere sented as an annualized geometric n"lean rate of

past performance in one

mt\st also be vjriation over time in levels of stock return. which S\.lmn"larizes

market risk. .ft: is well known that stock market number. Looking ahead, for capital bt\dgeting pur-:

.volatilit"f"Vv"andersover time, and it is likely. that:thE poses, what is required is tlle arithmetic n"leanof the:)

distribt\tion of possible equity premiulils. The arith"price" of risk-namely the risk pren1ium-alsc

fluctUatesover time. In the days following Septem-" metic mean of past eqtlity prel"lliums may exceedthe

ber 11, 2001. for example, flfiancial market risk wa:5 ge911"letric.mean 'premillffi by several percentage

high, and tl1e equity premium demanded by inves-pointS due to market volatility. In forecasting .the~

tors was probably also high. This depressed !;hI future arithmetic mean premit\m, then, investors or

market. If the terror had escalated,the market ma~y corporate managerswho believethe)Tcan expectthe

have collapsedj but Armageddon did not arrive anc:i same anntlalized risk premium that they ha\'e obthe marketrecovered. Clearly, risk preli1iun1sat:such served in the past still need to adjust for differences

times are above .average.However, it is difficult t0 in volatility. And, for many countries, the volatility

infer changes in expected premiums from allLY that we nlight anticipate today is probably \'eryte

analysisof. historical excessret\.\rns. For corpora1 different from historical market volatility.>e

More fundamentally, however, we have arguedto

capital budgeting purposes, it may be better to ur

tllat pastreturns ha\'e been advantaged by a re-ratLT'lg

a "normal" equity premium most of the time, and'

d~~late from this prediction only when there are due to a general decline in the risk faced by investors

compelling economic reasons to suppose that ex- as the scope for diversification has incre~.sed.We

have illtlstrated one approach that can be used to

pected premiums are unusually high or low.~

RetUrnS:pa11Icipau!lgII1 the RenI Eco!lomy.. Fhrancial AnalystsJoumal, Vol. 59

26. ror il\wtrau,.e estim:1tcs.see Section 13.7 of cui book.

(2003). pp. 88-98, and the 2003 updates to the reportS cited in fo.xnole 2.

.

..21. Note that these organizations have rcce.rulylo~ered their &ingle-country

estimatesof theeqllit)" risk premium. SeeP..IbbotSonandP. Chen,"tong-Run StOCk

t::.;~.~~~:)"

,7

:;:-:=::=

obtainanestimateof the amountby which the required

A plausible, forward-looking risk premium for

rate of return has fallen. In addition, ""..ehave argue;! the ",'orld's major markets would be on the order of .

that pastreturnshave also beeninflated by the inlpact 3% on a geometric mean basis, while tile.,.correof goOd luck. Since the nliddle of tl1e last century, sponding arithn1eticmean risk pren1ium would be

equity cash flo""rs have ahnost cenaUliy exceeded around 5%. These estinlates are lower tilan the

..e>:pectations.

Stock markets have therefore risen for historical premiUln5 quoted in most textbooks or

reasonsthat are ulilikely to be repeated.l1lis meal1S cited in surveysof finance acaden1ics.Nonetlleless,

thatwhen developing forecastSfor the futlire, investors they represent our best estimate of the equity risk

and managersshould adjUsthistorical risk prenliurns premium for corporate capital budgeting and valudd~ward for the iil"lpact of thesefactors.

ation applica~ons.

"

B ELROY DL"'1S0N

.MIKE

is Profess.orof Finance at London Business School.

is DireCtor of tile London Share Price Database at Londo:1

Business School.

.PAUL

MARSH

is Professorof Fmanceand AssociateDean. Finance Programmes

at London Bl,lsmessSchool.

?l8

STAUNTON