Regional Health Quality Improvement Coalitions Lessons Across the Life Cycle

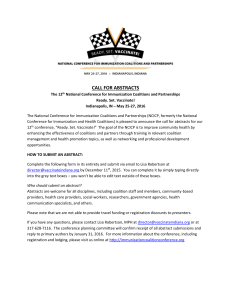

advertisement