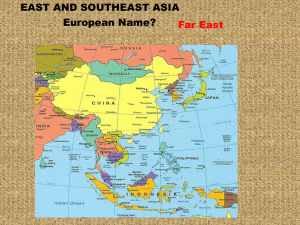

THE CHANGING ASIAN POLITICAL-MILITARY ENVIRONMENT IS ASIA HEADING TOWARD RIVALRY?

advertisement