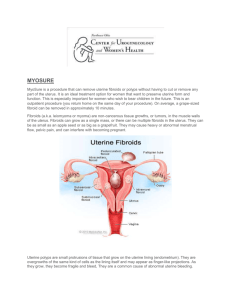

R Uterine Artery Embolization: A Systematic Review of the Literature

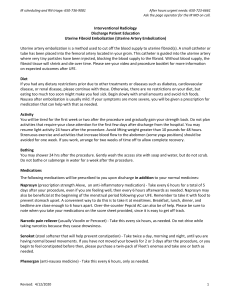

advertisement