Document 12185688

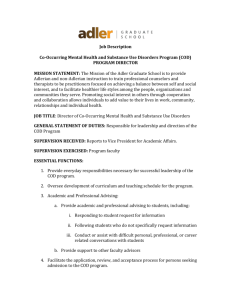

advertisement