Document 12182142

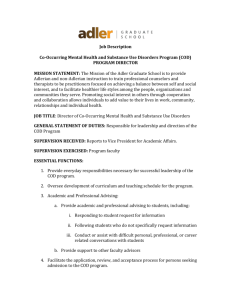

advertisement