Political Advances amid Litigational Defeats: The Indirect Effects of Crimtort Causes 1

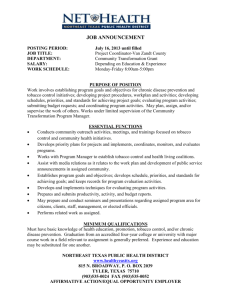

advertisement