INFRASTRUCTURE, SAFETY, AND ENVIRONMENT 6

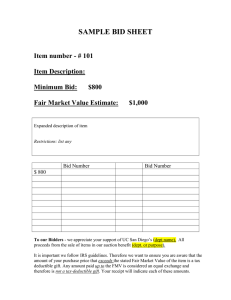

advertisement