Gatekeeper Training for Suicide Prevention A Theoretical Model and Review of the

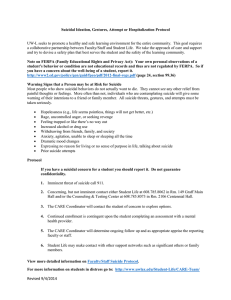

advertisement