P Program Graduates D

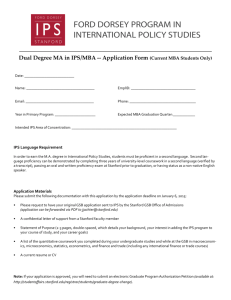

advertisement