Governance Challenges as a Risk for Agricultural Development

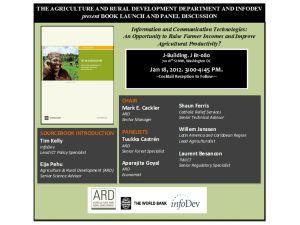

advertisement

Governance Challenges as a Risk for Agricultural Development Regina Birner Chair of Social and Institutional Change in Agricultural Development University of Hohenheim • "Good governance is perhaps the single most important factor in eradicating poverty and promoting development." Kofi Annan addressing the General Assembly of the United Nations in 1998 World Development Report 2008: Agriculture for Development “Governance is essential to realize an agriculture-for-development agenda. In fact, governance problems are a major reason why many recommendations in the 1982 World Development Report on agriculture could not be implemented.” (p. 246) Agriculture is back on the international development agenda! • Events – G8 L’Aquila Statement 2009 – Food price crisis of 2008 L’Aquila Meeting – World Development Report 2008 – Comprehensive Africa Agriculture Development Program (CAADP) – Maputo Declaration of African Heads of State 2003 • After years of neglect - increased commitment of governments and donor agencies to invest in agriculture • Need to overcome the governance challenges of agricultural development – ..to avoid that the world will turn its back on agriculture again! Contents 1. What types of governance challenges are involved in agricultural development? 2. Why do they occur? And why do they constitute a risk? 3. How to assess the governance risks in agricultural programs? – A case study from Uganda 4. Conclusions Governance challenges: Some examples Small reservoirs in Northern Ghana Big hope for a sustainable agricultural development in Africa But how to make them work? Corruption in infrastructure provision! Small reservoirs for irrigation in Northern Ghana Irrigation, by date of construction or rehabilitation of reservoir 60 Irrigate ‐ Catchment/Reservoir 13 50 7 40 Irrigate ‐ Irrigable Area 30 20 10 39 1 3 4 4 14 2 2 3 10 0 Unknown No Irrigation 3 <=1980 15 Problems in construction 6 1981‐1993 1994‐1999 2000‐2006 IFPRI survey 2006/07 Governance challenges: Some examples Participatory irrigation management in India Investment in rehabilitation of canals, to be managed by water user associations Elite capture! … some farmers break the lining to divert water to their fields Governance challenges: Some examples Agricultural extension in Ghana But most farmers, especially female ones, do not have access to extension services 14% 12% 12% 12% 11% 10% Absenteeism! Exclusion! 8% 6% 4% Important service to promote innovation 1.8% 2% 0% 2.1% 1.4% 0.0% Forest Zone Male HH heads 0.0% Transition Zone Female HH heads 0.5% Savannah Zone Female Spouses ISSER-IFPRI Survey 2008 Governance challenges: Some examples Food and Nutrition Programs in India Closed: Child Care Center (Anganwadi) in Bihar Mid-day meals: A promising strategy to improve nutrition Absenteeism! Leakages! What are the reasons behind the governance challenges in agricultural and rural programs? • Market failure (Binswanger & McIntire, 1987) – Transaction costs; risks; information asymmetries; public goods; externalities • Government failure Neglect of agriculture – urban bias (Lipton, 1977) Political capture of agriculture (Bates, 1981) – Nature of agricultural services (Birner & von Braun, 2007) transaction-intensive in terms of space & time require discretion (Woolcock & Pritchett, 2004) Scope for corruption – may be linked to party financing Community failure Collective action problems (Hardin, 1968; Ostrom, 1990) Elite capture; exclusion (Agrawal & Gibson, 1999) Three types of governance challenges 1. Human resource management challenge – Major problem in agencies that employ relatively large numbers of frontline service providers (e.g., agricultural extension agents, veterinary assistants, nutrition advisors) – Problems of supervision and creation of incentives – Resulting in absenteeism and low performance 2. Targeting challenge – Major problem in programs that provide private goods (e.g., food, fertilizer subsidies, cash) – targeted to poor households or household members 3. Leakage and procurement challenge – Major problem in programs that involve contracting between public and private sector (e.g., infrastructure, grain procurement) Risks for different types of programs caused by governance challenges Human resource management challenge Targeting challenge Leakage and procurement challenge Agricultural research Agricultural extension Irrigation and other infrastructure investment Public food grain procurement and buffer stocks Food‐ or cash based safety nets Nutrition‐education programs Major risk Intermediate risk Risks for different types of programs caused by governance challenges Human resource management challenge Targeting challenge Leakage and procurement challenge Agricultural research Agricultural extension Irrigation and other infrastructure investment Public food grain procurement and buffer stocks Food‐ or cash based safety nets Nutrition‐education programs Major risk Intermediate risk Risks for different types of programs caused by governance challenges Human resource management challenge Targeting challenge Leakage and procurement challenge Agricultural research Agricultural extension Irrigation and other infrastructure investment Public food grain procurement and buffer stocks Food‐ or cash based safety nets Nutrition‐education programs Major risk Intermediate risk Risks caused by governance problems - A regional perspective - The World Bank’s Aggregate Control of Corruption Indicator (2010) http://info.worldbank.org/governance/wgi/sc_country.asp The World Bank’s Aggregate Governance Effectiveness Indicator (2010) http://info.worldbank.org/governance/wgi/sc_country.asp Remnants of an agricultural development project in DR Congo The governance-dilemma of agriculture-based countries • “Agriculture-based countries” – have the largest potential to use agriculture as an engine of pro-poor growth, – have the highest risk of governance failures. • Problems – Investments in agriculture have limited effect. • Returns to agricultural investment lower than in sectors that face fewer governance challenges. – Donor fatigue – underinvestment in agriculture • Donors prefer “easier” sectors, e.g., primary education • Agriculture’s potential for pro-poor development remains underutilized. Negative downward spiral. How to assess the governance risks in postconflict projects? A Case Study from post-conflict projects in Uganda Northern Uganda Specific governance challenges in post-conflict situations • Need to ensure food security and help farmers rebuild agricultural livelihoods – Need to provide access to food, seeds, fertilizer, tools, etc. (all private goods) • on a large-scale – need to reach entire population, not just pilot project sites • in a situation where – public sector institutions are weak or absent and – social capital may have been destroyed by the conflict, limiting the prospects of community-based solutions. Implementation Mechanisms used by Different Agricultural Projects • Procurement and distribution of agricultural assets by implementing agency – Government: • Restocking Program under Prime Minister’s Office (district-level procurement); • National Livestock Productivity Improvement Project under the agricultural ministry (national-level procurement) – NGOs: Heifer International (US NGO); GOAL (Irish NGO) • Procurement and distribution of agricultural assets by farmers’ groups/community-based organizations – Funds channeled through public accounts: NAADS – Funds channeled through group’s private accounts: NUSAF • Input voucher programs – Vouchers for work: RALNUC/DAR; without work: Caritas • Cash for work programs: Int’l. Committee of the Red Cross Research Objectives and Approach • Project – Funded by German Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) – Implemented by IFPRI, Oxfam (Marc Cohen) and DIW • Goal – Develop a tool for assessing the governance risks of postconflict projects that aim to help farm families rebuild their agricultural livelihoods • Approach – Comparison of projects that use different implementation mechanisms – Use of a participatory qualitative research tool called “Process Netmap” for risk assessment • Idea: Mapping the implementation process step-by-step to identify “entry points” for governance problems Process Net‐Map Participatory Mapping Method http://netmap.ifpriblog.org/ Phase 1: Ask the respondent how the process started * Mark actors with stickers on paper * Draw arrows between the actors * Number the arrow and note down the process Phase 1: Ask the respondents for the next steps * Continue to add actors and arrows * A process can involve more than two actors Phase 1: Continue until the process is completed (e.g., agricultural assets delivered to group members; accounting completed; vouchers reimbursed) Phase 2: Ask respondent how much influence actors had on the outcome * Use checkers game pieces to visualize influence on a scale from 0-8 * Discuss reasons for influence levels Phase 3: Discuss “problem areas” and possible solutions * Refer to cases that the respondent has heard about (e.g., in other sub-counties/districts) * Critical areas: fund flows; signatures for authorization; procurement decisions National Agricultural Advisory Services (NAADS) Features: - Contracts with service providers - Distribution of agricultural inputs 11 Bids 10 10 District Agricultural Officer Sub-County Chief 17 Forum Chair 12 7 LC3 Chair & Councilors District Internal Auditor 16 SC Farmers’ Forum Secretary of Production Subject Matter Specialist SC NAADS Coordinator 8, 13, 15 Procurement Committee 14 5 Input suppliers SC Sub-Accountant 17 2 9 18 17 1, 5,6 Private service providers Parish Chiefs Farmers’ groups Parish Coordination Committee 5 1. Facilitate group formation 2. Collects and submits farmers’ co-funding 3. Identify and appoint CBF 4. Provide allowance and bicycle 5. Select enterprise 6. Train farmers, establish demo plots 7. Has meeting, decides on bidding 8. Invites bids 9. Send bids 3 Group’s chairman 5 4 Community-based facilitator (CBF) 10. Open and evaluate bids 11. Shortlist 3 bidders 12. Can veto shortlisted bidders, based on experience 13. Negotiates with input suppliers 14. Award contract; issue Local Purchase Order 15. Provides inputs to sub-county office 16. Advises on quality of inputs; can reject 17. Issues check (with signatures / approval) 18. Distributes inputs to farmers District Agricultural Officer 11 Bids 3 10 10 LC3 Chair & Councilors 7 17 SC NAADS Coordinator 7 8 Procurement Committee 7 8, 13, 15 14 5 18 Parish Chiefs 5 Input suppliers Parish Coordination Committee x 5 4 Perceived influence level on outcome (Scale 0-8) 2 9 5 3 Group’s chairman 6 5 3 SC Sub-Accountant 17 17 1, 5,6 Farmers’ groups 2 District Internal Auditor Sub-County Chief 7 Forum Chair 12 3 3 16 SC Farmers’ Forum Secretary of Production Subject Matter Specialist Private service providers 4 4 Community-based facilitator (CBF) 8 11 Bids 10 10 District Agricultural Officer Sub-County Chief 17 Forum Chair 12 7 LC3 Chair & Councilors District Internal Auditor 16 SC Farmers’ Forum Secretary of Production Subject Matter Specialist SC NAADS Coordinator SC Sub-Accountant 8, 13, 15 17 Procurement Committee 14 Input suppliers 5 2 9 18 17 1, 5,6 Private service providers Parish Chiefs Farmers’ groups Parish Coordination Committee Flow of funds Sign on checks / control 5 3 Group’s chairman 5 4 Community-based facilitator (CBF) Entry points for leakages / bribery Entry points for influencing procurement Northern Uganda Social Action Fund (NUSAF) Office of the Prime Minister Regional Office NUMU Chief Administrative Officer CAO NUSAF Accountant NUSAF District Technical Officer (NDTO) District Executive Committee District Technical Officers LC5 Chair & Councilors Community Development Officer LC3 Chair & Councilors Service Providers NUSAF Facilitators Stanbic Bank Input sellers Group leaders Contractor Fund flows in NUSAF Procurement Committee Authorization Group members LC1 Chair & Councilors District Office of the Prime Minister Regional Office NUMU Chief Administrative Officer CAO NUSAF Accountant NUSAF District Technical Officer (NDTO) District Executive Committee District Technical Officers LC5 Chair & Councilors Community Development Officer District LC3 Chair & Councilors Service Providers NUSAF Facilitators Stanbic Bank Input sellers LC1 Chair & Councilors Group leaders Contractor Fund flows in NUSAF Procurement Committee Authorization Group members Entry points for leakages / bribery Challenges and Opportunities in NUSAF • • Opportunities – Placing funds directly into the hands of farmers’ groups • Avoiding sub-standard inputs – Evidence from case study that system can work • Reducing opportunities for leakages at sub-county level Challenges – Group leaders may take advantage of group members • Especially if only group leaders are literature • Funds provided for other purposes than inputs problematic – “Ghost groups” and “ghost projects” – Challenges of accounting (e.g., sellers of oxen just sign in a book) – Efforts to control this problem created new leakage opportunities – Parallel structure to local government may reduce accountability • Even though it also reduces opportunities for leakages Seed Voucher Program Caritas Catholic Relief Services Financial Manager Program coordinator 10 7 2 Centenary Bank 9 9 6 9 5 Extension supervisor Facilitators / Specialists Community Resource Person Escort Accountant 6 Program Manager Seed fair Army commanders 10 Executive Director 1 Archbishop Landlords 8 Stockists Seed suppliers 3 Farmers Groups 4 Volunteers 11 Elected District Leaders Church Government authorities District Agric. Officer 9. Attend meeting at Bank 1. Print vouchers; deliver against receipt 10. Sign checks; keep documents in store 2. Assesses number of vouchers needed and passes them on with receipt book 11. Receive cash or checks; sign receipt 3. Hands out vouchers at seed fair 4. Use vouchers to buy seeds after collective bargaining 5. Collects vouchers; gives receipt 6. Passes on vouchers against receipt 7. Confirms vouchers; enters data; stores them. 8. Bring receipts to meeting held at Bank Catholic Relief Services Financial Manager Program coordinator 10 7 2 Centenary Bank 9 9 9 5 6 Extension supervisor Facilitators / Specialists Community Resource Person Escort Accountant 6 Program Manager Seed fair Army commanders 10 Executive Director 1 Archbishop Landlords 8 Stockists Seed suppliers 3 Farmers Groups 4 Volunteers 11 Church Elected District Leaders Government authorities District Agric. Officer Entry points for leakages / bribery DANIDA programs • • • • Restoration of Agricultural Livelihoods Northern Uganda (RALNUC) Danish Support to Development Assistance to Refugee Hosting Areas – Agricultural Related Activities Component (DAR) Mechanism: Agricultural input vouchers for public works • Advantages: Self-targeting; creation of infrastructure Experience (according to Impact Monitoring Survey 2008) • Substantial positive impact on agricultural productivity and income • Requires awareness creation • Extensive mobilisation coupled with radio campaigns effective in: • Empowering communities to deal with dishonest Project Management Committees • Minimizing household sale of vouchers (7% DAR, 26% RALNUC) • Enhancing participation in public works Other insights • Cash for land preparation • Payment of wage to farmers for preparing their own land (implemented by Int’l. Committee of the Red Cross) • Replaced input voucher program after management was convinced that participants would also use cash for inputs • Advantages • Easier to implement than voucher program • Transparent: easy to inform participants (e.g., by radio) what they are entitled to • Farmers have high incentives to use wage for farm inputs as they have already prepared their land • Problems involved in managing public infrastructure construction avoided, but no infrastructure created Summary Risk Assessment of Governance Challenges Mechanism Selftargeting Procurement by implementing agency Meeting SubCapture farmers’ standard by group preferences material leaders Kickbacks by staff Complexity Procurement by groups, funds channeled through: public accounts (NAADS) groups’ private accounts (NUSAF) Input vouchers with public works (RALNUC) without public works (seed fairs) Cash for work Policy Implications Assess ex-ante which mechanism is most appropriate Capacity of the implementing agency Type of farmers’ needs (need for differentiation/ targeting) Possibility to judge quality of inputs Empower farmers to hold providers accountable Increase transparency (sensitization; radio campaigns) Farmers need to know what they are entitled to! Establish functioning complaint mechanisms Invest in group formation and internal accountability (e.g., social audit meetings) Policy implications Strengthen internal accountability mechanisms in implementing agencies Effective use of incentives and sanctions, especially in public sector agencies Foster professionalism Use opportunities of external evaluation Consider trade-offs in institutional design Autonomous institutions versus strengthening local governments and ministries Conclusions • Governance challenges – pose a major risk to agricultural development; – arise from the characteristics of the agricultural sector; – are especially prevalent in agriculture-based economies; – constitute a particular threat to agricultural programs in post-emergency situations. • Strategies to overcome the governance challenges of agricultural development – need to apply a “best-fit” approach – there is “no free lunch in reforming governance,” – can be informed by risk assessment tools, – need to rely on experimentation and learning. Thank you for your attention! References • Agarwal, A. and C.C. Gibson 1999. Enchantment and Disenchantment: The Role of Community in Natural Resource Conservation. World Development 27:629-49. • Bates,R.H. 1981. Markets and States in Tropical Africa-The Political Basis of Agricultural Policies. Berkeley: University of California Press. • Binswanger,H. and J.McIntire 1987. "Behavioral and Material Determinants of Production Relations in Land-Abundant Tropical Agriculture." Journal of Economic Development and Cultural Change 36(1):73-99. • Birner, R., M. Cohen, and J. Ilukor, 2011. “Rebuilding Agricultural Livelihoods in Post-Conflict Situations: What are the Governance Challenges? The Case of Northern Uganda.” Kampala: USSP Working Paper 07, Uganda Strategy Support Program (USSP), International Food Policy Research Institute. http://www.ifpri.org/sites/default/files/publications/usspwp07.pdf References • Birner, R., A. Quisumbing, and A. Nazneen, 2010. “Crosscutting Issues: Governance and Gender.” Dhaka: Paper Presented at the Bangladesh Food Security Investment Forum, 26–27 May 2010, Dhaka http://bids.org.bd/ifpri/crosscutting2.pdf • Birner, R. and J. von Braun, 2009. Decentralization and Public Service Provision—A Framework for Pro-Poor Institutional Design, in: Ahmad, Ehtisham and Giorgio Brosio (Eds.): Does Decentralization Enhance Poverty Reduction and Service Delivery? Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, UK, pp. 287-315. • Hardin, G., 1968. "The Tragedy of the Commons." Science 162:1243-8. • Kaufmann,D., A.Kraay, and M.Mastruzzi, 2010. “The Worldwide Governance Indicators: Methodology and Analytical Issues.” Washington, DC: World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 5430, World Bank. References • Lipton, M., 1977. Why Poor People Stay Poor: A Study of Urban Bias in World Development. London: Temple Smith. • Ostrom, E., 1990. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. New York: Cambridge University Press. • Pritchett, L. and M. Woolcock 2004, "Solutions When the Solution is the Problem: Arraying the Disarray in Development." World Development 32(2):191-212. • World Bank (2007). Strengthening governance, from local to global. In: World Development Report 2008: Agriculture for Development. World Bank, Washington D.C. pp. 245-265.