Stereotypes of the Homeless: The Target’s Perspective Carolyn Weisz, Psychology

advertisement

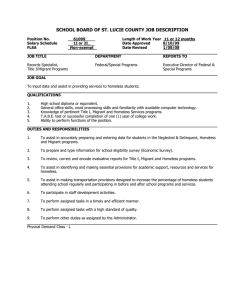

Stereotypes of the Homeless: The Target’s Perspective Carolyn Weisz, Psychology Renée Houston, Communication Studies University of Puget Sound Contact: cweisz@ups.edu. Please do not cite without permission of authors. Student Assistants: Carrie Clark, Karen Czerniak, Sonia Ivancic, Tom Van Heuvelen, Alex Westcoat, Natalie Whitlock, Jenny Yu Supported by The Pierce County Road Home Leadership Team and the Boeing Company Introduction Homeless individuals face potential health and safety risks, and they are also the targets of social stigma. Research suggests that attitudes toward homeless people are extremely negative (e.g., Fiske, Cuddy, Glick, & Xu, 2002; Harris & Fiske, 2006; Phelan, Link, Moore & Stueve, 1997). As part of an interdisciplinary project on homelessness in Pierce County, WA, this research examined homeless people’s own perceptions of their group as well as their beliefs about how their group is perceived by others. Homeless individuals’ beliefs about negative attitudes others hold toward them are important to understand because these beliefs may affect job- and help-seeking behaviors, and other variables related to well-being. We predicted that these beliefs would be quite negative, and, specifically, more negative than homeless individuals’ own beliefs about their group and than perceptions reported by individuals with homes. Introduction Homeless individuals face potential health and safety risks, and they are also the targets of social stigma. Research suggests that attitudes toward homeless people are extremely negative (e.g., Fiske, Cuddy, Glick, & Xu, 2002; Harris & Fiske, 2006; Phelan, Link, Moore & Stueve, 1997). As part of an interdisciplinary project on homelessness in Pierce County, WA, this research examined homeless people’s own perceptions of their group as well as their beliefs about how their group is perceived by others. Homeless individuals’ beliefs about negative attitudes others hold toward them are important to understand because these beliefs may affect job- and helpseeking behaviors, and other variables related to well-being. We predicted that these beliefs would be quite negative, and, specifically, more negative than homeless individuals’ own beliefs about their group and than perceptions reported by individuals with homes. Participants and Methods Homeless Sample • 214 homeless adults (116 men and 98 women) recruited at many locations throughout Pierce County, WA, completed surveys orally or in writing. They received a $20 gift card. • Age: 19-65 years. • Race: 55% White, 21% Black, 8% Native American, 5% Hispanic, 1% Asian, 10% Mixed or Other. • 43% reported having a diagnosed mental illness. 44% reported a drug or alcohol addiction. 30% reported currently using drugs or alcohol on a regular basis. Comparison Sample • 50 business leaders and residents were recruited from three sources: a master mailing list of Pierce County businesses, the Qwest-dex phone book, and a list of citizens who had participated in a survey on attitudes on an Affordable Housing Levy. Participants completed a survey prior to engaging in focus group discussions on homelessness. They received $50. Stereotype Measure • Homeless and non-homeless participants indicated whether they thought five statements representing negative stereotypes about the homeless were true or false. – – – – – Most of the homeless are drug addicts or alcoholics. Most of the homeless do not want to work. The homeless are largely responsible for petty crime. Large homeless populations create fear and danger in communities. Most homeless people don’t want to be helped. • Homeless participants also indicated the answer that they thought nonhomeless individuals would choose most often for each item, and answered a battery of other measures. Table 1. “True” Responses to Statements about Homeless People Item Homeless Believe ( n = 209) Homeless Think Others Believe (n = 209) NonHomeless Responses (n = 50) Most of the homeless are drug addicts or alcoholics. 35.7% 83.1% 38.0% Most of the homeless do not want to work. 23.4% 74.5% 20.0% The homeless are largely responsible for petty crime. 24.4% 75.8% 20.4% Large homeless populations create fear and danger in communities. 56.8% 80.8% 88.0% Most homeless people don’t want to be helped. 12.1% 69.5% 8.0% Mean number of “True” responses out of 5 (SD) 1.55b (1.32) 3.89a (1.70) 1.74b (1.14) Results Our primary analyses compared the sum of true responses for the five items for the homeless participants (alpha = .57), the homeless participants’ beliefs about the outgroup responses (alpha = .88), and the non-homeless participants (alpha = .53). As expected, homeless participants thought outgroup members would endorse significantly more items as true than outgroup members actually endorsed, t(251) = 8.49, p < .001, and than homeless individuals endorsed as true themselves, t(191) = 16.08, p < .05 (See Table 1). The mean number of items actually endorsed by homeless and non-homeless individuals did not differ, t(243) = .94, p = .35. Analyses of individual items were conducted using chi-square and McNemar tests. For the four items that involved negative characteristics of homeless people, the frequency of true responses was higher for homeless individuals’ perceptions of the outgroups’ responses than for their own beliefs, ps < .001, and the actual beliefs reported by the non-homeless, ps < .001. Homeless and non-homeless individuals’ own responses did not differ for these items, ps > .10. For the single item describing beliefs about the effects of homeless individuals on the community (i.e., create fear and danger), homeless individuals’ beliefs about the responses of the non-homeless and the non-homeless’ own responses did not differ, p > .10, and were both higher than homeless individuals own beliefs, p < .001. Exploratory analyses revealed that the responses of the homeless sample did not vary by gender, but that White homeless participants thought the outgroup had more negative impressions of the homeless than did non-White homeless participants, F(1, 175) = 21.62, p < .001. There were no effects of race or gender for homeless individuals’ own responses. Discussion Our findings suggest that homeless individuals believe that they are viewed quite negatively by those who do not share their homeless status. Moreover, they perceive these negative stereotypes as more extreme than the views they hold themselves about homeless individuals as a group. These findings add to the larger literature on stigma which examines perceptions of discrimination from the target’s perspective (e.g., Levin & van Laar, 2006; Major & O’Brien, 2005). We also found that homeless people’s perceptions of negative stereotypes held about them are more negative than the perceptions reported by a sample of non-homeless individuals from the same community. It is difficult to discern whether this difference reflects inaccurate perceptions held by the homeless or reporting biases by the non-homeless. The fact that non-homeless individuals were more willing to endorse a statement about the negative effect of homeless people on the community than statements about negative characteristics of homeless people suggests that some form of social desirability bias or modern prejudice (e.g., Gaertner & Dovidio, 1986) may indeed be present. Regardless of the accuracy of perceptions by homeless people about the negative attitudes others hold about them, these beliefs may have important practical consequences. Our ongoing research will examine links between homeless people’s perceptions of stigma and outcomes related to well-being and behavior. For example, individuals who fear negative judgment or treatment may be less likely to apply for jobs, join community organizations, or seek help or services. References Fiske, S. T., Cuddy, A. J. C., Glick, P., & Xu, J. (2002). A model of (often mixed) stereotype content: Content and warmth respectively follow from perceived status and competition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82, 878-902. Gaertner, S. L., & Dovidio, J. F. (1986). The aversive form of racism. In J. F. Dovidio & S. L. Gaertner (Eds.) Prejudice, discrimination, and racism (pp. 61-89). San Diego: Academic Press. Harris, L. H., & Fiske, S. T. (2006). Dehumanizing the lowest of the low: Neuroimaging responses to extreme out-groups. Psychological Science, 17, 847-853. Levin, S., & van Laar, C. (Eds.) (2006). Stigma and group inequality: Social psychological perspectives. Mahway, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. Major, B., & O’Brien, L. T. (2005). The social psychology of stigma. Annual Review of Psychology, 56, 393-421. Phelan, j. C., Link, B. G., Moore, R. E., & Stueve, A. (1997). The stigma of homelessness: The impact of the label “homeless’ on attitudes toward poor persons. Social Psychology Quarterly, 60, 323-337.