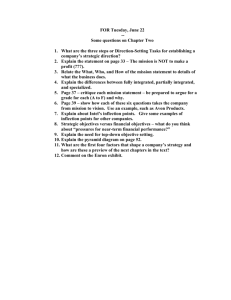

The RAND Frederick S. Pardee Center 6

advertisement