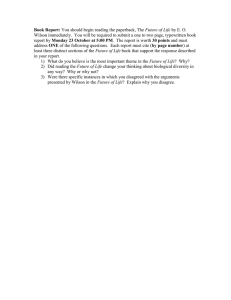

Botanist* Wilson E. H.

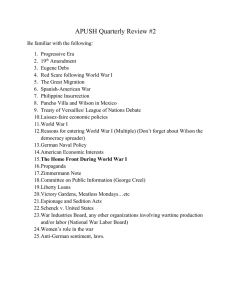

advertisement