Document 12151232

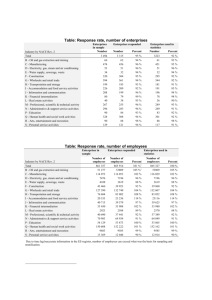

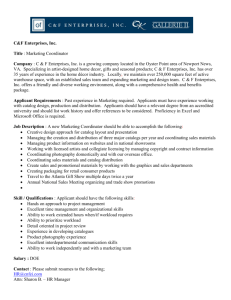

advertisement