Document 12144402

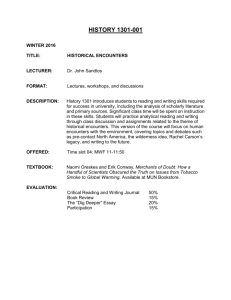

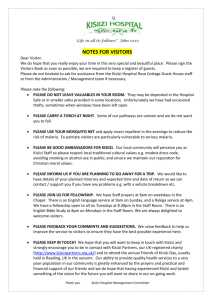

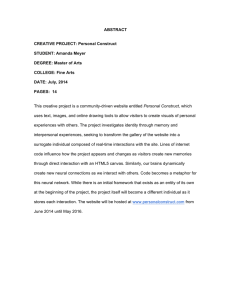

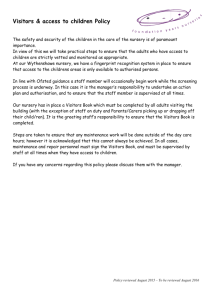

advertisement