Increased creditor rights, institutional investors and corporate myopia Sterling Huang Jeffrey Ng

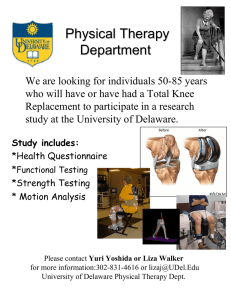

advertisement