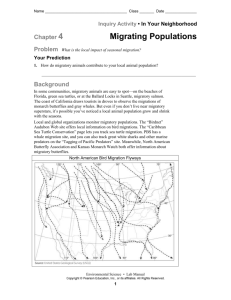

migratory species and climate change impacts of a changing environment

advertisement