ZEF Working Paper Series 90

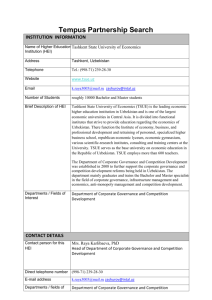

advertisement