ZEF Working Paper Series 95

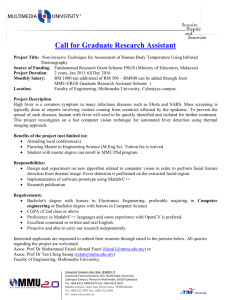

advertisement