ZEF Working Paper 103 Aram Ziai Postcolonial perspectives on ‘development’

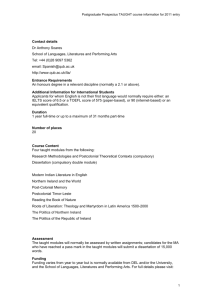

advertisement