ZEF Working Paper

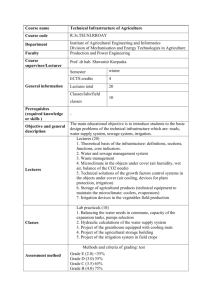

advertisement