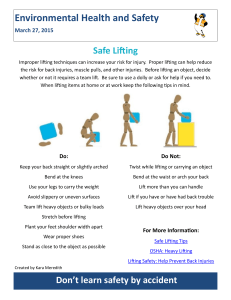

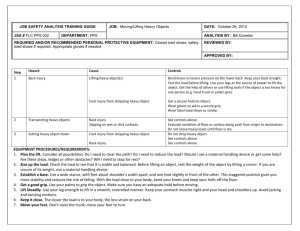

A BACK INJURY

advertisement