Ticks and Tick-borne Diseases: More than just Lyme Important Emerging Pathogens 4/27/2012

advertisement

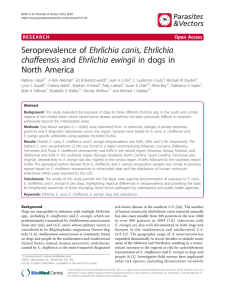

4/27/2012 Ticks and Tick-borne Diseases: More than just Lyme http://www.scalibor-usa.com/tick-identifier/ Katherine Sayler and A. Rick Alleman Important Emerging Pathogens Increase in disease prevalence in pets and people Perceived emergence in pets Positive control Better diagnostic capabilities Anaplasma Ehrlichia Lyme True emergence Increase and spread of tick vectors and wildlife reservoirs Housing developments in rural areas The Importance of the Veterinarian We are aware of and equipped to diagnose vector-borne disease and/or exposure to vector-borne pathogens in pets Educate owners of ppets exposed to vector-borne pathogens Positive control Anaplasma Ehrlichia Lyme Many are zoonotic pathogens Dogs are sentinels for human exposure People and pets have similar environmental exposure 1 4/27/2012 Tick-Borne Pathogens Expert evaders of the host immune system Rapid antigenic variation Nidus of infection in various host tissues Chronic, persistent infections in people and pets Chronic, vague illnesses affecting various organ systems Vector-Borne Diseases are Often Misdiagnosed Many people we have encountered with vectorborne disease have chronic history of vague, often severe illnesses Multiple sclerosis Neuropathies (Guillain-Barre Syndrome) Joint disease (RA) Nephropathies Chronic fatigue syndrome Various immune-mediated disorders (SLE) What can veterinarians do? Get acquainted with your local public health personnel Maybe some are clients? Local physicians sensitive to the presence of vectorborne diseases One Health Initiative – zoonotic diseases Organization that promotes cooperation between various health professions Promote public awareness through public seminars 2 4/27/2012 How often do ticks carry these bad bugs? Ixodes scapularis ticks collected over a fourstate area (IN, ME, PA, WI) 89% of ticks infected with one or more pathogens p g (Anaplasma, ( p Babesia, Borrelia)) 55% of the infected ticks carried a single infectious agent 45% carried two or more infectious agents 37% contained two infectious agents and 8% contained three pathogens (Steiner FE, et al. J Med Entomol 2008. 45(2)289-297) Current project (Florida tick population) Which agents are likely to be involved? Most tick species can transmit more than one agent Ixodes spp. (deer tick): Anaplasma phagocytophilum and Borrelia burgdorferi Amblyomma americanum (Lone star tick): Ehrlichia chaffeensis and E. E ewingii, ewingii B. B lonstari, lonstari R. R rickettsii R. sanguineus (brown dog tick): E. canis, A. platys, R. rickettsii Agents that can be transmitted by multiple arthropod vectors Bartonella spp. Ixodes scapularis (east) and Ixodes pacificus (west) Black-legged tick or deer tick I. scapularis: Eastern coast of the United States as far north as Maine, spreading westward to Iowa Florida to central Texas forms the lower boundary 3 4/27/2012 Important Pathogens Borrelia burgdorferi Lyme disease Anaplasma phagocytophilum Granulocytic anaplasmosis Prevalence of Lyme: Humans Reported in all 48 states in U.S. mainland Alaska and Hawaii Eastern and western coastal states Upper Midwest Distribution coincides with activity of deer tick Prevalence: Canines Reported in all 48 states in U.S. mainland Eastern and western coastal states Upper Midwest Distribution coincides with activity of deer tick 4 4/27/2012 Prevalence of infection with A. phagocytophilum Defining Infection with Anaplasma phagocytophilum Anaplasma phagocytophilum Tick-transmitted, obligate intracellular bacterium Causative agent of granulocytic anaplasmosis Can infect a wide variety of hosts Humans, dogs, cats, horses, ruminants Deer, rodents, and other wildlife (mountain lion, coyote and black bear) 5 4/27/2012 Clinical Signs in Dogs Golden and Labrador retrievers over-represented Three separate studies by Greig 1996, Egenvall 1997 and Beall et al. 2008 (Vector Borne Zoonotic Disease) Breed popularity vs. susceptibility Vague clinical signs of illness Fever, lethargy, anorexia, muscle pain, reluctance to move Lameness and joint pain – inflammatory polyarthritis Indistinguishable from Lyme disease and E. ewingii Meningitis Gastrointestinal signs Respiratory signs (pneumonitis) Morulae in Peripheral Blood or Synovial fluid Microscopic identification of morulae Usually seen during acute phase of the disease (1 to 10 wks PI) 1% - 20% of circulating neutrophils Synovial Fluid Analysis Important in dogs with clinical evidence of joint disease Intracytoplasmic morulae in neutrophils (1% to 10%) 6 4/27/2012 Western Immunblot Assay Horses, dogs, humans and cattle infected with A. phagocytophilum were ere tested Antigen: A. phagocytophilum/ endothelial cell culture 100 50 37 *Dumler et al. 1995 J Clin Microbiol 33:1098-1103 All sera tested reacted with 44 kDa antigen 25 15 Human anti-AP Canine anti-AP SNAP® 4Dx® (IDEXX Laboratories Inc.) Uses synthetic peptides based on a conserved region of the p44 (Msp2) antigen Experimentally, dogs seropositive se opos t ve by 8 days PI,, throughout 340 day trial period Positive control Anaplasma E. canis L Lyme *Alleman et al. 2006, J Vet Intern Med 20:763 Recognized high seropositivity in healthy dogs (some places >40%) Therapy Doxycycline drug of choice Optimal dose and length of therapy not firmly established Current recommendation 5 mg/kg BID, for 30 days Rifampin and levofloxacin in vitro * Maurin et al., 2003, Anitmicrob Agents Chemother, 47:413-415 7 4/27/2012 Response to Therapy Without Complications of Co-Infection Rapid resolution of clinical signs M t dogs Most d hhave significant improvement in 24 to 48 hours There are problems! Are all these animals that are seropositive infected subclinical carriers of a zoonotic disease If animals can be sublclinically infected, can we clear the organism with the current therapy Does Chronic Infection / Chronic Disease Occur? A. ovis can establish chronic infections A. marginale causes productivity losses in chronically infected cattle Persistence despite antimicrobial therapy Reduced weight gain due to chronic, subclinical A. phagocytophilum infection in sheep Anecdotal accounts of clinical disease associated with A. phagocytophilum infection developing in seropositive dogs after initiation of corticosteroid therapy 8 4/27/2012 Human Anaplasmosis Seroprevalence in endemic areas 14.9% of 475 permanent residents tested in Wisconsin Appears to be a common subclinical or mild infection * Bakken et al., Clin. Infect. Ds. 27:1491-1496, 1998 Outcome of treated cases Survey: 85 previously treated cases (102 control) Median interval from time of illness; 24 mo. Patients had lower health status scores Intermittent chills, fever, fatigue, sweats Poorer health status relative to 1 year prior to infection Antibody titers still elevated in one patient Two had elevated AST Post-infectious syndrome Persistent infection * Ramsey et al., Emer. Infect. Ds. 8:398-401, 2002 Three Inoculation Trials Viable A. phagocytophilum organisms given intravenously to dogs Chronic persistent infections developed Chronic, Attempts to clear infection with conventional antimicrobial therapy Evidence of persistent Anaplasma phagocytophilum infection in dogs following doxycycline treatment9 Jeffrey R. Abbott*, Katherine Sayler**, Mellissa Clark* and A. Rick Alleman** *Department of Infectious Diseases and Pathology **Department of Physiological Sciences College of Veterinary Medicine 9 4/27/2012 Inoculations Blood stabilate was used to inoculate one dog (8H12) Virulent field isolate (Baxter), MN The remaining three dogs were infected with stabilate from 8H12 once infection was confirmed Confirmation of infection Serology SNAP® 4Dx® Test (IDEXX Laboratories, Inc.) All seroconverted between days 10–16 DPI CBC Neutropenia < 3000/µl (or decreasing counts) As low as 920/µl Blood and buffy-coat smears Morulae in neutrophils PCR (msp5) Range from 3.7x103 to 1 x 105 copies per 5 µl of whole blood Doxycycline treatment Treatment: Began at 161 days PI All dogs remained seropositive, but PCR-negative, during treatment Trial T i l dosage: d 10 mg/kg /k administrated d i i t t d orally ll every 12 hours for 28 days 10 4/27/2012 Immunosuppression 2 weeks of rest to clear doxycycline Prednisone: 2.2 mg/kg Ad i i Administrated d orally ll Every 12 hours 14 days PCR monitoring of blood Recrudescence PCR: Positive values detected on days 5–6 postprednisone in 3 out of 4 animals Remaining animal, on day 10 postprednisone Verifying the viability of the organisms Three mixed-breed hounds were experimentally inoculated. Inoculum: Postmortem tissues tested via PCR Pancreas from dog 8H05 had highest numbers of bacteria (3.3 x 104 /g tissue) Postprednisone blood (4.3 x 103 /ml) 11 4/27/2012 Inoculation Two dogs Source: Blood Route: IV Volume: 2 ml Bl d 5.0 Blood: 5 0 x 104 bacteria b i One dog Source: Pancreas extract Route: IV Volume: 2 ml Pancreas extract: 3.3 x 103 bacteria Bacteremia Postinfection PCR analysis Freckles(5M67) had neutropenia on day 11 (2,500/µl with 60 bands/µl; normal >3,000/µl) Study Summaries Persistent of infection for over 1 year Seropositive for duration of trials Sporadically PCR positive Doxycycline therapy failed to clear organisms This may not mimic natural infection especially in treatment of acutely infected animals. Value in rapid treatment of infected patients Difficult to identify 12 4/27/2012 Amblyomma americanum Eastern United States, from central and eastern Texas, north into Missouri Spreading east to the coast An aggressive northern expansion of the tick is occurring Reports of LST in Maine Activity of LST Adult activity early as February (warmer climates) Peak activity of adults in spring and summer May and June Most common summer tick in Florida August begins larval activity September begins nymph activity Important Pathogens Ehrlichia ewingii Canine granulocytic ehrlichiosis (CGE) Ehrlichia chaffeensis Human monocytic ehrlichiosis (HME) Ri k tt i rickettsii Rickettsia i k tt ii (RMSF) Breitschwerdt et al. Emerg. Infect. Ds., vol. 17:2011, Primary vector Dermacentor sp. All zoonotic pathogens Borrelia lonestari? – Southern Tick Associated Rash Illness Thus far only in humans 13 4/27/2012 Ehrlichia ewingii Obligate, intracellular bacterium Granulocytes (neutrophils of mammalian host) Causative agent of canine granulocytic ehrlichiosis (CGE) and human granulocytic ehrlichiosis (HGE) Infects dogs, people, goats and deer (reservoir) Prevalence of E. ewingii Can be found anywhere in the geographic boundaries of the LST High seroprevalence in dogs in Missouri, Texas, Arkansas and Tennessee Over 30% of dogs seropositive in MO and TX FL: 2.5% compared to E. canis 0.6% (N.C. FL) Beall, Alleman, Breitschwerdt, Sayler et al. 2012. Parasites and Vectors, 5:29 Causes infection and disease in people Prevalence data lacking Clinical Signs with CGE Nonspecific signs of illness (fever, lethargy, anorexia) Lameness associated with polyarthritis Similar to Lyme and Anaplasmosis Can cause acute disease and/or chronic, persistent infections 14 4/27/2012 Serological Diagnosis of E. ewingii Serological tests currently not available (4Dx SNAP Negative) 4Dx Plus available soon, 2012 One Ehrlichia spp. spot Positive control Anaplasma Ehrlichia Lyme E. canis, E. ewingii, E. chaffeensis Know which tick species! BDT – E. canis LST – E. ewingii and/or E. chaffeensis (zoonotic infections) Example: Prevalence in Arkansas 22 institutions and practices: seroprevalence of Ehrlichia spp.in dogs in US Beall, Alleman, Breitschwerdt et al, 2012 Parasites and Vectors, 5:29 44% dogs tested positive for Ehrlichia sp. 3.6% tested ppositive for E. canis 21.4% tested positive for E. chaffeensis 36.9% tested positive for E. ewingii Does not add up to 44%? 17.9% were co-infected with two or more Almost all co-infections were E. ewingii and E. chaffeensis (L.S.T.) E. chaffeensis Intracellular agents that reside in the monocytes and lymphocytes of infected hosts Causes human monocytic ehrlichiosis (HME) Infection in dogs presumably indistinguishable from E. canis 15 4/27/2012 Prevalence of E. chaffeensis Can be found anywhere in the geographic boundaries of the LST High number or reported cases in humans in Mi Missouri, i A Arkansas k and d Okl Oklahoma h Spreading eastward and northerly Infects people, dogs, primates (lemurs) and several wildlife species including WTD and coyotes 1990 Reported Cases 2007 16 4/27/2012 Clinical Signs of E. chaffeensis Infection in Dogs Waters muddy regarding clinical infections in dogs Suspected similar to E. canis Multisystemic y disease Experimental inoculation fever and thrombocytopenia HME flu-like symptoms Can cause multisystemic disease Neurological signs (meningitis) Mortality (3% immunocompetent; 10% in immunocompromised) Diagnostic Tests for E. chaffee Serological assays IFA for human infections SNAP 3Dx or 4Dx cross-reactive with E. canis How many animals seropositive Positive control f E. for E canis i have h E chaffeensis? E. h ff i ? Anaplasma E. canis Borrelia N.C. FL: 2.1% vs. 0.6%; NC: 5.7% E. chaffee vs. 0.7% E. canis Beall et al, 2012 Parasites and Vectors, 5:29 PCR analysis for species identification Unreliable in persistently infected carriers (Seropositive and clinically normal) Treatment E. ewingii and E. chaffeensis Doxycycline, 5-10 mg/kg BID for 28 days No well established protocol for dose or length of therapy Efficacious in treating clinical disease Are organisms cleared? Anaplasma and Borrelia 17 4/27/2012 Combating tick-borne infections Tick control is the one point where we all agree Simultaneous exposure to multiple tick-borne agents increases the likelihood of developing more severe clinical disease Ixodes – A. phagocytophilum, B. burgdorferi Rhipicephalus – E. canis, A. platys, RMSF, Babesia canis Amblyomma – E. chaffeensis, E. ewingii, RMSF, STARI, PME Multiple arthropod vectors – Bartonella spp. Thank You! Dr. Tony Barbet Dr. Jeff Abbott Katherine Sayler y Dr. Tara Anderson 18