Overcoming Cancer in the 21st Century

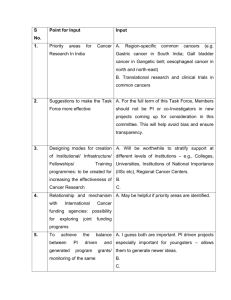

advertisement