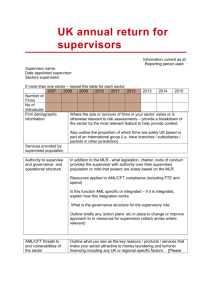

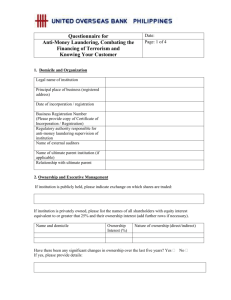

EFFECTIVE SUPERVISION AND ENFORCEMENT BY AML/CFT SUPERVISORS OF THE FINANCIAL SECTOR AND

advertisement