Document 12085905

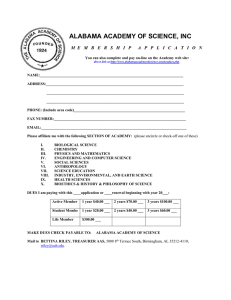

advertisement