JOURNAL for NONPROFIT MANAGEMENT A N :

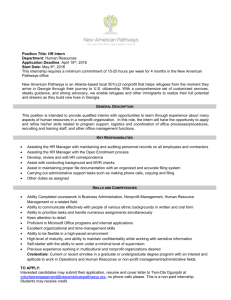

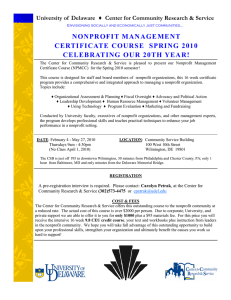

advertisement

ADDING ASSETS TO NEEDS: CREATING A COMMUNITY DATA LANDSCAPE Margaret M. Roudebush, MNO, is the Director of the Center for Research and Scholarship, School of Nursing at Case Western Reserve University. Robert L. Fischer, Ph.D. is a Research Associate Professor and Co-Director of the Center on Urban Poverty & Community Development at the Mandel School of Applied Social Sciences at Case Western Reserve University. Jeffrey L. Brudney, Ph.D. is the Betty and Dan Cameron Family Distinguished Professor of Innovation in the Nonprofit Sector in the Department of Public and International Affairs at the University of North Carolina Wilmington. The nonprofit sector is increasingly focused on using data to inform practice. Social and economic indicators describing the needs of communities are readily available, but data on community assets are often hard to find. This article critically reviews the movement underway to bring together both community indicators of need as well as data on community assets in a common data portal. These portals have emerged largely outside the purview of academic researchers, nonprofit practitioners, philanthropic funders, government and community leaders and service users. Although the initiatives provide powerful frameworks for the collection, display, and analysis of community data, they do not meet all the needs of these highly disparate audiences. This article reviews these new community geographic data systems, discusses the advantages and challenges of launching and sustaining them, and presents suggestions regarding next steps for development in this field. INTRODUCTION A movement is underway in the nonprofit sector that will make geographically-based social and economic indicators along with community asset data more widely usable and available. With such titles as National Neighborhood Indicators Partnership (NNIP), Open Indicators Consortium, and Community Platform, these systems have the potential to support and change decision-making in communities in general and in nonprofits in particular. Yet, the identity and characteristics of these systems are largely unknown to nonprofit scholars, practitioners, leaders, funders, and clients. Moreover, although these systems have captured the attention of some nonprofits, governments, and funders, the challenges and opportunities they confront have not been sufficiently discussed in the scholarly literature. In this article we examine the development of community geographic data systems across the United States, illustrate their potential by reviewing applications operating in various locations, describe the challenges confronting these systems, and make recommendations for further use and expansion. Page 5 2013 JOURNAL for NONPROFIT MANAGEMENT A WEALTH OF DATA The rapid advance of geographic information systems and other information technology; the increasing availability of tax and other records pertaining to nonprofit and public organizations and the broader community; and the development of integrative tools to interlink these rich resources spatially have given practitioners, scholars, and leaders unparalleled access to a wide variety of data organized by geographic location. Many local community data system initiatives are underway working to provide a visual snapshot of the needs of the community through demographic and socioeconomic data together with community asset data provided via nonprofit organization, Internal Revenue Service (IRS), and service provider data. These community geographic mapping systems provide decision-makers with an array of information tied to location that could not have been imagined even a few years ago. In the early 2010s, the technology exists to provide in a single geographic database a large volume of useful information, such as finance and tax, program spending and outputs, emergency services and shared resources, and community needs and resources, all of which can be viewed spatially (Urban Institute, 2011). Tailored to meet the needs and preferences of individual communities, these systems can integrate some or all of these features or modules. The data systems can also be designed to focus on specific “industries” in the community in which nonprofits are actively involved, such as early childhood education, prenatal services, or low income housing. Another advantage of these systems is that they offer the convenience and simplification of providing disparate community data and indicators in a single portal. Consequently, these systems would appear to have great appeal—and use—for a range of community stakeholders. Since the databases may over time incorporate information, community planners can utilize them to depict, understand, and anticipate complex community needs, trends, and growth and decline patterns, as well as experiment with “what-if” scenarios, both geographically and longitudinally. These systems bring together diverse data that can facilitate comprehensive analysis and planning. For researchers, these systems can yield data useful for basic research as well as applied projects that respond directly to immediate circumstances and needs in the community. For government decision-makers, the geographic data systems offer potential for discovering previously hidden community assets that might be brought to bear on public problems, as well as revealing unfortunate shortfalls and voids that ought to be addressed. Examples of hidden assets include such resources as a local food pantry or an after-school program that may be unknown to government (or other) decision makers due to the lack of public funding, but which may be revealed through a GIS (geographic information system) community portal populated by local community data. The systems attempt to compile local investment of nonprofit, public and private organizations, and persistent service needs, in particular service domains, such as unemployment and health care. The availability of better, more comprehensive information can possibly turn discussion, debate, and deliberation from a focus on “government budgeting” for a particular service to a refined emphasis on “community budgeting.” Page 6 2013 JOURNAL for NONPROFIT MANAGEMENT For individual citizens and groups interested in making a difference in their communities, the geographic data systems identify areas where they can be more involved, for example, through donating and volunteering. Conversely, for families and individuals requiring assistance in such areas as nutrition, childcare, job training, and housing these systems can show where and how it might be obtained in the community. For diligent funders, too, these geographic data systems can help to provide guidance in identifying and quantifying community needs, deploying scarce philanthropic resources to meet them, demonstrating the impact of these benefactions thereby “moving the needle” on community conditions. To this listing of stakeholders, we would add nonprofit organizations -- whose financial, tax, and program data typically constitute the backbone of these systems. For nonprofits, which are frequently exhorted to consider the advantages of merger, consolidation, collaboration, shared facilities and “back office” operations with other agencies (Fischer, Coulton, & Vadapalli, 2012), having ready access to information on potential partners is crucial. These systems can provide the impetus to forming collaborations, partnerships, and broader associations among nonprofits (as well as with government agencies and private firms) that may share information, resources, referrals, and the like to rationalize service delivery. Alternatively, for nonprofits committed to making a go of it on their own -- much like their counterparts in business and government -- these systems are equally valuable in understanding the marketplace for particular services and appreciating the dynamics of location and catchment area (Paarlberg & Varda, 2009). These mapping tool platforms also provide a mechanism to collect data on the many nonprofit organizations that fall “under the radar” of IRS reporting requirements by using local nonprofit data such as United Way 2-1-1 information and allowing organizations to register with the community data system and update their information. As Brent Never observes, “By providing a map, we provide legitimacy not only to the entire sector, but especially to those organizations that slip through the formal taxonomies of those who belong in the ‘official’ sector” (2011, p. 187). In this manner, the data systems enable a larger voice for the smaller nonprofit. Smaller nonprofits and faith-based organizations are often at the heart of a local community, providing tailored assistance where needed most. Yet, these nonprofits are usually not required to register with the IRS and may go undetected through the usual data tracking mechanisms. In the local data system, though, faith-based and smaller nonprofits may enter the arena of community service provision. Their activities can then be recognized and made more visible to the larger community, including donors, volunteers and clients. They have an incentive to participate in the local GIS portal to gain partners, allies, funders, and other supporters. Sandi Scannelli, President and Chief Executive Officer of the Community Foundation of Brevard, Florida, reports, the Brevard County Community Platform (“Connect Brevard”) “brought small nonprofits to the table, where they typically don’t have a table” (Urban Institute, 2012). TAKING STOCK OF THE MOVEMENT Over the past 20 years, several initiatives have aimed at increasing access to community-level data. As technological advances have occurred in storing, hosting, and presenting data and Page 7 2013 JOURNAL for NONPROFIT MANAGEMENT 2013 JOURNAL for NONPROFIT MANAGEMENT information electronically, these initiatives have rapidly increased clustering around several goals. Many community data efforts develop organically in response to specific regional needs for data. Several initiatives have emerged to coordinate and support the development of community data by providing an organizational host or forms of self-governance. Table 1 summarizes basic information on major multi-site initiatives. Dating to 1995, these efforts include the National Neighborhood Indicators Partnership, the Open Indicators Consortium, United Way’s 2-1-1, the Urban Institute’s Community Platform, and the Foundation Center’s Philanthropy In/Sight. TABLE 1: EFFORTS TO EXPAND COMMUNITY-LEVEL DATA ON NEEDS ASSETS Member Statement of Initiative Host Launch Sites Objective National Urban Institute 1995 36 To further the Neighborhood development and use of Indicators neighborhood-level Partnership information systems in community-building www.neighborhoo and policymaking. dindicators.org 2-1-1 United Way 1997 In all 50 2-1-1 provides an easy Worldwide/ states way for everyone to http://211us.org/ Alliance of access comprehensive Information & and specialized Referral information and referral Systems services to their (AIRS) community. Open Indicators Consortium/WEA VE Local/regional United Ways and partners University of Massachusetts Lowell 2008 15 To transfer publicly available data into visually compelling and actionable indicators to inform public policy and community-based decision makers. Members of the OIC The John S. and James L. Knight Foundation The Barr Foundation Urban Institute 2010 9 To support transformative community change by enabling publicspirited citizens and nonprofit organizations to work together in new and more effective ways. The Boston Foundation The Charles Stewart Mott Foundation The Kresge Foundation www.openindicato rs.org The Community Platform Initial/ Ongoing Funders The Annie E. Casey Foundation The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation www.urban.org/ce nter/cnp/projects/ Page 8 Figure 1 shows the location of the sites involved in these initiatives (with the exception of 21-1 and Philanthropy In/Sight, both of which exist much more broadly across the United States). All of these community mapping platforms claim to provide an important tool to bridge the information gap between the needs of the community and the areas served by nonprofits. We examine them more closely below. FIGURE 1: LOCATION OF COMMUNITY DATA SITES Tracking Community Conditions A primary goal of these tools has been to create publicly-available (usually web-based) portals housing data on community needs and conditions. These efforts have as a central feature developing indicators of community conditions and making them available at varying levels of spatial geography. The National Neighborhood Indicators Partnership (NNIP) is one of these efforts; it focuses on building local capacity to maintain regional data repositories to further the development and use of neighborhood information systems (Urban Institute, 2012a). NNIP works to make available a range of social, economic, and environmental indicators based on local needs and the organizational capacity and mission of each NNIP partner site. Page 9 2013 JOURNAL for NONPROFIT MANAGEMENT Hosted by the Urban Institute, the National Neighborhood Indicators Partnership includes partner sites in 37 cities. The sites develop indicators related to such topics as births, deaths, crime, health, educational performance, public assistance, and property conditions. Because a key goal of NNIP is democratizing information, a central tenet involves “facilitating the direct practical use of data by city and community leaders, rather than preparing independent research reports.” These sites have adopted as a primary purpose “using information to build the capacities of institutions and residents in distressed urban neighborhoods” (Urban Institute, 2012b). The NNIP has drawn on the network’s collective capacity to expand knowledge in such areas as public health, early childhood and school readiness (Howell, Pettit, Ormond, & Kingsley, 2003; Kingsley & Hendey, 2010). Figure 2 provides an example of a map showing a NNIP community indicator, population change. FIGURE 2: EXAMPLE OF COMMUNITY INDICATOR MAP [Reprinted with permission from Data Driven Detroit] The Open Indicators Consortium (OIC) consists of universities, community organizations, foundations, and regional and state agencies that have come together to promote access and use of high-quality data pertaining to community indicators, services, and government performance. Launched in 2008, the OIC has 16 sites organized in a collaborative network around the development and refinement of “Weave,” an open-source platform. The OIC formed “to support and guide the development of Weave and its application as a high-performance open source data analysis and visualization platform free to all” (Open Indicators Consortium, 2009). Weave enables the user to visualize social indicator data, and the patterns underlying them, nested within Page 10 2013 JOURNAL for NONPROFIT MANAGEMENT and across geographic locations, whether neighborhoods, municipalities, states, regions and nations. Weave is supported by a sliding fee-based membership (www.openindicators.org). Mapping/Accessing Community Assets A related dimension of the movement toward community data platforms has focused on geographic displays of information about community assets and resources. The premise for this approach is that needs assessment also requires identifying and understanding community assets as a central feature of community conditions, and that positive community change emanates from an asset-based approach (Kretzmann & McKnight, 1993). In practical applications, this premise often led to the creation of community maps that revealed not only needs but also key assets such as schools, parks, community gardens, nonprofit organizations, and governmental services. Such maps are useful in informing community planning efforts but are restricted by the detail available on the particular assets, and can quickly become dated. We return to this issue later in our discussion of challenges to these community data systems. In addition to its benefits for community planning, resource mapping is crucial in connecting individuals and families in need with relevant and proximal community resources. Since 1997, the United Way has undertaken a national effort to meet community needs through its 2-1-1 referral systems. Originally, 2-1-1 systems developed as telephone-based referral points for individuals seeking assistance in a wide range of service domains including food, housing, employment, childcare, mental health, substance abuse, and more. The 2-1-1 systems have gradually migrated to the Internet so that they allow individuals to search for referrals in their area with the aid of geographic mapping. Merging Data on Community Conditions and Assets The most recent initiative in the movement toward community data systems is to bring together data on needs and assets in a single, dynamic system. Launched in 2010, the Urban Institute’s Community Platform, is the most notable example. Under development or in operation in over 10 states and counties nationwide, the Community Platform provides sites access to base data on community conditions from the U.S. Census Bureau. This information includes population and social/economic data from the American Community Survey. In addition, sites receive relevant data on nonprofit organizations (i.e., 501c3’s that serve the region encompassed in the community platform, ranging from single cities to multi-county areas, to entire states, based on IRS Form 990 data (Urban Institute, 2011). The data on nonprofit organizations include geographic location, core services, size and history (e.g., year of incorporation). According to the Urban Institute, easily accessible core data allow participating sites to launch a community platform at relatively low cost (an estimated $20,000-40,000 for initial start-up) that provides basic data on community conditions and resources. Sites can also upload locally-available data from nonprofits operating “under the radar” (see above) as well as other information such as crime rates, housing/business foreclosures, and local school and district performance. Individual nonprofit organizations can add data about their programs and services to the sites to enhance the information available. Figure 3 illustrates how a community platform brings together or maps a community need (in this case child poverty rates) with community assets (relevant human service agencies) to address the problem. Page 11 2013 JOURNAL for NONPROFIT MANAGEMENT FIGURE 3: EXAMPLE OF COMMUNITY MAP SHOWING SERVICE LOCATIONS AND NEED INDICATOR [Reprinted with permission from the Louisiana Initiative for Nonprofit & Community Collaboration (LINCC)] Another unique mapping platform, Philanthropy In/Sight, focuses on grant makers and grant recipients data overlaid with demographic and socio-economic data. The Foundation Center leverages its wealth of institutional philanthropy data to create an interactive mapping tool for grant makers, grant seekers, policy makers, researchers, and service providers where they can display giving patterns, analyze foundation impact, or see areas of greatest need. Launched in 2009, users can select from a wide range of customizable options to create maps revealing funding and giving patterns locally, regionally, nationally and globally, and overlay the data with Page 12 2013 JOURNAL for NONPROFIT MANAGEMENT a choice of over 200 demographic, socio-economic and other data sets. The data sets come from a variety of national and international sources including the U.S. Census Bureau, the Social Science Research Council’s American Human Development Project, the United Nations Annual Human Development Report, the Data Catalog of the World Bank and many other government agencies (Foundation Center, 2013). The mapping makes evident areas where funding exists, areas of limited resources and allows a direct comparison to community need. Features allow the user to drill down to reveal detailed information on organizations, funders, and recipients. The Foundation Center customizes the platform for specific community needs or areas of interest, and pledges to update the philanthropic data weekly, and demographic and socio-economic data as it becomes available. While data is available at the local level, by zip code, city or metro area, the system does not allow direct data input by individuals or community organizations. CHALLENGES TO THE MOVEMENT The considerable benefits and advantages of these community geographic data systems notwithstanding, like any other management or research tool, they confront challenges that should be taken into account. Data Access Community data systems are powered and limited by the underlying data available. Though some data are publicly and readily available (e.g., Census Bureau), access to many other types of data must be negotiated at the local and regional levels. Such data often emanate from administrative databases maintained by public entities as well as nonprofit organizations operating in a specific domain. These data pertain to such phenomena as crime, early childhood services, use of public assistance, child mistreatment, court involvement, school performance, and unemployment. Such data often require the negotiation of data use agreements between the data provider and the community data repository and may involve costs associated with providing and processing the data. Negotiations may need to address such topics as data security, protection of human subjects, as well as compliance with relevant protections under federal law (i.e., Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 [HIPAA], Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act of 1974 [FERPA]). Such considerations have implications for the level of data availability (i.e., individual or group); the need for review of these systems by Institutional Review Boards when universities are involved, and the possible requirement of informed consent procedures in obtaining particular individual-level data. Normally, such concerns do not extend to publicly-available data such as those provided through the Community Platform, but they are relevant when sites pursue locally-available data for inclusion in their community geographic data systems. Data Quality Community data systems earn credibility in communities by having data that are accurate, recent, and available for the geographies relevant to users. Typically, better performance on each of these dimensions requires higher burdens placed on the data partners and greater costs associated with managing the data system. More accurate data are achieved by understanding the Page 13 2013 JOURNAL for NONPROFIT MANAGEMENT institutional processes that generated the data, subjecting files to data cleaning procedures, and even suppressing some data of lower reliability. In order to be useful, data provided by local entities must be subjected to routinized approaches to cleaning and verification. Even national data that have been subjected to extensive analysis are fraught with serious weaknesses and errors, such as with IRS Form 990 data (Froelich & Knoepfle, 1996; Froelich, Knoepfle, & Pollak, 2000). The risk of analytic errors becomes even more of a concern when dealing with smaller geographies such as those used in local level data portals. Data systems require continuous updating of data in order to meet the real-time demands of users. More recent data are achieved by having more frequent data extracts from relevant sources and timely processing of these data for inclusion in the community data system. Some data, however, may be available only at specific intervals due to limitations or procedures adopted by various data providers. Geographically relevant data are achieved by having source data that can be geo-coded into a range of geographic boundaries or jurisdictions (for example, municipalities, neighborhoods, city wards or districts, etc.). Yet, street address information may be considered identifying information that is protected by the data provider and may be suppressed prior to transmission. Providing for the accuracy and updating of the data in these portals must be taken into account in system funding. Access to nonprofit organization data raises its own set of challenges. Available literature has certainly benefitted from the accessibility and digitizing of IRS Form 990 data for nonprofit organizations, but this same research has also documented the limitations of these data, which are exacerbated at the local, community level as in the nonprofit geographic data systems described in this study (Froelich & Knoepfle, 1996; Froelich, Knoepfle, & Pollak, 2000; Roudebush & Brudney, 2012). IRS tax data may only capture as little as 10 percent (Smith, 1997) to as much as 75 percent (Salamon & Dewess, 2002) of nonprofit organizations. As in any data-driven system, the results must be limited by the quality of the input data. Data Visualization Community data systems seek to convey information about the scope and scale of community issues and assets and their geographic location. Presenting such information in the most usable fashion remains a distinct challenge for data systems. Often systems allow the creation of tabular information and/or location data in map form. Such output can be very useful but can have limitations as well, particularly for specific users. For example, individuals seeking a childcare facility may be able to use a map to find a nearby provider but may need to search other sources to find detailed information on the program, its quality, and availability in real time. Similarly, a funder of after-school programs may be able to see on the map the programs that exist in an area but may need to use other means to assess whether a shortage or surplus of services is available. Recent developments in the field include strategies to integrate geographic and tabular data so that users can see multiple presentations of data in an interactive fashion. Such data visualization techniques allow users to more intuitively explore the relationship between social conditions and their geographic spread. The Open Indicators Consortium is (re)developing and refining the Weave open-source application around such strategies. Page 14 2013 JOURNAL for NONPROFIT MANAGEMENT Sustainability of Data Systems Even with the facilitation and technical support provided by such entities as the Urban Institute (2011) for one of the geographic data systems, the Community Platform initiative, funders must step forward to underwrite these systems locally. Despite the evident benefits of these systems, as yet only a handful of communities have been able to mobilize the financial commitment (for example, the 12 sites for the Community Platform shown in Figure 1). This situation is aggravated by the fact that these data systems require not only start-up funding but also ongoing, operational support—the kind of “ask” that oftentimes presents a more daunting challenge. Although considerable community interest may accompany (and motivate) the launch and front-end investment in such systems, community data systems require a significant investment of funding and data over their useful life cycle. These systems thrive when data agreements are reliable and provide for regular updates over time. Commitments for data access can be difficult to maintain, especially when the organizations that provide data experience organizational and leadership changes that impact data sharing philosophies. Changes in elected or appointed leadership in public agencies or in CEO/board leadership positions in nonprofit organizations can lead to disruptions or restrictions in data access. Negotiations for data access must consider how to develop arrangements that are reliable and durable over time and resistant to organizational changes. Similarly, the funding required to host and maintain data systems should be developed toward a multiple year horizon. Start-up funding partnerships are crucial, but systems will require sustained core funding over time to support further growth, applications, and functionality of such community data systems. As communities change and evolve, additional funding may be necessary to underwrite specific projects, special analyses and reports, dissemination activities, and system extensions. Technological Divide Although the goals of these systems typically embrace “community building” (Urban Institute, 2011), access to the interactive GIS technology is not distributed evenly throughout the relevant communities of either residents or nonprofit organizations. Those who may need the technology and data most, both individuals and organizations, may encounter greatest obstacles to locating and using them. Portions of the data, or access to the geographical information system itself, may remain proprietary or restricted to a membership group who can best afford it, thus limiting involvement and benefits for the entire community. Another challenge involves building community capacity to use these data systems, which can present a formidable task to those new to the technology. Unless marketing, education, and training are provided—and budgeted— residents, families, and other individuals, as well as charitable and nonprofit organizations, will not know that these resources exist and how to use them effectively. And not all nonprofits will be enthusiastic about having their organizational information posted on a public website that is not controlled by them. Assessing Program Quality: Nonprofit Rating Agencies Ideally, community geographic data systems, such as the ones discussed here, would provide information indicating which nonprofit organizations are best suited to respond to a community Page 15 2013 JOURNAL for NONPROFIT MANAGEMENT need (Never, 2011). Yet, available data on the existence of a nonprofit organization(s) does not convey information about the performance of the nonprofit, who it serves, or how effective it is. In an attempt to make up for this shortcoming and generate high quality data for informed giving, several organizations have been founded with the goal of rating nonprofits and publishing evaluative information about them on the internet. Most of these watchdog organizations rate nonprofits based on financial information from IRS Form 990 and annual reports, and many are limited to large organizations with revenues over $1 million. GuideStar, an online reporting service, covers the broadest range of nonprofit organizations, hosting information on over 1.8 million of them, but it is still limited by a lack of performance or effectiveness measures (GuideStar, 2012). The focus on providing information to aid in donor decision making does not include discussion of geographical areas served, area service competition, duplication of services, or service gaps. The movement toward community geographic data systems aims to provide such information. System designers and funders should endeavor to integrate the evaluative data from the rating agencies to provide a more complete picture of the community nonprofit landscape. CONCLUSIONS Community geographic data systems have emerged in the absence of great scrutiny from practitioners and academic researchers. Accordingly, in this article we have described the different systems that encompass the movement toward community geographic data systems, illustrated their considerable advantages, and elaborated the serious challenges that must be confronted to realize their full potential. In our view, these systems can be a highly useful tool to promote positive community change provided they are used and embraced broadly across relevant stakeholders in the community. We believe that the joint mapping of socio-economic needs alongside nonprofit resources can help to promote knowledge, engage community discussion, and enable more efficient use of resources as gaps as well as duplication in services are more easily identified. The design of community geographic data systems will benefit from increased attention to the interests of various stakeholders, as well as funding arrangements that provide for both start-up and ongoing developments and changes. For communities to realize the potential advantages of such data systems that will allow for dynamic analysis of both needs and assets of a community, plans must be built on a sustainable model. In addition to providing high quality data in a timely fashion, a marketing, and education plan must be put in place to encourage and train public, private and nonprofit leaders and individuals to use and support the system. Plans must include the participation of data providers along with data users. The design and implementation process merits the kind of systematic scrutiny we have endeavored to present in this article. Given its distinctive history and service-delivery patterns, each interested community will likely approach creation and implementation of a community geographic data system somewhat differently. The lack of standardized measures threatens the usefulness of the data beyond the local community. Nevertheless, we anticipate that the reliance on the same established sources for most data, such as the U.S. Census Bureau and the Internal Revenue Service, will help to Page 16 2013 JOURNAL for NONPROFIT MANAGEMENT standardize data collection for use by nonprofit managers for benchmarking and scholars for comparative research. Because local governments and philanthropic funders might have the most to gain from these systems with respect to increasing their ability to make informed decisions, they might reasonably be expected to take a leading role in this process. As pointed out at the outset of this article, the emergence of community geographic data systems has outpaced academic attention to them -- despite their importance for both government and nonprofit practitioners and academic researchers. We have been able to provide the current state of the art, which combines disparate threads and developments, but many questions and issues lie beyond the scope of our inquiry as well as available data and published research. First, although the community portals vary by host site, we do not know the advantages and disadvantages of their different features. Second, at this writing we have not been able to obtain information on the operation of these systems, including the crucial questions of data accuracy and updating. Third, research has not yet assembled evaluations from the various stakeholders that will be key to the further development and improvement of these community data systems. With such new information, we could begin to offer informed advice concerning whether the potential benefits of these data portals warrant some form of federal or state reporting mandate to participate in data collection. We are at work investigating these questions and hope that our continuing study will inform academic research, community practice, and public policy REFERENCES Fischer, R. L., Vadapalli, D., & Coulton, C. (in press). Merge ahead, increase speed: Bringing human services nonprofits together to explore restructuring. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly. Froelich, K. A., & Knoepfle T. W. (1996). Internal revenue service 990 Data: Fact or fiction? Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 25(1), 40-52. Froelich, K. A., Knoepfle, T. W., & Pollak, T. H. (2000). Financial measures in nonprofit organization research: Comparing IRS 990 return and audited financial statement data. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 29, 232-254. Foundation Center. (2013) About Philanthropy In/Sight. Retrieved June 20, 2013 from http://philanthropyinsight.org/Help/About.aspx 2013. GuideStar. Retrieved December 10, 2012 from http://www.guidestar.org/. Howell, E. M., Pettit, K. L. S., Ormond, B. A., & Kingsley, G. T. (2003). Using the national neighborhood indicators partnership to improve public health. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice, 9(3), 235-242. Page 17 2013 JOURNAL for NONPROFIT MANAGEMENT Kingsley, G. T., & Hendey, L. (2010). Using data to promote collaboration in local school readiness systems. Washington: The Urban Institute. Kretzmann, J. P., & McKnight, J. L. (1993). Building communities from the inside out: A path toward finding and mobilizing a community's assets. Chicago, IL: Northwestern University for Urban Affairs and Policy Research. Never, B. (2011). The case for better maps of social service provision: Using the Holy Cross dispute to illustrate more effective mapping. Voluntas, 22, 174-188. Open Indicators Consortium. (2009). Retrieved October 10, 2012 from http://www.openindicators.org/portal. Paarlberg, L. E., & Varda, D. M. (2009). Community carrying capacity: A network perspective. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 38(4), 597-613. Roudebush, M. M., & Brudney, J. L. (2012). Making policy without parameters: Obtaining data on the nonprofit sector in a local community. Nonprofit Policy Forum, 3(1), 1-23. Salamon, L. M., & Dewees, S. (2002). In search of the nonprofit sector. American Behavioral Scientist, 45, 1716-1740. Saunders, R. C. & Heflinger, C. A. (2004). Integrating data from multiple public sources: Opportunities and challenges for evaluators. Evaluation, 10(3), 349-365. Smith, D. H. (1997). The rest of the nonprofit sector: Grassroots associations as the dark matter ignored in prevailing “flat earth” maps of the sector. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 26(2), 114-131. Urban Institute. (2011). The community platform: Engagement, analysis, and leadership tools. Washington: Center on Nonprofits and Philanthropy. Urban Institute. (2012a). About NNIP. Retrieved December 10, 2012 from http://www.neighborhoodindicators.org/about-nnip. Urban Institute. (2012b). NNIP Concept. Retrieved October 10, 2012 from http://www.neighborhoodindicators.org/about-nnip/nnip-concept. Page 18 2013 JOURNAL for NONPROFIT MANAGEMENT