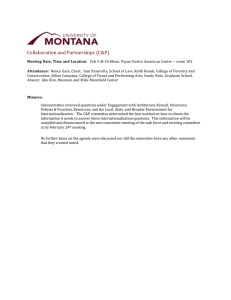

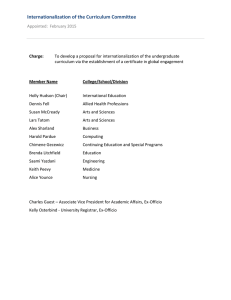

Globalism and the University of Saskatchewan: at the University of Saskatchewan

advertisement